Why play spaces need to get created, and how we do it

“When we stop playing, we start dying,” clinical psychiatrist Stuart Brown has famously said. Nancy Goldenberg, a Parks & Recreation commissioner and vice president for planning at the Center City District, invoked the quote to begin her look at the history of the playground at yesterday’s “Kid-Friendly City: Planning for Play Places.”

The program was presented by the Pennsylvania Chapter of the American Planning Association’s Southeast Section and was sponsored by Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, PennDesign, the William Penn Foundation, Temple University, and others. It took place at the DVRPC offices, directly across the street from what has to be one of the nation’s most successful new urban play areas, Franklin Square.

Goldenberg’s short overview came midway into the morning, but her summary — which touched on everything from Darwin to immigration to Teddy Roosevelt — served to nicely remind the dozen or so attendees about the power of play.

And it brought home all the more the power of the project that had been introduced at the day’s first presentation: the re-do of the Greenfield School’s playground in Center City. Although the K-8 school serves many affluent residents, some 70 percent of its students come from elsewhere in the city. And, more than 50 percent of students — who hail from 40 zip codes — participate in the school lunch program, added presenter Lisa Armstrong, an architect whose involvement was solely as a parent volunteer.

Armstrong described how what became known as “Greening Greenfield” first got underway when the city contacted the school and offered to bestow a $100,000 grant if it could come up with a way to green its grounds and include an environmental education component while doing so.

Working with the Community Design Collaborative as well as a task force comprised of representatives from agencies like the Center City District, the Philadelphia Water Department, and the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, Greenfield developed a plan to get rid of two unsightly elements that had removed much of the element of play from the grounds: a huge dumpster, and an area that had become a parking lot for some two dozen cars.

When the school was ready to present the plan — it incorporated the planting of shade trees, the removal of asphalt, and other sustainable elements — the city stalled the effort by announcing that the $100,000 was no longer available and any talk of improvements were to be placed on hold.

Momentarily deflated, the group soon decided to pursue the project independently and then to gift it to the school district, relayed Armstrong. A community visioning program followed, with the participation of alumni, alumni parents, teachers, students, and other community stakeholders — and things got accomplished.

Ultimately, the redesign of the playground fell to SMP Architects, along with Viridian Landscape Architects and Meliora Environmental Design. Last summer, the west end of the school grounds were completed, and construction is now underway on the east end.

The redesign includes a rain garden, an agricultural zone, 26 new trees, and a playground with permeable surfaces. Eventually, a green roof will be added. “Everything we’ve put in tries to do double duty,” Armstrong said.

A recycling program at the school has significantly reduced waste and eliminated the need for the dumpster; while a firm reminder from a regional superintendent that the playground is for kids and not cars has gotten rid of the parking issues. (Teachers have always had access to a nearby parking lot.)

Each of the project’s two phases have been pegged at about $230,000 for construction costs alone. They’re funded with everything from kids’ penny drives to federal grants from the U.S. Bureau of Fish and Wildlife. The playground is open to all members of the community, Armstrong said.

The hope is for the project to serve as a model for other city schoolyards, and to that end the process has been extensively documented and even videotaped by students who received training from WHYY. “Meanwhile, play is happening, water is being collected, and indigenous gardens are growing,” said Armstrong.

And, if all goes according to plan, the same will be said after the forthcoming re-design of Sister Cities Park is completed next May. Goldenberg introduced this project after presenting her overview of playground history which, she said, has led us to where we are now: the “McDonalization” of playgrounds.

But the brightly-colored, one-piece, molded structures that make up today’s spaces are not solely to blame for the failure of the field, she continued. “Design is not the only reason playgrounds have become dull,” Goldenberg said, before citing the loss of natural environments, the loss of unstructured time for kids, and the increase of risk-averse, “helicoptering” parents.

She then moved specifically into the context of Sister Cities Park, which is surrounded by institutions that host two million annual visitors. Its redesign is part of the CCD’s greater improvement efforts on the Benjamin Parkway intended to correct the balance between autos and pedestrians, and to ease access to those institutions. The plan also includes the creation of “an activity every minute,” she added; those activities can range from reading a sign to eating lunch at a cafe.

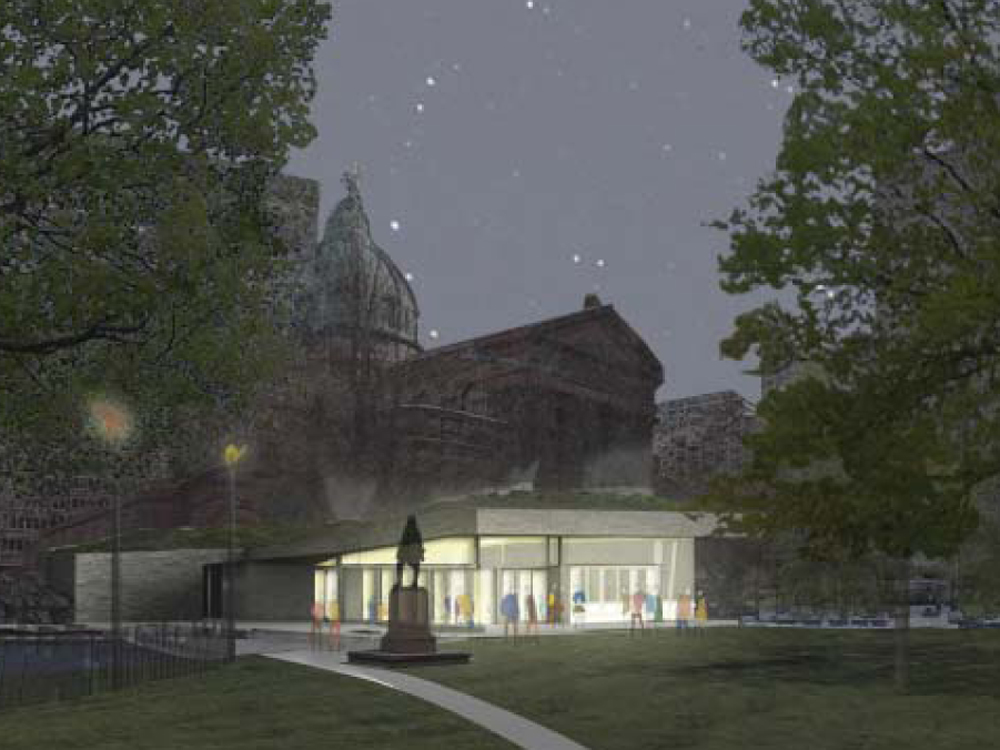

Activating Sister Cities Park is part of that mission, then, and Philadelphia-based landscape architect Bryan Hanes (along with local design firm Digsau) has the gig. He presented a look at the problems of the two-acre park — which occupies the ill-used and neglected northeastern corner of Logan Square. After brainstorming with stakeholders, he said, the new design incorporates visually playful and kinetic elements, a mixture of active and contemplative spaces for a variety of users (including children), and a spatial connection with the Basilica and the Swann Fountain.

The budget for construction — which includes a signature water element, a cafe and dining terrace, and a “discovery” garden with a model boat pond — stands at $4.6 million, he said.

The program finished with a presentation by Stuart Dash, director of community planning for Cambridge, MA, on “Healthy Parks and Playgrounds.”

Contact the reporter at jgreco@planphilly.com

Check out her new online magazine, TheCityTraveler at thecitytraveler.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.