Special Report: Vacant land, focused plans

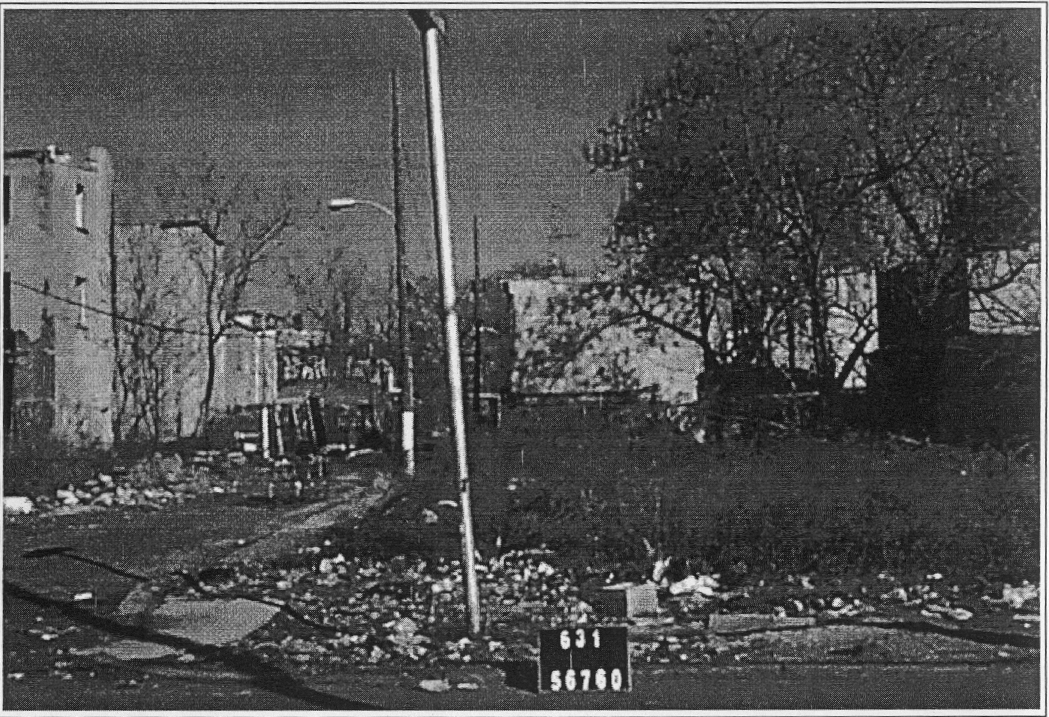

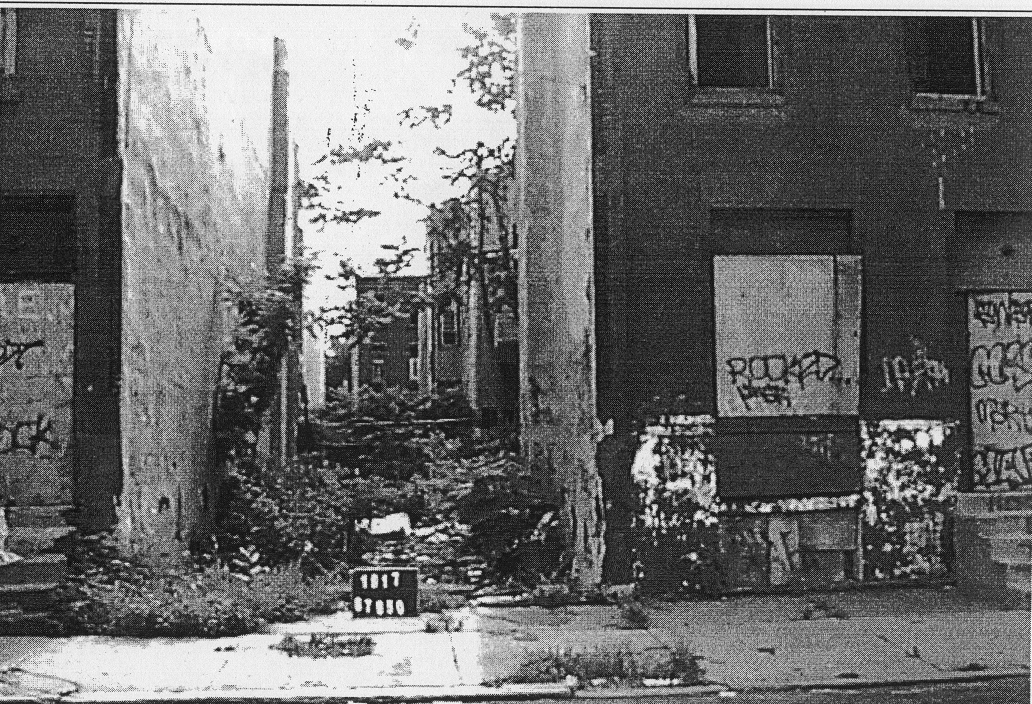

In the 1990s, the best that could be said of Eastern North Philadelphia was that there was almost nothing there.

Acres of vacant land stretched in all directions, the empty expanse broken up only by a scattering of rundown row homes. The few remaining residents lived largely in dilapidated public housing rental units while those who could fled for other sections of the city where there were more amenities, more buildings and more neighbors.

It was a landscape desolate enough to startle even the most calloused observers of urban decay, “a true no man’s land,” said Rick Sauer, executive director of the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations.

A 1998 city survey of the area found 2,173 empty buildings and vacant lots in the neighborhood. The abandoned properties outnumbered occupied structures by more than two-to-one.

In the coming months, PlanPhilly will publish a series of reports on the Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha and its role in Eastern North Philadelphia’s revival.

Among other topics, the stories will cover the experiences of the area’s residents, the politics and racial dynamics of urban recovery, the design and architecture of low-income developments, and the massive investment of taxpayer funds that enabled the neighborhood’s transformation.

The writing, video and photography that comprise this series is made possible by a grant from the William Penn Foundation.

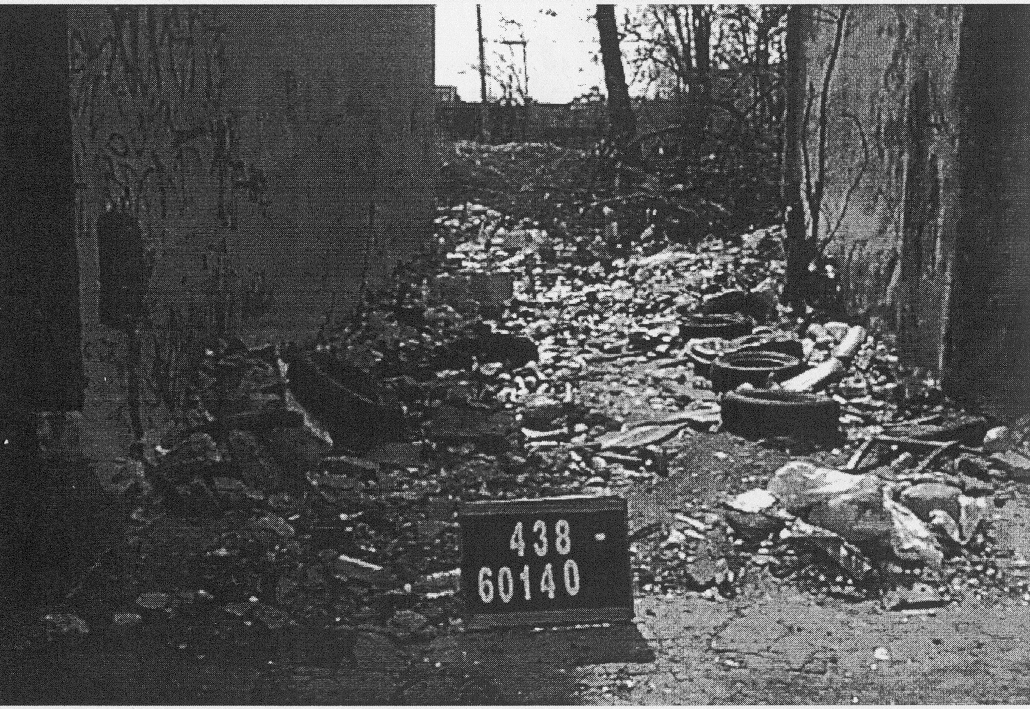

But in the surplus of vacant land – filled with ditched appliances, wrecked cars and 12-foot high weeds – one local organization saw tremendous opportunity.

The group was Asociación de Puertorriqueños en Marcha, or APM, and its leaders had figured out that no one – not the city, and certainly not private developers – would be riding to Eastern North Philadelphia’s rescue.

“I don’t know if we were just dismissed or not seen. We were invisible to folks. It was a neighborhood that no one really saw,” said Nilda Ruiz, APM’s executive director. “So we said let’s get up and do it.”

At the time, APM’s plan seemed almost absurdly optimistic.

The organization would construct hundreds of units of housing. It would create over 1,000 jobs. It would put a suburban style shopping center at the devastated corner of Berks and Germantown Avenues.

Its goal, really, was to build a healthy, functional, fully-serviced neighborhood in a section of the city that had seemingly no hope of attracting private development.

Against all odds, and all expectations, APM succeeded. Eastern North Philadelphia has been brought back from the dead, and there are real reasons to expect that a full recovery is not only possible, but likely.

A video introduction to Eastern North Philadelphia and this series. Story continues below…

Since 1990, APM alone has built 359 housing units, and has secured funding for another 160. The improbable shopping center, dubbed Borinquen Plaza (in honor of Puerto Rico), now hosts a large supermarket and a TruMark credit union. There are entire blocks lined with new pitched-roof townhomes and lavishly tended gardens that would blend with ease into suburban Montgomery County.

And more is coming.

Work is already underway on a LEED-certified 13-unit development that will become one of the city’s few examples of cutting-edge architecture aimed at low and moderate income residents.

Construction will begin next year on APM’s largest project yet, a 160 unit mixed-use complex bordering Temple University.

Next year, APM and a major New York-based development firm called the Jonathan Rose Cos. will break ground on a $40 million-plus mixed use project covering over half a city block adjacent to the Temple University regional rail station. The complex has the potential to improve the neighborhood’s physical connection to the university, bridging the imposing barrier created by an elevated SEPTA viaduct that divides Temple from the APM area.

Including those new developments, APM – through a mix of city, state and federal grants and loans and foundation assistance – has generated over $100 million in new development in the area.

The full extent of Eastern North Philadelphia’s transformation is detailed in a new study of the area released today by the Fels Institute of Government at the University of Pennsylvania.

In 1998, John Kromer – then head of OHCD – led a city survey of abandoned properties in a series of Philadelphia neighborhoods, including the area served by APM. Today, Kromer has released a second survey of APM’s neighborhood through the Fels Institute of Government at Penn. The survey examines what has become of the vacant lots he found in 1998; tracks property values and sales over time; and highlights the efforts of non-profits and city agencies active in the area, with a particular focus on APM’s work. This PlanPhilly report leans heavily on Kromer’s findings.

The lead author, John Kromer, is the former head of the city’s Office of Housing and Community Development, and a figure who was instrumental in helping APM get its redevelopment ambitions off the ground during the Rendell administration.

His report is based on two detailed surveys of vacant land in the area, the first conducted from 1998-2000, and a second count made over the past year. Together, the surveys offer a compelling before-and-after picture of Eastern North Philadelphia.

- Of the 2,173 abandoned properties that plagued the neighborhood in 1998, only 687 remain.

- 475 lots have been redeveloped, mostly by APM, and filled with new housing or commercial ventures.

- 908 vacant lots have been cleaned up, and converted into well-tended publicly-accessible grassy plots, private side-yards or parking lots. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society – in concert with APM – maintains 285 of those lots, planting trees on the land and mowing the lawns regularly, an effort that, incredibly, has turned Eastern North Philadelphia into one of the city’s greenest sections.

- Property values are soaring. In the 1990s, the median sales prices of homes in the neighborhood was just $3,000, less than half of what area properties fetched in the 1970s. In the past decade, the median sales price has jumped to $24,500.

The real-world impact of those impressive numbers is plain when walking through the neighborhood today.

Kromer recalled that Eastern North Philadelphia was a “quiet, kind of scary” place when he was first introduced it.

“At this point, you can get much more of a sense of community. There’s activity going on on the streets, families with children enjoying the area, shopping in the supermarket, people going to work and traveling to and from school,” said Kromer.

“So there’s a sense of life and vitality there that was not very much in evidence when I first visited the community.”

Old men play dominoes on plastic chairs and tables in PHS cleared lots. Freshly painted murals abound. Residents grill food in their yards and spray their kids with hoses while watering the lawn.

Such commonplace city scenes might seem like scant evidence of redevelopment. But for the wasteland that was Eastern North Philadelphia, the return of normal street life signals enormous progress.

Vacant lots that are maintained by PHS feature an open wood fence with openings narrow enough to prevent unwanted dumping.

“The transformation over the years has been dramatic. You walk there now, and there are parts that look almost suburbanite. It’s hard to believe it was just blocks and blocks of vacant land up there only a few years ago,” Sauer said.

To be sure, Eastern North Philadelphia has a long way to go.

With the exception of the Borinquen Plaza, the Germantown Avenue commercial corridor remains blighted and largely empty. Crime rates are higher than the city average, and serious social problems remain. And while the current inventory of 687 unimproved vacant lots and abandoned buildings is far smaller than it once was, the eyesores still account for about 20 percent of all the parcels in the neighborhood.

Nonetheless, what APM has accomplished so far is remarkable, and all the more so because it has been done, until now, with virtually no private-sector investment.

That last point is unusual in Philadelphia, where neighborhood recovery is often synonymous with gentrification.

But unlike Northern Liberties or Southwest Center City, Eastern North Philadelphia’s recovery is not a gentrification story. Rather, it’s a rare example of revitalization attained through a combination of non-profit led planning and taxpayer-funded investments.

“I view that neighborhood as one of the city’s great success stories,” said Deborah McColloch, who eventually succeeded Kromer as head of the city’s Office of Housing and Community Development.

Kromer agrees. And he suggests that other distressed neighborhoods, in Philadelphia and elsewhere, have a lot to learn from the APM experience.

“Yes, there was a lot of public investment. But government programs have not been as successful in other areas,” said Kromer, who is the author of Fixing Broken Cities, a book about urban redevelopment strategies.

So, Kromer said, policy makers ought to be asking: how did APM do it?

An interactive graphic detailing the changes in Eastern North Philadelphia. Story continues below…

The APM Formula

Careful and patient planning has been key to APM’s success. The organization impressed Kromer and other city officials with its first comprehensive strategy for the neighborhood back in 1994. Since then, APM has doggedly stuck to its vision for Eastern North Philadelphia, demonstrating a discipline that some non-profit developers lack.

Located just east of Temple University, the neighborhood served by APM is an often overlooked section of the city squeezed between Fairhill to the north and Ludlow to the south. The organization’s strategic development plan stretches from 4th Street in the east to 9th Street in the west. North to south it reaches from York Street to Berks Street, with a smaller section doglegging further south to Jefferson Street.

“There’s really no other neighborhood in the city where you can find the same level of consistency,” said Kromer, who wanted to study the area partly to see the results that kind of patience would yield. “There are other excellent CDCs, but none of them have been as consistent in carrying out a plan that was designed and approved over a decade ago.”

Another key for APM has been its pitch-perfect approach to Philadelphia politics. So far, the organization has managed to work the system, without being consumed or corrupted by it.

“They’re smart about doing what they have to do politically, but they are not totally dependent on the political system,” said Terry Gillen, executive director of the Redevelopment Authority. “Some CDCs come to rely on one or two politicians, and use them as a crutch. My sense is that APM hasn’t fallen into that trap.”

Instead, APM has developed partnerships with other redevelopment groups, such as the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society and its vacant lot stabilization programs. That and other partnerships have helped the neighborhood tap into non-APM funding streams, increasing the overall investment in Eastern North Philadelphia.

Another APM strength is the professional experience of its development staff, which is led by Rose Gray. A veteran of both a private sector development company and the city’s department of Licenses and Inspections, Gray was the lead administrator for fewer than three development-related municipal boards in her 10 years on the city payroll.

“Rose knows how to make the system work. She knows who to call. She’s familiar with the process. When there’s a challenge, she knows how to deal with them,” Sauer said, speaking to APM’s ability to navigate Philadelphia’s challenging system for acquiring vacant land.

Development savvy alone does not account for APM’s successes, however. Kromer contends the organization’s long history as a social service provider was crucial to achieving community buy-in for APM’s redevelopment plans.

For all of APM’s work in Eastern North Philadelphia, another group, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, has arguably had a more dramatic visual impact on the neighborhood.

Best known for producing the annual Philadelphia Flower Show, PHS also runs a pair of city-funded vacant lot cleanup programs that have reclaimed 11,000 million square feet of abandoned land across the city, including 285 parcels in the APM neighborhood.

The converted lots in Eastern North Philadelphia now resemble well-mowed grassy yards, enhanced by a few tree plantings and enclosed by thigh-high wooden fences.

It is a deliberately simple aesthetic, designed to provide an “attractive open space that can be created and maintained on a production basis,” said Bob Grossman, director of the PHS vacant land program.

Work crews contract with PHS to mow the lawns and clear out any litter that piles up (which is not a lot, at least in the APM area). But the organization does not own the land itself. Some of the plots belong to the city, but many are titled to individuals or companies that have long since abandoned the parcels.

The redevelopment value of the cleaned and greened lots is clear.

“To build housing, a CDC has to attract residents into the area. And who wants to live across the street from a vacant lot that may harbor drug activity or prostitution?” asked Grossman. “When we came in these lots were full of trailers, toilets, cars. They were horrendous. Nobody is going to buy a new house across the street from an overgrown lot filled with rats.”

Just as important, the attractive plots make it easier – for community members, APM, and would-be builders – to imagine new developments taking form on the empty land.

Despite its success, the program’s funding was cut by 25 percent last year, as the city struggled through its budget crisis. The cuts have forced PHS to reduce its maintenance schedule.

“Having an organization that is comfortable in both spheres, real estate development and human capital development, is really important. The CDCs that have been most successful during the past decade all have that quality,” Kromer said, citing Project H.O.M.E and the People’s Emergency Center.

One tangible example of the link between APM’s social service programs and its development wing can be seen in the housing counseling it has long offered to low and moderate income homebuyers.

That experience was invaluable when APM was selecting families to sell its newly developed homes to. The organization picked applicants who were deemed likely to maintain their homes and avoid missed payments. And so far, not one of APM’s home buyers has been forced into foreclosure, despite the economic climate and the nationwide foreclosure crisis.

Javier Rivera was among those to buy an APM-built home, and he is a good example of the kind of working class residents the area is now able to attract.

He moved to Philadelphia from New York to 2001, following his job with Ready, Willing & Able, a non-profit organization benefitting the homeless.

At first, Rivera and his family rented a tiny but pricey apartment in Northern Liberties. One day, Rivera ran into a Latino policeman, and when he asked the cop where he might find more affordable housing, the officer said, “buddy, you need to get on 5th Street and head up.”

Those directions led Rivera to Eastern North Philadelphia.

When he first toured the area, Rivera was skeptical.

“Crime was rampant, the litter was a problem, and people frankly didn’t take care of their homes,” he said.

But Rivera also saw the work APM had done, and he figured the neighborhood might turn around. So he took a chance, and moved his family into one of the non-profit’s rental units.

The apartment worked out well enough, but Rivera wanted badly to own a home. He was working two jobs, saving money, so he applied for a home in APM’s new Pradera development.

Rivera was rejected.

But he was persistent.

He went through an APM housing counseling program, and attended classes on avoiding predatory lending. Over time, his credit score improved, and so did his income.

“There wasn’t a workshop I missed,” he said. “I was determined to get this home.”

In 2007, he finally did. APM sold him a 1,600 square foot Pradera townhome for $100,000, making permanent residents out of a solid working class family.

“I did a lot of homework before trying to buy this home,” Rivera said. “I did it because I saw the neighborhood had potential.”

Eastern North Philadelphia’s Collapse

In the early 1980s, Eastern North Philadelphia seemed to have no potential at all.

As a young project manager for the city’s Office of Housing and Community Development, John Komer recalls standing on the 13th floor of the City Hall annex and watching as the North Philadelphia skyline lit up. The fireworks came from a blaze at the shuttered Hardwick & Magee carpet factory at 6th and Lehigh Avenue

“I found that very illustrative of what was happening to North Philadelphia as a whole,” Kromer said. “The economy was globalizing and the manufacturing firms that had been the backbone of this area moved away or went out of business, leaving behind empty buildings and eventually empty houses as the factory workers left to follow the jobs.”

In the first half of the 20th century, Eastern North Philadelphia had plenty of jobs.

Rowhomes stood cheek-to-jowl with small-scale manufacturers and warehouses throughout the APM neighborhood. The nearby American Street industrial corridor was arguably the capital of Philadelphia’s manufacturing might, crowded with textile factories, tanneries and meat-packing plants.

The John B. Stetson Hat Manufactory – a sprawling 20-building complex at 4th and Montgomery – employed as many as 3,500 workers at its 1920s peak, before it closed down in the 1950s.

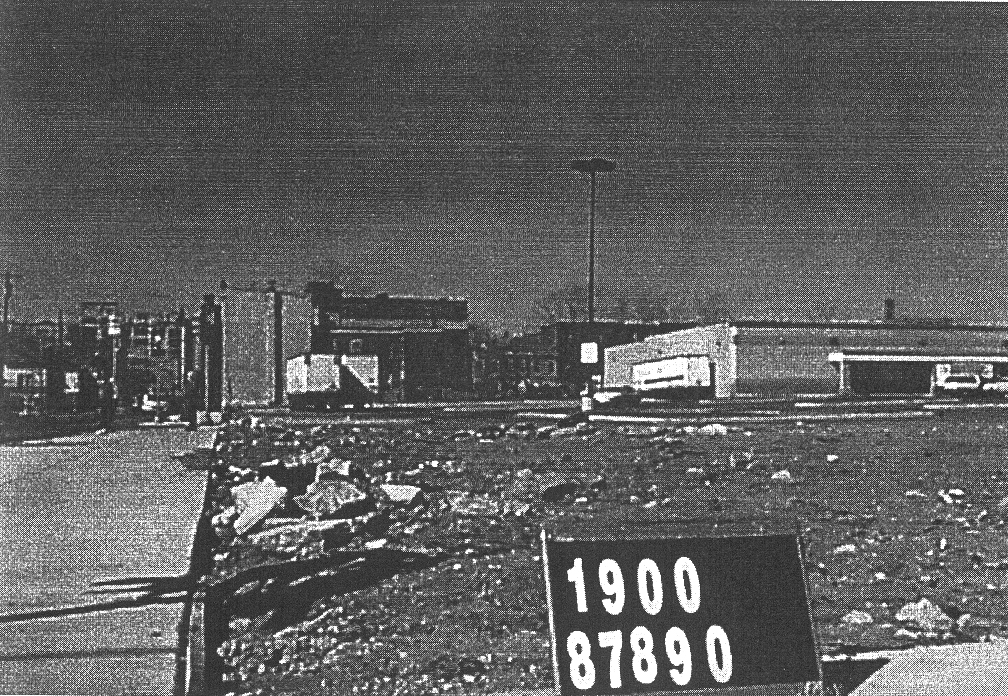

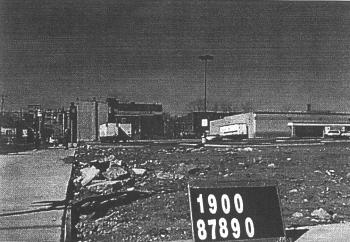

APM would eventually lure a grocery store and credit union to this bulldozed lot on Germantown Avenue.

As businesses and residents moved out, the bulldozers moved in. Beginning in the 1950s and continuing for decades, a series of federal and city urban renewal programs funded widespread demolitions across distressed sections of Philadelphia. Those sometimes-indiscriminate razings reached a peak in the APM neighborhood.

In other parts of Philadelphia, like the Yorktown development to Temple’s south, the teardowns were followed up by big publicly-funded projects. But not in the APM area.

“The problem with urban renewal was that everything was taken down but in a lot of cases there was no money for planning or to put things back,” said Rose Gray.

Indeed, one planning commission document from the 1970s suggested self-sufficiency gardening might be the most practical use for the neighborhood’s vacant lots.

APM’s emergence

Around the same time, a former city Licenses and Inspections worker named Jesus Sierra and a handful of other Puerto Rican activists founded APM. As its headquarters, he picked a small storefront on Germantown Avenue.

At the time, the area’s Puerto Rican population was still growing.

“It was a destination for the second wave of Puerto Rican migration,” said Counwilwoman Maria D. Quiñones-Sanchez, who represents a portion of the APM neighborhood.

The attraction, in part, was the neighborhood’s large supply of scattered site public housing. In the 1970s, most of Philadelphia’s public housing units were located in foreboding towers, which the migrants shunned.

“Puerto Ricans wouldn’t live in the towers. They went to Eastern North Philadelphia because that’s where the scattered site rentals were available,” the councilwoman said.

Manuel Pomales waters the garden in front of his house near Norris street in the APM neighborhood.

Sanchez, who lived in the neighborhood for a time as a child, recalled a few gathering spots and community touchstones, like the Teatro Puerto Rico, which showed Spanish-language films.

But even then the neighborhood was distressed, Sanchez said. Residents with even modest means, including her family, tended to move out as quickly as they could to rent or buy in more stable Latino neighborhoods.

“It’s a neighborhood without a name, and maybe that’s because it was a transitional place for a lot of people,” Sanchez said.

Most of those who stayed behind were impoverished and in need of social services, making the neighborhood a sensible headquarters for APM, which was formed in 1970.

The organization’s earliest days now seem to be obscured a bit by legend. The founders are reputed to have been a tight-nit band of Vietnam veterans. Sierra, who left APM in 2004 and died in 2006, was said to have belonged to one special-forces outfit or another before he worked for the city.

What is beyond dispute is that the organization, which opened with a $30,000 annual budget, quickly grew into one of the largest providers of social services to Philadelphia’s Latino population, offering mental health programs, childcare, drug and alcohol treatment, basic medical services and housing counseling, among other services.

Today, APM’s social programs are available to low-income residents across the city, not just in Eastern North Philadelphia. And the organization has explicitly broadened its mission to serve non-Latinos in addition to its core clientele of Puerto Ricans.

Between its social service program, its community development corporation and its property management wing, the organization operates on a $25 million annual budget with 140 full-time employees.

Michelle Laguna (center) prepares to leave her home located near 6th and Norris streets while taking her kids for a walk.

APM’s heart, though, is still Eastern North Philadelphia, in those blocks past Temple University where the organization began. Its development work, so far, has been strictly limited to that area.

Ruiz said APM got into the development game because it felt it had to.

After helping homeless Philadelphians get back on their feet, APM counselors too often found there was no decent housing available for their clients.

“We were providing housing counseling, but many times we did not have good housing options to send folks too,” said Ruiz.

She recalled long ago visiting a woman in a 3d floor apartment who had covered her busted-out windows with wood planks. It was a cold day, and Ruiz asked her how she kept warm.

“I wear a lot of blankets,” the woman told her.

“That’s why we are trying to rebuild. All of our work is about trying to help the neighborhood become self-sufficient,” Ruiz said. “You can’t engineer a community, but you can give it what it needs to have a chance.”

Coming tomorrow: The vexing issue of vacant land, and the city’s plans for it

Contact the reporter at pkerkstra@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.