Philadelphia among trend leaders in city planning, public health partnership

In Philadelphia and a growing number of other cities across the nation, city planners and public health workers are working together to combat chronic illnesses such as diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure.

The link is especially strong here, where a new position – healthy communities coordinator – has been created to link the two key city departments. Clint Randall, who holds the job funded through a two-year grant from the Centers for Disease Control, has had to hit the ground running.

Philadelphia is in the final stages of rewriting its zoning code and completing its first comprehensive plan in 50 years. “My first major objective is to develop ways public health concerns and policies can be built into these documents,” said Randall, who has a supervisor in both the planning and health departments.

That means focusing on aspects of public health that changes in the built environment can influence. Randall has assessed the current situation and helped planning and zoning policy makers set future goals around access to healthy food, open space and public transportation and the walk-ability and bike-ability of neighborhoods. Much of this early work will be presented to the Philadelphia City Planning Commission in a report that summarizes the health-related goals and recommendations contained within the new comprehensive plan and zoning code. Randall’s presentation will follow the release of the city-wide comprehensive plan, Philadelphia2035, which is scheduled to happen at the Feb. 16 commission meeting.

Recent research Randall gathered shows how much work needs to be done:

From the Public Health Management Corporation, he learned that Philadelphia County has the highest prevalence of adult obesity (35.1%), diabetes (11.9%), and hypertension (33.4%), and the second highest prevalence of heart disease (4.5%) among the counties containing the 10 largest cities in the country. In 2008, nearly two-thirds of adults and half of the children here were overweight or obese.

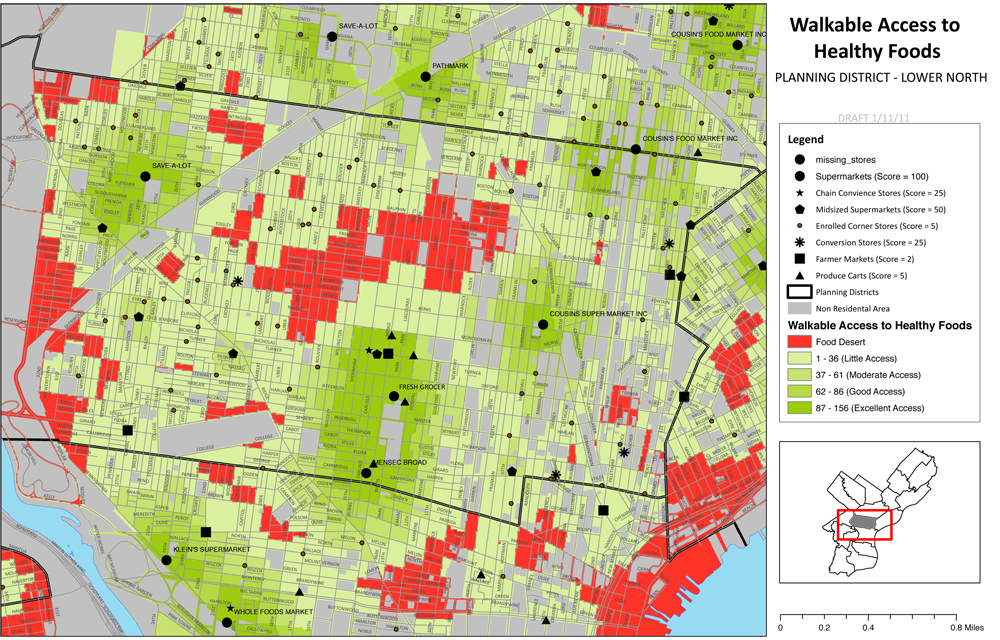

The Food Trust discovered that “residents in low-income Philadelphia neighborhoods are half as likely to have access to quality grocery stores as residents of high-income neighborhoods,” the report states, and while progress has been made through PA Fresh Food Financing Initiative, many areas of the city remain under served, except by corner convenience stores. In 2009, the journal Pediatrics did a special report on corner stores, and revealed that “Philadelphia school children buy, on average, 360 nutrient-poor calories from corner stores for the cost of little more than $1 per visit,” Randall writes.

The obesity problem is both a food and an activity issue.

“A lot of people like to say that physical activity has been designed out of most people’s lives” Randall said. The oldest parts of the city are walk-able, but in the 1950s, and after, suburbanization didn’t just strike suburbia, he said.

Dr. Giridhar Mallya, the director of policy and planning in Philadelphia’s public health department, said awareness campaigns that encourage people to get active and eat right are important, but design that fosters activity and health is crucial, too. “If we can allow them to be active during their normal, daily routines, we will get a big bang for our buck,” he said.

After the city-wide plan is presented to the planning commissioners on Feb. 17, work will begin on 18 district plans – more detailed work for clusters of neighborhoods with similar characteristics that will set specific development goals based on those neighborhoods’ needs. Randall is developing a set of database-driven tools that will be used to set baselines on public health indicators including the distance people who live in an area have to travel to buy fresh food, the accessibility of public transportation, and the amount of bike and walking trails and green space. Goals for improvement – or maintenance where things look good already – will be set. Then the tools will be used to measure progress in years to come.

These tools are collectively called PHILATool. That stands for the Planning & Health Indicator List & Assessment Tool.

Food access in Lower North Philadelphia

Randall is also training many people in both the planning and public health departments on how to use these tools, said Community Planning Division Director Richard Redding, Randall’s planning department boss.

What pleases Randall is that he and the others who are trained in using the tools will be able to help community leaders use them to learn more about – and fight the problems in – their own neighborhoods. And PHILATool is just the beginning.

During the district planning process, planners will be seeking on-the-ground information from neighborhood residents. Randall has developed walk-ability and bike-ability survey tools through which citizens can help gather even more detailed information about the places they live.

Just as important as the new tools and training is the up-tick in communication that has resulted from Randall’s cross-department work, Redding said. Discussion between the two departments used to be mostly concentrated during annual capital budget discussions, he said, but “the addition of Clint has opened a whole new level of dialogue.”

A little planning history

This is not the first time people interested in improving the urban environment and the public health have worked together to fight disease.

At the turn of the last century, “The planning profession largely grew out of response to contagious diseases,” Randall said.

University of Pennsylvania professor Eugenie L. Birch, the chair of urban research and education and a planning history expert, said that both the city planning and public health professions were in their infancy then, and there was not as much delineation between the duties of the two groups.

“Cities at the turn of the century grew very quickly, particularly in northern and middle-western industrial cities,” Birch said. “There were no regulations or ordinances on how you could build neighborhoods and housing, and speculators built as fast as they could to accommodate throngs of people. If you were living in a tenement in a city like New York or Philadelphia, you had no air and no light. There were no windows. The toilet was in your back yard and there was no drainage. These were huge concerns.”

People who were interested in civic improvement – early planners and early public health workers – noticed the relationship between infectious disease and poor housing, Birch said, and they worked together to pass laws and create infrastructure that would control the problem.

The separation between the nascent planners and public health workers started to happen around 1920, as the professions began to further specialize into distinct areas of expertise Birch said. “City planning became more dominated by architects, engineers, lawyers, real estate developers and so forth,” she said. They began to focus on zoning and budget reform, she said. Social workers and health professionals concentrated more on public health concerns, she said. Both groups worked on important issues, Birch said, but they mostly worked separately.

Coming back together

At first, the renewed connection was academic. “In the last 10 years, there has been a lot of research coming out of both the planning and public health fields about the connections between public health and built environment – physical activity, access to food, climate change and some of the implications for public health related to that,” said Kimberley Hodgson, manager of the American Planning Association’s Planning and Community Health Research Center – a unit formed about two-and-half years ago with the goal of helping to better integrate public health and planning.

At first, the research focused mainly on weight and access to public transportation, Hodgson said. Basically, people who live in areas well served by public transportation tend to weigh less, because they walk to the boarding point. In the past four years, the built environment/public health research has expanded to issues around food access, climate change, and other issues, Hodgson said.

It’s not just academic research that has shown health departments and planning departments that they need to work more closely together, Hodgson said. Pressure is coming from the public.

“In Baltimore, food access disparities were realized mainly because of community meetings,” she said. When updating their comprehensive plan in 2006, planners in that city went into neighborhoods to ask residents what issues they faced. “They found out there were a lot of issues related to inadequate food access, but they didn’t know what exactly to do. So they partnered with public health,” she said.

When King County, Washington – read Seattle – was redoing its comprehensive plan in 2008, planners asked the public health department to work on it with them, from the earliest stages, Hodgson said. Their plan is one of the few in the nation that thoroughly addresses food access issues, Hodgson found in her research. It equates access to quality food to access to clean air and water.

In Hennepin County, Minnesota – where Minneapolis is located – a planner with a dual masters degree in planning and public health works full time for the county health department, she said. “It’s an evolving trend, but it’s not a very common trend right now,” Hodgson said. “I wouldn’t say this is quite mainstream yet.”

Hodgson does not know of another city where a planner has one foot in the health department and one foot in planning, she said. “That is really exciting and great to hear,” she said when told about Randall’s position.

Randall spent the first months in his job researching what was happening elsewhere, and while he didn’t find any direct role models, he has found that other places are doing good work in this area. New York City, for example, has a whole book of active design guidelines to help make areas as walk-able as possible.

Increasing mixed use development – the type that’s often praised for its urbanity – would do a lot to help get people moving more, Birch said, but it won’t be easy retrofitting changes into built-up environments.

The suburbs and suburb-like portions of cities are tightly structured around the automobile, she said. But even people living in walk-able portions of the city may find they have to drive to take care of their daily needs. “The economics of the corner store are no longer viable. Now people get in their cars and drive to a big box or a supermarket,” she said. And even people who live in the city may drive to the suburbs for work.

The health and planning reunion, Philly style

Randall’s salary is paid for by the public health department, with a portion of a $25 million, two-year Centers for Disease Control grant.

With the zoning and planning overhaul underway, a city planner is a wise use of health department resources, said Mallya, the public health department’s director of policy and planning.

“Where people live has a profound impact on their health, both short and long term,” Mallya said. “You can look at something even as definitive as someone’s life expectancy and see how that differs from city to city, even from neighborhood to neighborhood,” he said.

The good news, from his standpoint: “The built environment is not only a predictor of people’s health, but something you can change through policy, laws and programs.”

Having a health planner in the planning commission means health issues are considered while planning is done, Mallya said. “We can be creative and really think about how we can align planning and zoning decisions to promote walk-able and bike-able neighborhoods, promote transit-oriented development, and linking people and their neighborhoods to sources of healthy and affordable foods,” he said.

Randall talks about his job at an aging symposium.

Forty-three other communities won similar CDC grants, Mallya said, but Philadelphia is the only one he knows of that has used the money to pay a city planner’s salary.

More about the tools

Each of the assessment tools Randall has or will create is intrinsically tied to a goal within the comprehensive plan and, subsequently, the district plans.

For example, one goal is to strengthen neighborhood centers – concentrating civic and recreation spaces and other public amenities in one area and fostering a business district. Data collected from the Planning Commission, Parks and Recreation and the school district will show the proportion of households within half-a-mile of a public amenity or cluster of amenities. Commerce Department statistics will show how many retail establishments are created in each community center. Planning Commission data will compare the total number of parcels zoned commercial to the number that are vacant.

Beneath these tools that will allow planners, and eventually the public, to gauge the health of their neighborhoods is a whole lot of data that Randall has been gathering from city departments and agencies and other organizations.

Mapping software can pinpoint the locations of places where fresh fruits and vegetables can be purchased, and then used to determine the proportion of a district’s population that lives within walking distance of one, Randall said. Similar software can determine the distance people must travel to get to a park.

A blend of maps and statistics can also indicate places where more crosswalks are needed because there have been a disproportionate amount of vehicle/pedestrian accidents, or where traffic congestion may be leading to higher incidents of respiratory ailments.

The tool will help planners determine if neighborhood walk-ability is being eroded by a large number of variances allowing curb cuts. It will show how many miles of multi-purpose trail have been created or are in the pipeline. It will show where planning-related grant money is going.

Layering multiple maps will provide even more valuable information, Randall said. For example, a host of factors may contribute to food access decision. Planners may consider obesity rates, car ownership rates, walk-ability and healthy food access, for example, when deciding whether to change zoning to allow for produce markets or farm markets.

Even more detailed analysis may be needed when planners are putting together the district-level plans, and laying the new zoning classifications onto city maps, Randall said. For example, obesity rates may be higher than expected in a neighborhood that has a grocery store nearby. But when planners meet with people who live there, they may discover that getting to that store requires crossing a dangerous intersection.

In that example, doing a health impact assessment report on that smaller area with additional data gathered from the community through a walk-ability assessment, could help planners see that a planning approach is needed – a new crosswalk.

Organizations will also be encouraged to use the walk-ability survey and a similar bike-abililty survey for their own purposes. For example, Randall said, a walk-ability or bike-ability survey study may help bolster the need for grant money to build more trails.

What’s next?

On March 1, the Planning Commission will launch a website for the comprehensive plan, Philadelphia2035. Maps and other community health information that is generated will be posted.

While there isn’t funding to do this now, Randall hopes to eventually create user-friendly software that will allow the public to easily interact with the data and maps, and layer them one upon the other to get a complete picture of their neighborhood.

In the meantime, planners will frequently post both city-wide and neighborhood-level maps that they produce during their analysis.

Randall said it is crucial that neighborhood residents examine these maps. This is how planners will know when their data isn’t telling the complete story, he said.

A public meeting on the comprehensive plan will be held in March, with district-level public meetings to follow in April.

Reach the reporter at kgates@planphilly.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.