Bacon’s Better Philadelphia, circa 1947

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

Sixty years ago this month, a team of visionary planners, architects and civic activists presented Philadelphians with a high-tech glimpse of what their city could one day be – if they were willing to plan for the future.

In 1947, Philadelphia was both booming economically and brimming with post-war optimism. Federal redevelopment money was plentiful. City Council had five years earlier created a new, stronger Planning Commission that had a technical staff and a mandate to create guidelines for growth.

But “most Philadelphians didn’t know what planning was,” said Greg Heller, president of the Ed Bacon Foundation.

Bacon was part of a who’s-who team that wanted to change that. He, architects Oskar Stonorov and Louis Kahn and civic leaders such as Walter Phillips and Edward Hopkinson wanted not only to get city residents excited about planning, but convince them it was worth their tax dollars.

“Their primary goal was to bring legitimacy to the city’s new planning commission,” Heller said at an event held Tuesday night to celebrate the Better Philadelphia Exhibit, which opened on two floors of Gimbel’s Department Store in September 1947.

Hopkinson raised the $340,000 it took to build the exhibit, plus additional money that paid for billboards, newspaper and radio ads. In one month, 385,000 people flocked to the exhibit.

These days, many more Philadelphians understand planning. In fact, neighborhood associations have become their own community’s advocates and, at times, vocal critics of what gets built where.

Still, Heller and the other planners and architects who led last night’s discussion think it might be time for another big planning exhibition to get Philadelphian’s thinking about their city’s future.

Many are already talking about redeveloping the city’s waterfront. Penn Praxis recently unveiled a vision that calls for extending the Center City street grid out to the Delaware River. Those who attended planning meetings this past summer often came to talk about what they didn’t want – the two proposed casinos. But they also passionately talked about what they wanted: access to the water. Green space. A healthy port and small-scale commercial and residential development.

And Philadelphians recently voted to overhaul the city’s zoning code. A Commission charged with updating and simplifying the code, as well as removing any inconsistencies, began meeting last month.

“At the moment, I feel a swing back in the direction of planning,” said architectural historian David Brownlee. “People are fed up with private interests dictating what happens in a peace meal way.”

In the 1940s, the movement toward planning was fueled by the post-war feeling that anything could happen. The current climate is more about a determination that some of what is happening will stop.

People today don’t want as much top-down guidance from city planning, Heller said – many like the large influence of neighborhood associations – but they do want the city to take a leadership role and set stronger development guidelines.

The 1947 exhibit, which forecast the Philadelphia of 1982, assumed most Philadelphians needed much more than that.

One section explained that city planning was really not so different from the kind of planning regular people do in their lives. It showed a sports team planning their next moves, a young couple planning to marry, even a squirrel planning to save nuts for the winter. The only person shown not planning for the future was a bum.

At the time, Heller said, there was a real need for such associations, because critics often linked city planning to communism – especially when the plans included government-funded, affordable housing.

Bacon knew this well, said Heller, who is writing his biography. Bacon had previously worked in Flint, Michigan, and had essentially been run out of town because people there thought he was a communist.

Better Philadelphia “reaffirmed the need for planning through economic, capitalist reasons,” Heller said.

Bacon came up with the concept for one section – The Time and Space Machine – while aboard a Navy ship. A series of layered glass plates were lit one by one to show the city throughout the centuries, showing Philadelphia’s physical footprint, the mode of transportation most commonly used to get around it, and prominent buildings from the time.

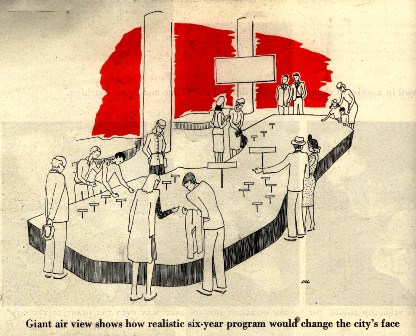

But the most enduring part of the exhibit was a model of the city with buildings and roads, green spaces and industrial places, and neighborhoods shown in great detail.

Giant hands would flip sections of the model that depicted the undesirable to reveal the better things that could be had instead; residential neighborhoods clogged with traffic congestion and cramped housing became parks with airy, modern homes. A portion of the exhibit remained at the Civic Center until 1976. Since then, few have seen any of the still smaller section that remains, but many remember it – including about 30 of the 100 or so people in attendance Tuesday night.

The model was not based on any budgets, only aspiration and imaginations. Still, “Most ideas in the model of Center City came to pass in one way or another,” said James Kise, consulting principal of the Kise Straw & Koldner planning and architecture firm.

There was a small concept of Penn’s Landing. Independence Mall was represented, as were Bacon’s Society Hill greenways. Philadelphia was presented as the economic center of the region. And at a time when many cities were knocking down the old to make room for the new, Better Philadelphia suggested keeping much of what already existed.

Heller noted that much of what happened required the effort and money of the private sector. “It was not just the Planning Commission and federal dollars,” he said. “Look at Penn Center – the Pennsylvania Railroad owned it, and here is Ed Bacon telling them what to do. Market East was done by a private developer and Society Hill required lots of private individuals.”

Kise said public/private efforts will also be needed to create the Philadelphia of the future. One of the reasons he likes the idea of extending the street grid to the Delaware River is that it would break a large swath of land into smaller areas where that could happen. “The city has been waiting on a single developer to take it all on, and that’s not going to happen,” he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.