Zoning czars, public to hear outcome of PIDC study

If the zoning code is where city planning’s rubber meets the road, a recent review of Philadelphia’s industrial sector is where the paper meets the process.

At its monthly meeting scheduled for Wednesday (June 9), the Zoning Code Commission will hear from John Grady, vice president of real estate services for the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp., which completed its “Industrial Land Use and Market Study” earlier this year.

PIDC’s study is part of a national trend within perceived “post-industrial” American cities, said Laura Wolf-Powers, assistant professor of city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania, while attending the American Planning Association’s annual conference in New Orleans in April.

“Economic development professionals and elected officials are taking stock of land use patterns that developed under ancient zoning ordinances,” Wolf-Powers said. “They are figuring out how industrial land use relates to fiscal policy, and to employment policy.”

Some 20 percent of Philadelphia’s citizens are employed in the industrial sector, the PIDC finds, amounting to more than 100,000 jobs.

The jobs are only a part of what Mark Alan Hughes, Mayor Nutter’s first sustainability chief and the architect of the city’s Greenworks plan, calls Philly’s big “upside opportunity” – a chance to restore, to fill in, homes and coffee shops and maybe even factories long shuttered. They are sustainability’s internal organs. And “sustainability,” when you think of infill development, has as much to do with the rusty old industrial sector as it does with any shiny new green technology or urban farming schemes.

Meanwhile, the promises inherent in industrial sites – environmental remediation and re-use of brownfields once thought to be lost forever, green buildings, green jobs – seem to be shaking the rust from the sector.

Think of it as the ultimate in recycling. The word itself, “industrial,” much like “infrastructure,” is a bland, dry term that is verging on the retro chic. Unlike the technical revolution of the past 20 years, where words have been invented – bent from nouns into verbs and back again (“meetup,” “Google”) – the green movement has reclaimed the plain language of the past.

“Gray water” means “green water” if re-used or treated right. “Brownfields” inspire colorful optimism, via opportunism. On rooftops across the land, there is a creeping wonderment amid the creeping ivy. Black tar and shingles are making way for white tiles and foam, gleaming solar panels and tomato planters. And “factory” and “manufacturing” are gaining traction as words that describe re-discovered classics, like a 50-year-old set of heavy Lionel trains found in a corner of the attic.

By reinvigorating the local distribution of living wage employment to blue- and “pink-collar” earners, it is possible to create an interdependency in cities like Philadelphia and Baltimore (and even Detroit, given half a chance). The lifeblood of sustainability is opportunity, and where there are already existing footprints – veritable templates from decades gone by – cities thought to be “not what they once were” are positioned to be the hubs of green, opportunistic industry. Aquariums and thousands of new condos and sidewalk cafes are a great start, but they are not going to be much help up on Hunting Park Avenue in Juniata, or down on Lindbergh Boulevard in Southwest Philly.

“I tell ya, I can’t think of a better place to be,” said Garry Fadula, vice president of operations at PTR Baler & Compactor Co., located on East Ontario Street in Kensington. “I’ve seen so many companies move out of the city and go to the suburbs, taking up green, open areas, basically abandoning the infrastructure that was already there. And what did they get for it? Very high taxes, employees who live in $300,000 houses, and need to pay that mortgage. The public transportation isn’t there – that’s another green item. About 50 percent of our shop employees take public transportation.”

Fadula, who has been with the century-old PTR firm for 36 years, was on a roll. “What can you say? We’re three blocks from I-95,” he said, bordering on the incredulous. “This city, actually, has been really, really nice to work with, my whole career. When I call, they help us. Why? They want us to stay. We’re a great tax base.”

Fadula is under no illusions about Philadelphia’s economy. But he says he thinks the exodus of jobs witnessed in the ’70s and ’80s has pretty much stopped. “Why? Because the suburbs don’t want you anymore,” he said. “They want their green space. The code enforcements out there are enough to drive you crazy. There are fees for everything. I really feel like I could do an advertisement for the city – they really go out of their way to help you stay here.”

Mayor Nutter? Meet Garry Fadula, your new best friend.

Re-using, re-inventing

One place growing under the new paradigm of “industrial mixed use” is the Navy Yard in South Philadelphia, a resource so vast and rich in re-imagination, yet so overlooked, it is seemingly hiding in plain sight to your average Philadelphian. It is literally the same size as Center City, with an amazing amount of infrastructure left in place when the former Navy base and shipyard closed a decade ago.

“It’s hard to import Tastykakes from China,” said Grady, who oversees the immense mixed-use redevelopment of the Navy Yard for the city.

Over nine years, PIDC says it has stewarded some $400 million in private investment to create about 8,000 jobs, including positions at the Aker Philadelphia Shipyard, Urban Outfitters, Tasty Baking, Ben Franklin Technology Partnership and 80 other private companies. During 2009, Implementation of the Navy Yard Master Plan during 2009 focused on more than $100 million of infrastructure, the underpinning for an anticipated $1 billion of addition al private development in the coming handful of years.

Grady can become like a kid at Christmas when driving around the old base, the Delaware River a constant presence to the east and south. Tasty Baking recently opened a brand new baking and distribution facility there, to great fanfare. To him, the place has it all over the suburbs, in spades.

“Amenities become really important. People want to have that connection to the water,” Grady said. “They want to have food and beverage, they want to have conveniences. The ability to track and generate those kinds of conveniences is really what distinguishes the suburban corporate office park experience from the opportunity you get with an urban park.”

The late Willard Rouse, the legendary developer who built Liberty Place and founded Liberty Property Trust (which is now entrusted with the nuts and bolts redevelopment of the Navy Yard), would likely have approved of Grady’s message. Rouse was responsible for many of those suburban office parks. But in early 1999, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Great Valley Corporate Center, a pioneering office park he developed off Route 202 in Malvern, Pa., Rouse lamented the commuter experience found in such leafy locales.

“People get in their cars … and generally that’s a pretty isolated experience,” Rouse said. “You go from there to the office and see the same people, generally, everyday… And you go home at night in your one-passenger automobile … the interaction and the stimulation of your brain is fairly limited. There is a social infrastructure that’s got to be created, that’s missing.”

So mixed-use is a social good as well as an economic incentive.

“There’s really an opportunity for mixing uses that are really compatible with one another,” said Gary Jastrzab, deputy executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission. “You’re not going to have apartments next to a smelting foundry or a steel plant – but there are certain compatibilities where residential and commercial, and some kinds of industrial, are able to exist side by side.”

Jastrzab said the Planning Commission has a special study underway for the Hunting Park area, site of the former Budd Co. plant and large swaths of decaying industrial infrastructure. He said the commission’s community planning division, which started the study last year, would like to have it wrapped up by the end of calendar year 2010.

“We’ve seen the market in Northern Liberties and parts of Kensington where those parts of neighborhoods are in transition,” Jastrzab went on. “The Crane Arts building in Kensington is a great example of a large industrial building converted to artists’ work spaces and other kinds of mixed uses. It’s making use of those spaces where you have multi-story – most industrial [companies] want one floor.”

Out of the shadows

The commission’s study will be one of at least three concerning industrial re-use within the next six months or so.

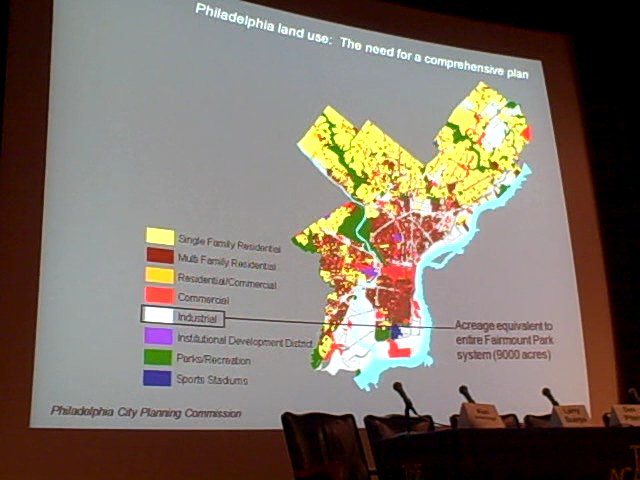

The big one, May’s release of the PIDC’s ambitious industrial overview, looks at a 20 percent snapshot of Philly’s industrial parcels over 15 districts zoned for the sector.

The Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority is also undertaking a more general vacant land study, which it hopes will result in increased property taxes and a “more transparent and accessible system” to spur private investment. It is part of a plan that includes a broker sales pilot program. Hundreds of properties have already been moved out of the RDA’s backlog.

“PIDC’s vacant land study is more of a physical study,” said Terry Gillen, executive director of the RDA and senior economic adviser to Mayor Nutter. “Our study is a systems study – how it gets into the status of being vacant, and how we can get it out.”

That entails speaking to the city departments of Law, Revenue and Public Property, among others. “We’re really focusing on the legal and revenue systems that lead to vacant land,” Gillen said.

Roger Nielsen, president and owner of Abbey Color Inc., a maker of dyes for the bio-chemical industry on East Tioga Street in West Kensington, will be glad to hear that.

“Right next door we have two lots,” Neilsen said in an interview at his plant. “We should reclaim them. An industrial building came down, and an industrial building should go back up. I don’t need more houses.”

One of the key points coming out of the PIDC land use study is that industrial land has been bid up in price over the past decade or more, while the residential real estate bubble grew and then burst. But retail commercial property went up dramatically, too.

Neilsen said that makes sense to him.

“I’ve seen more retail up here, and a lot of money go into old industrial lots, after they tore the buildings down,” he said. “If you look just down Aramingo Avenue, you’ve had a Lowe’s come in, a Home Depot. You’ve had a plethora of the self-storage places. But not the kind of jobs that I would like, that’s for sure.”

Gillen said the Vacant Property Review Committee (VPRC; within the city’s Office of Housing) is responsible for transferring the city’s vacant property to people who want to buy land from the city. Her office has been working with the VPRC and the Office of Public Property “to go through the backlog in VPRC to try to make some decisions on how to get the properties back into use. Some of them are awaiting policy decisions, and there’s a whole range of other decisions – it’s a management challenge.”

There’s the big picture that says over the past 30 or 40 years, PIDC has acquired, improved and sold perhaps 2,500 acres of industrial land around the city, Grady said. That’s largely concentrated in Northeast and Southwest Philadelphia.

“We have a couple hundred acres of that land left in our inventory,” Grady mentioned. “If we want to continue to encourage industrial land use – and that doesn’t mean smokestack manufacturing – part of this study is to identify what is really the industrial economy in Philadelphia.”

So, ready for something you don’t hear everyday?

“The property taxes are a steal,” said Fadula, of PTR. “They are a bargain here. [Taxes are] no reason to leave. You’ve got a million and a half people in the city, so this work force, when it snows, they come to work. You don’t have to worry about driving to work, or digging your car out of the driveway. And when you start adding it all up, there’s no service that I might need that can’t be here within five to ten minutes.”

Plumbing, electrical, hydraulics – Fadula’s got a guy for all of them, right around the corner.

“Where are you going to find that in the suburbs? That convenience?”

Note to Select Greater Philadelphia, and the folks at the Chamber of Commerce: Meet Garry Fadula, your new best friend.

Contact the reporter at ThomasWalsh1@gmail.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.