Mixing uses on the Delaware

Ed Hille/Old and new on the waterfront

Oct. 19

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

Philadelphians want to bring more people to the river’s edge, but they also want to protect the natural shoreline.

They want to improve water quality and support industry.

They want to shop, eat and live along the Delaware, but not at the cost of the working port, which they want to grow.

When it comes to this river, they want it all.

Penn Treaty Park

Striking a balance between demands that at times seem contradictory can be done, but not easily, say local experts and those from cities which are farther along in waterfront development than Philadelphia.

Peter Steinbrueck

There’s no magic wand that will make everyone agree what should go where, said Seattle City Councilman Peter Steinbrueck – reaching consensus takes a lot of talking, a lot of planning, and sometimes, tough decisions that literally shape the city’s future. Seattle recently completed a waterfront revitalization plan, and Steinbrueck, a former practicing architect, is chair of the Urban Development and Planning Committee. “There are going to be conflicts, and there are going to be disagreements – that’s inevitable,” he said.

In Philadelphia, the talking and planning is happening on several fronts – and not without conflict:

In partnership with the City, Penn Praxis has spent a year holding public meetings with residents, business people and political leaders to gather goals for the Central Delaware Waterfront – the area between Oregon and Allegheny avenues.

The resulting vision – a key component of which is extending existing streets down to the river – will be released to the public at the Convention Center on Nov. 14. But when Praxis Director Harris Steinberg gave a synopsis to the Philadelphia City Planning Commission this week, it was clear the vision would face scrutiny.

Following Steinberg’s presentation, a development attorney said the street grid embraced by those who came to the visioning meetings for its human scale would drastically reduce the value of his client’s property. A representative of an organization that promotes industry in the city said the plan called for too much open space and public access and that residential properties should not be placed where industry might grow in the future.

Change and conflict

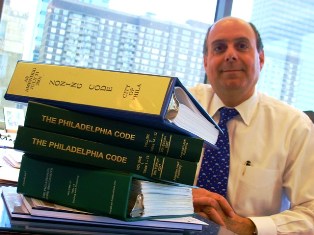

Zoning attorney Peter Kelsen

A city-wide referendum earlier this year led to the formation of the Zoning Code Commission, a group charged with updating and revising the city’s zoning code.

But unlike many cities, Philadelphia lacks a comprehensive plan – an outline for what type of development and land use occurs in each part of a city that shapes all development decisions. And some have questioned whether such a document is needed to properly update the zoning code.

SugarHouse model

Then there is perhaps the biggest riverfront conflict of all: Building two casinos on the river’s edge.

The state legislature, at the urging of Gov. Rendell, voted the gaming in. Yet the legislators in whose districts the casinos would be built have been less than enthusiastic. Rep. Michael O’Brien has repeatedly said he’s not anti-gambling. “If they wanted table games, I’d support it,” he said in a recent interview. But he doesn’t like the location, and neither do his constituents: many of the neighborhood associations representing river wards are united against Foxwoods and SugarHouse building at their current locations.

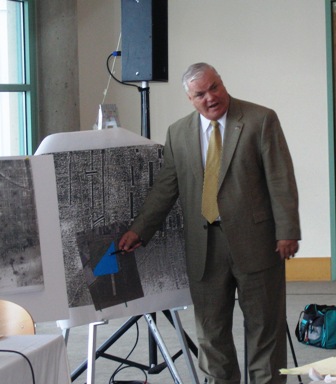

State Rep. Bill Keller explaining and defining riparian land

The casinos want the right to build on riverbed lands, but O’Brien says he won’t sponsor legislation to grant them those riparian rights without a community benefits agreement. (In Pennsylvania, Riparian rights can only be granted by an act of the legislature, and by long standing tradition, only the legislator who represents the district that contains the land in question submits the legislation)

Most of the community organizations aren’t negotiating with the casinos. Fishtown Neighbors Association spokesman Herb Shallcross says there’s nothing to say until SugarHouse moves elsewhere.

Room for competing interests

As fractious as the discussion has been so far, Philadelphia’s lucky, said architect and urban planner Ken Greenberg, the former director of urban design and planning for the city of Toronto.

“The waterfronts on the Schuylkill and Delaware are so extensive, you’ve got places for everything,” said Greenberg, who has also worked on waterfront renewal in New York, St. Paul, San Juan and elsewhere. Just the Central Delaware section from Allegheny to Oregon Avenues contains 1,100 acres between I-95 and the water’s edge.

Some here think the easiest and most logical route is to set different goals for the two rivers.

ZBA chair David Auspitz

For example, David Auspitz, chairman of Philadelphia’s Zoning Board of Appeals, member of the Zoning Code Commission and chairman of The Bainbridge Group, Inc., sees the Delaware as the hustling-and-bustling river where industry, commerce and residential development should take precedent and the Schuylkill as a bike-and-picnic place where nature rules.

Auspitz wants to keep and improve the parks that exist along the Delaware, such as Penn Treaty. And he thinks a public walkway along the entire length is a must. He sees it as a place for jogging, walking and rollerblading. He imagines outdoor cafes, retail and restaurants – from TGI Fridays to fine dining.

For the Delaware “just to have fallow land for green space, it’s not the place for it,” Auspitz said.

Our industrial past

Old Delaware River piers

Old industrial sites that are unused or underused make up a significant portion of Philadelphia’s waterfront – about 1,000 acres along the Delaware alone, and hundreds more along the Schuylkill.

What can reasonably be done with the pieces deemed no longer needed for industry hinges in part on the industry that used to be there – as in, how much damage it did to the land?

Land reclaimed for residential development has to meet higher environmental standards than land used for commercial development – where people shop or work but don’t sleep, said John Haak, a senior planner for the city of Philadelphia who works with industrial lands.

If another industry moves in – or if a parking area is created – standards are lower, he said.

Philadelphia City Planning Commission Executive Director Janice Woodcock, who also chairs the Zoning Code Commission, said it makes much more sense to turn former industrial sites into homes or businesses than to try to re-naturalize them. Sites such as old piers would be more appropriate as natural areas. (For instance, Hudson River Park has reestablished Striper fishing habitats by leaving old pilings in place.) See Flora and Fauna of the Delaware.

“There are areas where there are old piers, there are shallow, tidal parts of the river. If you clean those up, the fish come back. There’s so much benefit and it’s so much less expensive – why tackle something that will cost five times as much?” she asks.

No matter what planners decide should come of those areas, change won’t happen if current owners don’t sell or re-develop.

Some keep property because they hope to use it again some day, Woodcock said, while others are waiting to see what kind of rezoning the city might have in mind, because the zoning helps determine property value, and the land may one day be worth more.

The Ikea site’s value increased 4 or 5 times when it was rezoned from industrial to commercial, she said.

A different future beckons

No one ever questioned what should be done with the waterfront in Philadelphia or any city when the shorelines were the bustling economic centers.

But waterfront renewal has become a right-of-passage for many places with industrial pasts,

Many of the world’s cities sprung up along a river, a lake, or an ocean because that body of water fostered industry and commerce.

“Railways, port facilities, warehousing, manufacturing, tank farms – that industrial infrastructure was responsibly for the prosperity cities enjoyed for a long period of time,” said Greenberg.

But in the latter part of the 20th Century, much of that industry and the jobs it brought have dried up. Obsolete infrastructure lies unused or underused. And cities are finding themselves in need of both a new economic engine and new uses for sizable swaths of land, Greenberg said.

Revisioning old ore piers

“Many cities are quite literally reinventing themselves on the edge of waterfronts,” he said. “The entire future of a city, in many cases, has to do with how well they take advantage of this opportunity.”

But how do you decide what to do where?

“You start with public access to the waterfront as a driver,” said Seattle’s Steinbrueck. “The waterfront is a resource, it should be seen as an amenity for the entire city and region. You don’t want to unduly limit it by turning it all over to private developers,” he said.

But “whatever plan that emerges also needs to be an economic plan. It can’t all be open space and no people living in the area – that’s going to create desolation.”

Access to the waterfront – even in front of privately owned businesses and residences – isn’t just about a democratic attitude, Greenberg said. It’s also good economics.

Hudson River Park promenade in New York

“Battery Park City in New York has a great promenade along the water,” he said. “If the only people who got to enjoy it were the few lucky condo owners right on the water … the value of that frontage to New York as a whole would be much less. But because it’s easy to get to the promenade in many places, the whole neighborhood, and much of Lower Manhattan, increases in value.”

New York has preserved natural areas that are open to the public, at least in part. Others – including the Jamaica Bay nature preserve – are off limits.

“Along with other uses, there needs to be a focus on keeping industry where it still is – that’s important to people,” said Howard Slatkin, the Deputy Director of Strategic Planning for New York City who was project manager for the 2005 Greenpoint-Williamsburg rezoning that affected more than two miles of East River waterfront in Brooklyn.

Haak, the Philadelphia planner who works with industrial lands, said there are some areas that will likely stay industrial even if their current use ends. For example, the 100-acre Conrail site.

“There’s a limited supply of waterfront sites … that have railroad, good highway access, and are not sensitive to sensitive residential or commercial uses. By that standard, from a city-wide planning standpoint, it needs to be held in your industrial reserve.”

Philadelphia needs a plan

New York City has a comprehensive waterfront plan that establishes what functions it wants from its waterfront, including natural areas, public areas, working areas and areas that need to be redeveloped.

Woodcock said she’d like a city-wide comprehensive plan here, too. But there’s no money for that – and so far, not enough political will, she said. But a precursory step is underway.

“We are working this fall on policy papers that are laying the foundation,” she said.

Everyone loves a plan, Greenberg says.

“The enormous benefit of doing that, for investors, is it takes out a lot of the uncertainty,” he said. “They know where they can go, and they know who their neighbors are likely to be.”

The policy papers are being created by Planning Commission staff, and each paper will make recommendations about a particular kind of land use, including green space, residential, commercial, transportation and industrial. Future forecasts – such as what kinds of industry are likely to grow here and what the housing needs are – will be part of the planning.

Skirmishes along the way to new riverfronts are welcomed by Woodcock.

South Philadelphia principle session

“It’s OK that this guy says a place should be green, and this guy wants housing, and this guy wants industry,” she said.

“It’s that tension that brings people to the discussion.”

Delaware Riverkeeper Maya van Rossum is fine with seeking a balance among desires for uses for the river – as long as the river’s needs get as much weight on the scale as the others.

“If your priority is houses, when you put trees and shrubs along the river, it gives back and restores the river, but it also enhances the value of the homes,” she said. “It cools the homes, it gives a beautiful view.”

Use porous surfaces to build trails and parking lots, she said. Consider vegetative rooftops.

“Don’t just say, ‘this was a brownfield’ and take 100 percent to serve the people’s needs, regardless of the impact on the river,” she said.

Kellie Patrick is a former Philadelphia Inquirer reporter. Contact her at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.