Is Philadelphia suffering from mural fatigue?

During the past few weekends, a dozen or so budding artists have taken glue in hand to painstakingly apply bits of shattered mirrors and smashed plates to the side wall of a large building.

They’ve signed up for a course in mosaic-making under the tutelage of celebrated artist Isaiah Zagar — but not everyone is happy about their presence. That’s because the quaint street that will bear the results of their work is Bradford Alley.

It’s a small street inhabited by residents who, as previously reported in PlanPhilly (http://planphilly.com/one-little-street-some-big-questions:), can be fiercely protective.

“I’m very unhappy about the mural,” says Gerrie Schmidt, who contacted PlanPhilly — and several neighborhood associations and city representatives — once the project got underway. “I can’t stand it,” she added. “It’s trashy-looking, and it brings South Street right into Bradford Alley.”

Despite Schmidt’s strong words, she insists that her beef is not with Zagar, but with the owner of the wall.

“She never gave us any notice that this was under consideration or was going to happen,” Schmidt says. “Shouldn’t people who reside nearby have input to what’s going on? It seems like something that people who are interested in quality of life issues in Philadelphia should think about.”

Her question brings to mind a similar one that was recently raised by an ongoing Mural Arts Program installation at Bodine High School.

In that instance, it wasn’t a handful of neighbors that were displeased, but the Philadelphia Art Commission when some members wondered whether a mural should have been allowed to sprawl over the intact school building.

Does the city have mural fatigue at this point?

Are these well-intentioned arts organizations running rampant — and have they run their course?

Gary Steuer, the city’s chief cultural officer has given the matter some thought. “My sense is that the city isn’t overly-muraled — in fact, in many areas, there’s still a huge demand for Mural Arts projects,” he says.

Then he continues: “but we should be looking for quality over quantity at this point.”

Both Zagar and Mural Arts stem from the wish of their founders to uplift struggling neighborhoods by making art a community effort, observes Ellen Owens, executive director of Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens, Zagar’s nonprofit arm.

“That said, location still matters,” she says. “If Isaiah wants to do a wall in a dark alley, everyone loves the idea. If it’s close to private homes, it doesn’t necessarily get the same reaction.”

In cases such as Bradford Alley, where the property under question is privately-owned, it’s usually left to the owner to deal with neighbors.

“Of course, it’s always nice to involve the community,” Owens says. “And usually when people are consulted from the beginning, things can work out.”

Private party, yes but in the public realm.

Schmidt, the Alley resident, says she contacted Mural Arts to get a sense of their “best practices” when it comes to community involvement.

The organization, which traces its history back to 1984, goes out of its way to win community buy-in. And, indeed, according to executive director and founder Jane Golden, Mural Arts has “always valued an intensive process where we build a connection between the artist and the community.”

So, what happened with Bodine? Golden says she was “really surprised to hear that response from the Commission — but it’s a point well-taken because we try not to do our work in a silo.”

Although the program has appeared before the Commission for other recent projects, such as one at Philadelphia International Airport, Golden says it has never done so for school building work. “We go before the School Reform Commission,” she says. Still, with 3,000 murals under its rapidly-expanding belt, the program is ready for a change, a tightening of focus, Golden admits.

“We thought that to be good public servants, we needed to keep up with demand and do a lot of work,” she says “We’re not interested in creating another 3,000 murals. We need to think about preserving what we’ve created, and to think more carefully about the communities and places where we work, and the artists who we work with.”

Golden has cited a recent Center City mural, created with the well-known street artist Kenny Scharf. as one example.

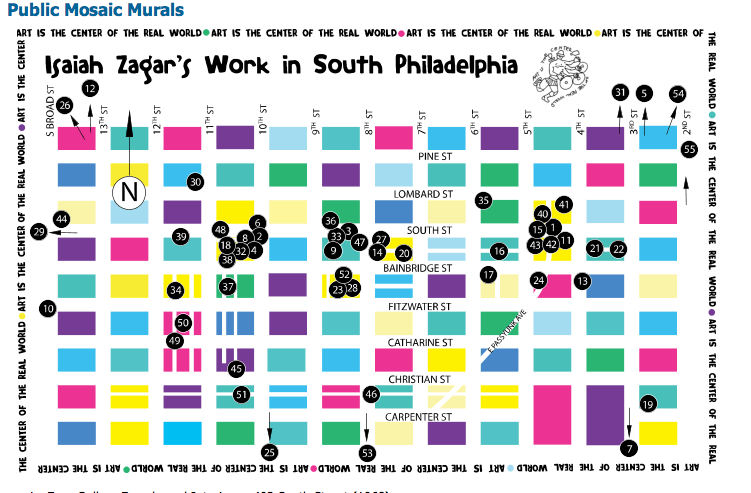

And, an argument might be made that Zagar himself fits the bill. Although some may roll their eyes at another garish mosaic, the artist is much more than an eccentric whose work should be relegated to the side streets around South Street. In fact, more than 100 walls in the city are imprinted with his quirky assemblages — including, notably, those at Old City’s Clay Studio and Painted Bride — and his work is included in the permanent collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, and D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum.

“This is a world-renowned artist, and he came to us and asked if he could use our wall,” says Deen Kogan, who more than 50 years ago started Society Hill Playhouse.”The side of the building already has a mural from the ’70s and needed substantial re-doing. Frankly, it never occurred to me that anyone would object.”

And not everyone does. “I love it,” says Stan Shmia, as he turned onto Bradford Alley, where he lives. “It says we’ve arrived — we’ve been Zagared.”

Shmia, who says he also welcomed an out-of-scale house down the block that others fought, adds: “Philadelphia is all about the mish-mash. It’s part of what it is to live here.”

Contact the reporter at jgreco@planphilly.com and follow her on Twitter @joanngreco

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.