Philadelphia doesn’t need crystal ball

July 30

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

Cities and regions that will be globally competitive in the future must change the way they develop now, said a group of national and local experts who spoke at Wednesday night’s discussion of urban infrastructure at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

About 450 people braved a steamy summer night to hear Alex Krieger, a founding principal of Chan Krieger Sieniewicz and professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and Trent Lethco, associate principal of ARUP Inc., talk about the best urban development practices they have seen in cities across the country and world. The audience was also there to hear reactions to those concepts and ideas from Philadelphia officials who oversee relevant departments: Deputy Mayor for Transportation and Utilities, Rina Cutler; Commissioner of the Department of Parks and Recreation, Michael DiBerardinis; and Acting Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development and Planning Commission Executive Director, Alan Greenberger.

While the discussion traveled from China to Savannah, from stackable electric cars to parks literally created with paint and unused space at an intersection, several themes ran throughout the program, which was presented by the Penn Institute for Urban Research, PennDesign, PennPraxis, Next American City and the Academy of Natural Sciences.

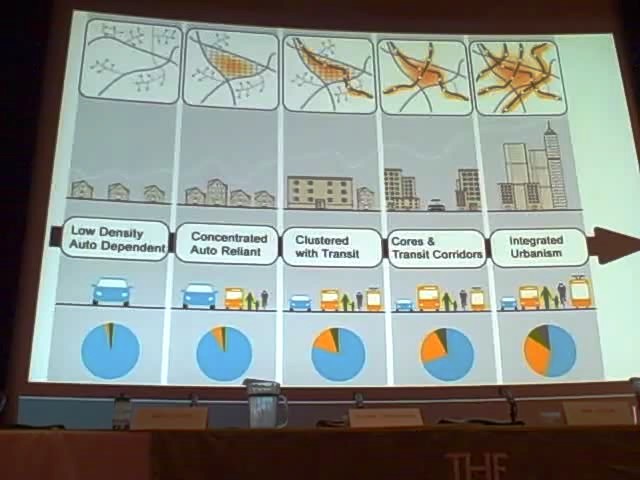

– In the future, resources will be scarce and more expensive. Usable land will be more precious. Future development should take place in dense, urban settings.

– These hubs of homes and jobs should be navigable by means other than the automobile. People will take transit, walk or bike if it is safe and convenient for them to do so.

– The hubs should also be linked to each other.

– Developing in this concentrated way means there will be more land for green space, both for people and wildlife.

Marilyn Jordan Taylor, Dean of the Penn School of Design, set the stage for the speakers and moderated the discussion. She hit early on another big theme: The pro-urban attitude in Washington is something new, and something that might not happen again, so cities should act now. For example, she said, the office of Housing and Urban Development and the Department of Transportation are now operating with the goals of creating more transportation choices, equitable and affordable housing, enhancing economic competitiveness and valuing communities and neighborhoods. They are looking for ways to get the most out of any money invested, she said.

“This is the moment for cities. This is the moment, especially for cities like Philadelphia,” she said.

Wednesday night’s event capped off a three-day workshop, which was not open to the public, that was designed to generate ideas that may help Philadelphia get its fair share of federal dollars. The workshop results will be presented to city leaders and the public in the fall.

Taylor showed a series of maps of this region superimposed with dots representing jobs and population. There are definite areas of concentration, but also lonely dots, scattered in areas that have few transportation options that aren’t tied to the automobile.

“We’re an urban species,” Krieger said during his presentation. And yes, we do sprawl. But, as Taylor’s maps illustrated, we also build in concentration. Even the latter consists of eight or nine “megalopolitan” areas, he said. Philadelphia is in the middle of one of them. “This is where the future of our nation resides,” Krieger said, especially if we want a future that is more focused on environmental stewardship than how we did business during the last century.

“To achieve the proper balance of infrastructure and natural systems, you have to become a lot more regionally cooperative,” he said, saying he hoped everyone present would “convince the couple of million people around you that this is what you should be doing.”

True regional cooperation is hard – particularly in places like Pennsylvania with its many, many municipalities. But regional planning has been done in the past, he said – just look at the highway system.

Krieger pointed to Portland’s green belt, and showed how regional planning had created a dense, urban core surrounded by a ring of greener spaces. Lexington, Ky., did the same sort of planning years ago – to make sure there would be grasslands for the thoroughbred industry, he said.

He has worked in the city of Shenyang, which, like other Chinese cities, must absorb the flood of residents moving in from the countryside. Shenyang has 10 million people, he said, but they are planning to grow to 20 million. The city wanted to develop an area that is predominantly farmland. People in China like to compare their cities to Manhattan, Krieger said. “So we said, look, we’ll give you five Manhattans” each containing two million people. Krieger showed a map of Shenyang with five Manhattan shapes laid across it from the core of the existing city outward. Each one was separated with corridors of natural spaces and farmland. These side-by-side swaths of dense urban development adjacent to green areas would create environments that were easier and more pleasant for humans while allowing space for nature, too, he said.

Lethco pointed out that the messy sprawl is our fault – we created government policies during and after World War II that made it happen. Highways were built, and then, after the war, cheap housing and GI subsistence money helped returning soldiers buy in the suburbs. The good news, he said, is “if we are just as intentional and just as proactive, we can see our cities change.”

Lethco is a transportation guy – “my topic is hot right now,” he told the audience. The demand for mass transit is increasing, he said. And last summer’s gas prices were only a hint of what’s to come. The average family of four spent more than $2,800 on gas in 2005, and, in 2007, the annual cost of traffic congestion was $87.2 billion and 4.2 billion hours in lost productivity.

At the same time, he said, the current economic crisis has produced service cuts that are coming on top of two decades of “chronic disinvestment” in infrastructure.

What should regions be doing?

“We like to take the USDA food pyramid and turn it on its head. You know, if we’re going to think about transportation, people really need to come first.” Lethco showed an inverted pyramid where the top, broadest level represented pedestrians, and the following, ever-shrinking levels were cyclists, public transportation, deliveries and finally, at the narrow tip, private cars.

“If we can get it right for people and bicyclists, then we can get everything else right.” It’s much harder to retrofit roads with bike lanes and sidewalks after the fact, he said. And if you give people the right infrastructure – so that they enjoy walking or bike riding and feel safe doing it – they will do it.

“Cities that are thinking today about how they link what their (comprehensive) plans say about land use with what their transportation plans are saying about corridors and streets, and can really articulate about how we can get sustainable streets, multiple mobility outcomes, and see returns in terms of development, those cities will be most effective as we look at the reauthorization of our transportation funding bills,” Lethco said.

Some cities already get this, Lethco said. He consciously chose East Coast examples: Toronto for its regional framework. Arlington, Va., for changing growth through transit-oriented development, and New York City for working with resources it already has.

Toronto has created “a network city of cores and corridors” – dense areas that are connected to each other via transit, he said. The entire waterfront is being re-imagined and Toronto is now looking to make individual buildings as green as possible.

Arlington has been focusing on transit-oriented development for years. In the 1970s, that county updated a land use plan from the early 1960s to include the goals of preserving existing neighborhoods, encouraging mixed use development, and concentrating that development around train stations, Lethco said. Further refinement in the 1980s and ‘90s called for high density development along the transit corridors, more growth within ¼ mile of each station. And included goals for open space and “concentrating development there to protect historic, single family residential areas,” he said.

At first, Arlington needed to provide developers with incentives to build in their transit corridor – but no more. These days, demand – and profitability – are high.

Arlington, has seen a reduction in car ownership, and, between 1991-2006, Metro ridership doubled, Lethco said. There are more high-paying jobs within 1/3 mile of stations, because companies believe employees like it.

New York, through PlaNYC, has greatly increased the number of bike lanes and green space. With little more than tables and some paint, it has created mini-park refuges at points where streets intersect. And new development – such as the new World Trade Center buildings – will be dense and encourage walking, biking and mass-transit oriented commuting.

After the presentations, Taylor asked questions of the panel. How will Philadelphia make the most of the current administration’s willingness to invest in urban areas, she asked Greenberger.

Greenberger said that last week, he participated in a Brookings Institute round table focusing on severely distressed cities. “That’s not our designation,” he said. “But at the same time, about a quarter of Philadelphia does fit the definition of severely distressed.” The good news, he said, is that the panel was assembled because the office of Housing and Urban Development wants to know “what it can do to target support to cities with these characteristics,” which include vacant land and a high level of poverty.

How can Philadelphia get some of that help HUD wants to give? Greenberger said that he sees “real elements of economic opportunity” in this city, but they are isolated from each other. Greenberger referred to Krieger’s talk of patches of development and connecting corridors. “It doesn’t take much to connect the dots, but our dots still are not connected,” he said. “We have single assets, not a network of assets.”

Taylor asked DiBerardinis what could be done with some of Philadelphia’s vacant land from a parks and recreation standpoint. He said he was trying to determine now how his department and its facilities could best serve both residents and visitors – and that includes looking at how equitably the facilities are spread and how well they are connected to public transit and regional assets. “How does vacant land serve those interests, and how do we bring open space and public land to underserved communities.”

In response to a question about what additional infrastructure is the priority after existing infrastructure is fixed, Cutler laughed. “Ok. No pressure there!” She said it would take approximately $35 billion over the next 25 years to repair and update all the roads, streets, bridges, and other infrastructure in the region.

Right now, there’s “a financial dilemma” because there are “a lot of good ideas but not a lot of good funding sources for them. Some folks who have projects moving forward, or designed, are going to have to give those projects up,” she said.

Cutler said she will have no fewer than 12 projects hitting her desk seeking letters of support to get some of the federal dollars earmarked for regional projects, and deciding which of them to write is going to be brutal. A decision will need to be made about whether a multi-use trail is more important than transit or new transit oriented development. “We will need to make decisions to try to figure out the biggest bang for the buck, because there is only a buck,” she said. To write all 12 letters would mean “working against myself” she said.

Several attendees had questions for the panelists, including one gentleman who asked the three Philadelphians what one physical change or policy they would wish for.

“A dedicated funding source for acquiring, developing and maintaining public space,” DiBerardinis said.

“A city-wide commitment to progressive development and a willingness to develop,” said Greenberger.

Cutler said she needed two wishes: “On the policy side, I’d like to see the language, and spirit of the language we hear in D.C. trickle down to the regional and local level,” she said. And a physical change? “A world-class transit system.”

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.