John Gallery looks back on a decade of historic preservation

John Andrew Gallery, the executive director and soft-spoken lion of the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, will leave the position at the end of 2012.

The organization announced it would conduct a national search to fill the job upon Gallery’s retirement, though it may be more accurate to say the 72-year-old isn’t so much retiring as moving on to his next occupation.

A Boston native and graduate of Harvard College and Harvard University Graduate School of Design, with a master’s of architecture, Gallery worked with Edmund Bacon at the Philadelphia City Planning Commission in the 1960s. He was associate and acting dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Texas and chair of its Department of Community and Regional Planning in the early 1970s.

In 1976, Gallery created Philadelphia’s Office of Housing and Community Development and served as director through 1980. He then co-founded Urban Partners, a private consulting firm focused on planning and implementation of socially oriented real estate development, with an emphasis on historic preservation.

He is the author of “Philadelphia Architecture: A Guide to the City,” in addition to several other books and numerous articles and papers.

In 2002, he became director of the Preservation Alliance.

Gallery sat down with PlanPhilly last week to talk about a decade of historic preservation work in Philadelphia, the achievements of the organization, and the challenges ahead for his successor.

What path led you to the position of executive director of the Preservation Alliance?

Gallery: For many years I was involved with a consulting firm called Urban Partners, which I founded along with two other people. It still exists and legally I’m still a minority partner. The idea of Urban Partners was to focus on what we refer to as socially motivated real estate development – low income housing, neighborhood development, community development projects. So a lot of our work was with nonprofit organizations. Over the years, one of the things I had gotten very interested in was working with nonprofits and developing a strategic plan for their organization.

I’d also done a fair amount of work on historic preservation. I was a consultant to various developers for the Lit Brothers Building. I also worked on a study of the historic houses in Fairmount Park, which was the genesis for setting up the Fairmount Park Historic Trust. So we had done a fair amount of historic work, plus we had this interest in strategic planning.

In 2001, a couple of people on the board of the Preservation Alliance asked me to do a strategic plan. This was a period when they had let a lot of staff go, funding was difficult, and they didn’t know what was going to happen. It was around the same time that the Foundation for Architecture ran into financial problems and went out of business.

My interest was two-fold: I had always enjoyed working with nonprofit organizations on strategic issues. But I also felt that we could not have the Foundation for Architecture and the Preservation Alliance both collapse. In many ways I felt the Preservation Alliance was an important organization for the city. And a lot had been done to merge the Preservation Coalition and the Philadelphia Historic Preservation Corporation [in 1996] to create this organization. At one point I had been president of the board of the PHPC, before the merger.

So that’s how I got involved. I got invited to serve as a consultant to work on a strategic plan, and I did that. And there was a core leadership of the board of the Alliance that was getting the organization on the right path. At the end of it, we looked at it and said, OK, it’s an interesting plan, but we don’t really have an executive director. We don’t have the money to hire an executive director. No one in a good job is going to leave his job given the task, “Here’s your job, now go raise a salary.”

I suggested to the Alliance, “I’m a consultant, so why don’t you buy 50 percent of my time, and for a couple of years I’ll start implementing this strategic plan, and raising money? Then we’ll have created enough stability and confidence that you can go and hire a real executive director.”

I started as a consultant, but increasingly I become so identified with what I was doing at the Alliance that it was very hard for me to continue serving as a consultant at Urban Partners. … At some point I just said to my partners, I’m taking a leave of absence. Eventually, I switched from being an Alliance consultant to being an employee.

Why did you choose to leave this year?

Gallery: It was a combination of things. It’s a demanding job, and I make it a more demanding job. I tend to throw myself fully into whatever I’m doing. But I don’t have quite the same amount of energy I had 10 years ago.

Also, I’m not a person who’s ever held a single job for 25 years. All of my jobs have had some relationship to planning, architecture, and community development. But I found it to be stimulating to my own growth to try and do certain different things.

I also think that sometimes it’s healthy for an organization to change. I think that in many ways, and I don’t say this egotistically, there’s a high degree of identification between me and the organization. I think that’s good, but it’s also a weakness. That is, the organization needs to be able to stand on its own.

About two years ago I said to the board, you need to start thinking about a plan for succession. Last year we were doing the strategic plan, I was still saying you need to start thinking about my leaving, but I was still not saying exactly when I was leaving. It just became apparent that they couldn’t really start to plan for me to leave unless I said when my time to leave was. So last year I said let’s assume the end of 2012, which I felt would give everyone sufficient time to work things out.

So it’s a combination of a change for me in terms of what are the other opportunities for me in my declining years. It’s a new challenge for me, and I think it’s a healthy thing for the organization.

What are some of the most important accomplishments of the Alliance over the past 10 years?

Gallery: I haven’t thought a lot about this. But when I do think about it, it isn’t specific properties that I think about as being the most important things.

The more important thing that I’ve tried to do over the last 10 years is to broaden the concept of what historic preservation is. I’m not saying people in Philadelphia before hadn’t had a broader view, but there’s a tendency to think of historic preservation in relation to Philadelphia’s Colonial history, Center City, the more affluent neighborhoods, which were the first historic districts. I think the core of many of the things that we’ve tried to do is to broaden the meaning of preservation, and in doing that, to broaden the participation in preservation to people who have not felt connected to it before.

There are lots of ways we’ve done that. Neighborhood programs, obviously. Getting out into neighborhoods that previously wouldn’t have thought of themselves as historic. Engaging with people in those neighborhoods, and getting them to think about things in their neighborhood that they’d really miss if they were gone.

We’ve also tried to get people to think more about mid-20th century architecture as being part of the spectrum for historic preservation, and trying to translate that into action. So we’ve nominated to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places important 20th century buildings, such as Louis Kahn’s Richards Medical Center.

And we’ve supported historic districts, including the Parkside district, the first African-American neighborhood to be nominated as a district since Diamond Street was done in 1986.

We’ve certainly been trying to raise those issues up to broader public awareness.

To me, that’s the more important thing – making preservation more broadly relevant to the type of population that exists in Philadelphia and, hopefully, thereby making it a high priority for public policy and city government as well.

I think we’ve been successful in that. I think we have reached out to neighborhoods. I think we have gotten people to think differently. I think we have much more diverse representation from different parts of the city at many of our activities.

We just started a program for what I call the “emerging leaders in preservation” who wanted to take a more active role in either their own community or getting on the boards of preservation organizations. It’s a small group, because we want it to be a hands-on kind of thing. It is 50 percent men, 50 percent women, 50 percent white, 50 percent black, some people in their 20s and 30s. And all of those people applied; we didn’t go pick them. That’s a good indication to me that what we were doing was reaching that type of diversity, which I think is important to give strength to preservation in this city.

Have you seen a change in city policies over the past 10 years because of the advocacy of the Preservation Alliance?

Gallery: I think you have to make a distinction between the city – referring to the political administration – and the staff of the Philadelphia Historical Commission.

I don’t think I’m seeing much change in the city policies. I think it’s still very difficult to get preservation perceived as a high priority with all of the competing priorities, particularly in the recent economic situation.

I think that the current staff of the Historical Commission – and I don’t mean to criticize the past staff – but I think they share the same understanding of preservation being a broad thing. An example would be when we did the nomination of the Kahn building at Penn, the Historical Commission staff did a nomination for Robert Venturi’s Guild House. They are the two icons of that era. That reflected the Commission’s understanding that the mid-20th century has become important.

What were the most important buildings that were lost over the past decade?

Gallery: If you think about this period, the feeling I have is not so much a sense of loss, but a sense of gain. Ten years ago, what were the big preservation projects? The Victory Building was Number One on everyone’s list. Here’s this vacant, beautiful building, what’s going to happen with it? The Naval Home was vacant for 25 years. What was going to happen with it? Those have all been saved. More things have been saved than have been lost.

The Naval Hospital, one of the great Art Deco buildings, was lost. But it’s still my feeling that there hasn’t been anything of truly great importance that has been lost. And the things that were really important during the first half of this decade, when the economy was strong, like the Victory Building, benefited from it.

What do you hope will happen in the next 10 years in historic preservation in Philadelphia?

Gallery: I hope the economy turns around a little bit to the point where it becomes possible for the public sector to put some money and incentives into historic preservation. I think what will be desirable to see happen is for something to kick-start it.

One of the more important things we do at the Alliance is the Historic Property Repair Program. Philadelphia has an incredibly rich heritage of residential architecture. Not just Society Hill or Chestnut Hill, but houses in West Philadelphia and North Philadelphia. The architectural heritage of those neighborhoods is amazing. One of the biggest problems in those places is not the problem the community development organizations focus so much on, which is vacant houses and vacant land. The problem is the occupied houses that need serious repair.

When we first started the program, we received 400 applicants, and we never advertised again. To me, that’s really the big preservation issue. You hear about the Divine Lorraine, the big landmark buildings that get a lot of attention. But it is the quality of neighborhood life that defines Philadelphia. You go into some of these areas and go, “Wow, this is amazing.” And yet, they all need investment.

What we found in the program is that people love their houses. They simply didn’t have the resources; they had some resources, but not enough. The focus on preserving the existing occupied housing to me is much more important than the focus we’ve traditionally had on all these vacant houses. I’m not saying that’s not important, but keeping the things that people are already living in and upgrading them, from a preservation point of view, I think should be a top priority.

That’s something I would like to see happen. I’d like to see less of the city’s block grant money and things like that going into new construction on vacant lots and more of it going into supporting the existing fabric of occupied housing. I think in the long run, that’s what is key to preserving the strength of Philadelphia neighborhoods.

What challenges will your successor face?

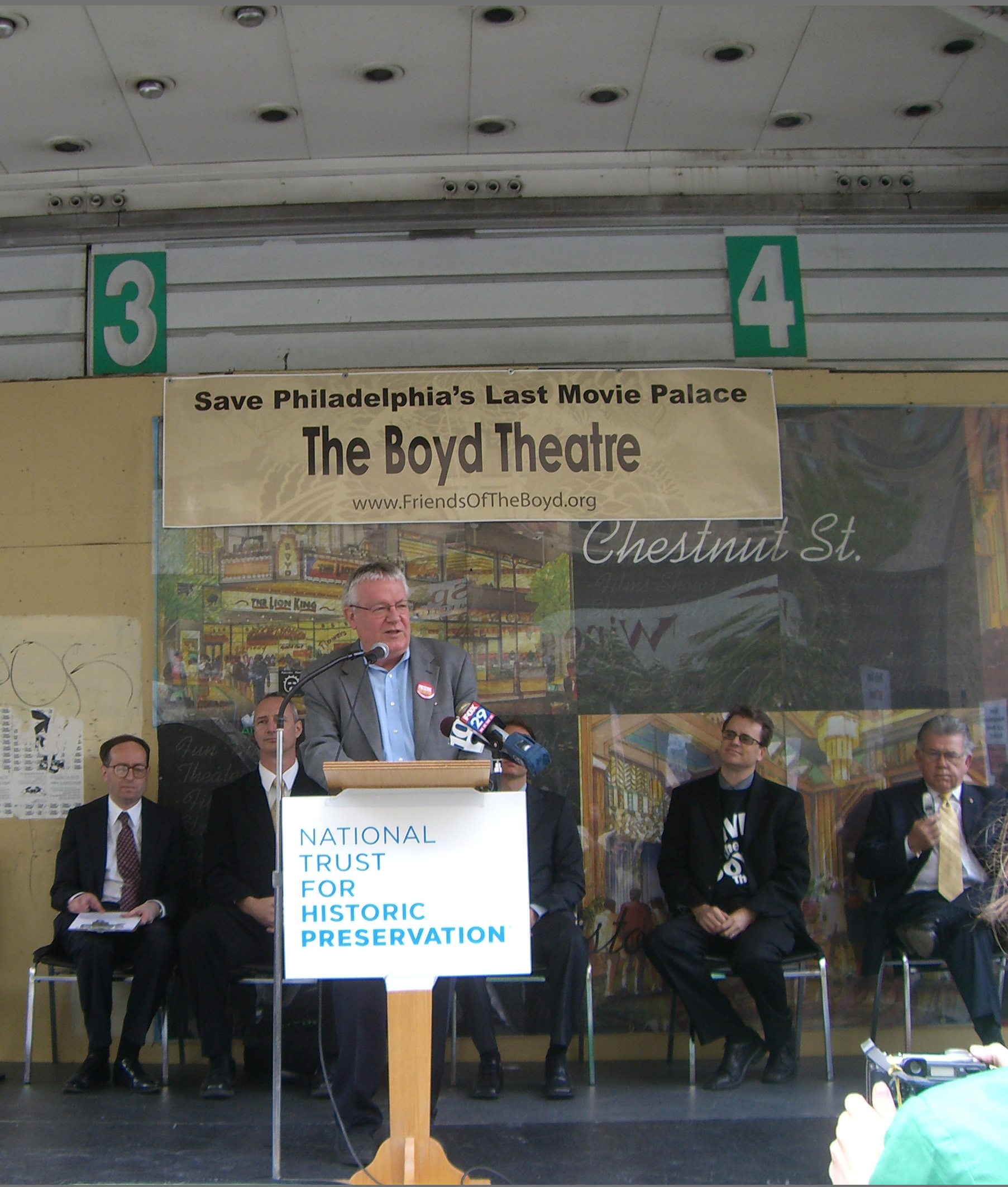

Gallery: I think that my successor is going to inherit a number of important things that haven’t been resolved. A classic example of that is the Boyd Theatre. We’ve spent 10 years trying to figure out how to do something with that and haven’t been successful.

There are a handful of things that are old things, but are still worthy things.

I think the big problem for whomever takes over is trying to figure out a way to mobilize public support for preservation. Not just for people showing up when there’s a problem, but viewing it as a high priority that people will make a long-term commitment to.

For me, one of the things I find disappointing, and surprising, is that the Alliance has a very small membership. I talked to my friend in Los Angeles, and their membership is 10 times the size of ours. We have about 700 members in Philadelphia.

Like many other organizations in recent years, people have not been able to renew their memberships. But in a city like this, with the heritage that Philadelphia has, one would think there would be more people who belive that having an organization like the Preservation Alliance around would be worth 50 bucks a year.

It’s not just the money; it’s also the indication of the value the general public places on preserving things.That’s the challenge for whoever comes into this job: how do you mobilize the public? How do you get younger people to feel that preserving the historic physical character of the city is a priority? I think that’s still the biggest challenge – mobilizing public interest.

What are you going to do next?

Gallery: I really have no answer to that. I have no idea. It’s not something where I said, “Now I want to do this.” Several times in my life I’ve said, “Now I’m going to stop and open up the possibility of something new to happen.”

The only thing I have in my mind at the moment is, for quite a few years I’ve been working on a book about William Penn’s original plan for Philadelphia. My one goal is to gather all of my miscellaneous notes and drafts.

For me, it’s really what kind of opportunity is going to come around that I will make myself available for by leaving here? That’s what I’ve done several other times in my career. I’ve found myself doing things I wouldn’t normally have planned to do, but have turned out to be really worthwhile experiences.

You asked in the beginning about what important projects were saved. There are two that stand out in my mind.

The first is the Nugent Home for Baptists in Germantown. It is one of those examples of surprises: why wasn’t that building ever put on the Philadelphia Register? Lots of people admired it.

The thing about the Nugent was, people in the neighborhood contacted us. It had been for sale for a long time, and there was an organization that was getting ready to buy it and wanted to demolish it, along with the building next door, the Presser Home for Retired Music Teachers. The people in the neighborhood said, “We have someone who has been trying to do a nomination for the Presser, but no one is doing anything for the Nugent. Will you do it?”

We wrote a nomination, and the Historical Commission staff was very cooperative. They looked at it very quickly, determined it was complete, and set a hearing. That prevented the demolition of the building. The commission held a special meeting solely on that because there were so many people interested; it was in the City Caucus Chamber and it was filled to capacity; there must have been 200 people. And it took two hours. It was the most dramatic meeting that I’ve ever been to at the Commission. And they approved it. To me it was like that old phrase, snatching something from the jaws of death. That building was so close to being lost. It was a matter of really engaged people in the community who wanted to save it.

The best part of the story is that the Presser Building is now totally rehabbed and occupied as age-restricted housing development. And the Nugent project is completely financed and rehab construction will probably begin in the spring.

The other example is a very personal one. It was the N.W. Ayer Building on Washington Square. It was a former advertising company that had its offices in one of the nicest and most important Art Deco buildings in the city. The developer who owned it, like many developers years ago when the condo market was still hot, wanted to put an addition on the roof of the building. He hired an architect to design an addition that was a very contemporary glass and steel, sitting on top of this Art Deco building.

I found the idea of putting on the addition as being a mistake to begin with. Also, the design of it – I’m much more sympathetic to the idea of creating additions that are compatible to historic buildings rather than dramatically different. The architect thought of it as a searchlight on top of the building. I thought of it as a spaceship from Mars that had landed on top.

It went to the Architectural Committee of the Commission and they approved it. It was mind-boggling to me. The developer went to the commission, and I decided I was going to make the strongest case I could against it.

I had taken a lot of pictures and I had strips of paper that simulated what this thing would look like on the top of the building. I put up my photographs, and each time I explained one, I would rip off this little piece of paper showing what the building really looked like with this thing and without this thing. And when I finished, the person who had made the motion to approve the project said, “I withdraw my motion.” And they turned it down.

It was the same sort of feeling. At the last moment, you felt like you were able to do something.

Contact the writer at ajaffe@planphilly.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.