What it would take to build an earthen berm for flood control on a section of Cobbs Creek in Eastwick

The actual construction of an earthen berm to control flooding along Cobbs Creek in Eastwick would likely take only a couple of months.

But it will take significantly longer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Philadelphia Water Department to reach agreements on funding and maintenance, determine whether a berm is the right solution, design the right structure if there is one, and potentially acquire land, said Erik Rourke, strategic planner for the Army Corps of Engineers Philadelphia District.

The Eastwick flooding issue came to the fore last June, when developer Korman Residential sought a zoning variance to build a large apartment complex on redevelopment authority land the company has held development rights on for decades. It can build single family homes by right, but the option is set to expire in coming years.

Korman also holds development rights on another 93 acres adjacent to the site of the proposed apartments, but it would turn those back to the city under part of a proposed legal settlement – a dispute over how much the city paid Korman for another, unrelated parcel. The city’s intent is to allow that land to be used for future airport expansion.

Earlier this week, Philadelphia Water Department Commissioner Howard Neukrug told City Council’s transportation and utilities committee that convincing the Corps to build an earthen berm on Cobbs is an essential part of fixing Eastwick’s flooding problems, which was the subject of the Tuesday hearing.

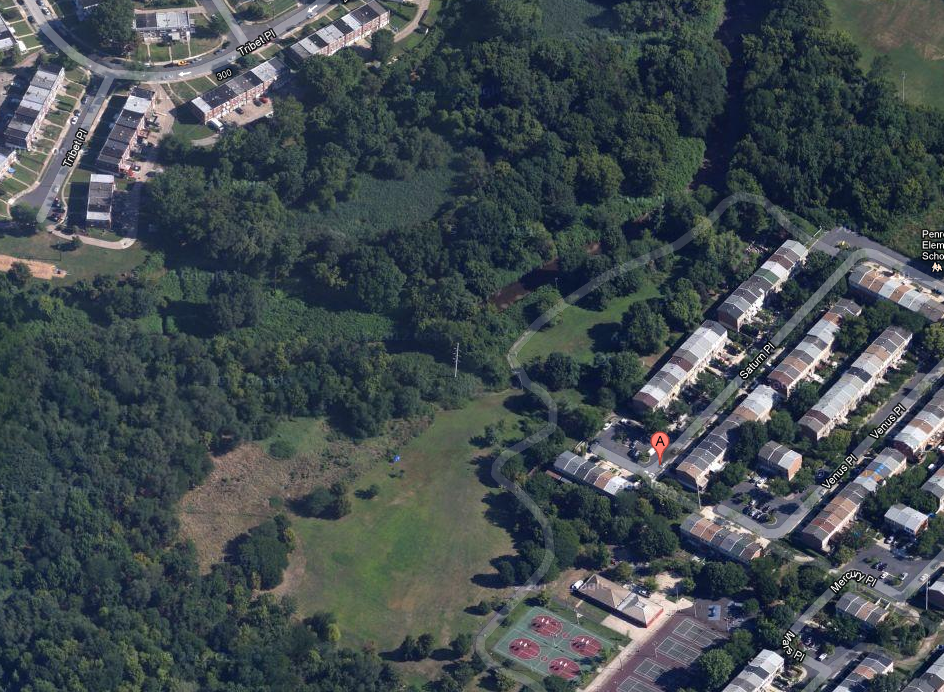

After the hearing, Neukrug explained to PlanPhilly that during significant rain events, Cobbs Creek is overflowing its banks, and a water department analysis, while still ongoing, suggests strongly that is responsible for most of the flooding in nearby sections of the neighborhood.

During Hurricane Floyd, which struck in 1999, the creek overflowed and covered the area with four- to five-feet of water, Neukrug said. “The flow was like the Schuylkill River,” Neukrug said. “I can never build my sewers big enough to handle that.”

Neukrug said the construction of an earthen berm would be relatively simple. The ground already rises in the area, he said. In a follow up email, Chris Crockett, Neukrug’s deputy for planning and environmental services, said the berm would need to be roughly two blocks long, or about 1,100 feet, and likely four- to six-feet high.

But much must happen before there is any construction.

A Partnership Agreement

If a flood control project for Cobbs Creek is in the cards, the Corps and the water department would be partners through the study, design and construction process. They would share funding responsibility. And then when the project is finished, the Corps would turn over operations and maintenance to the city, the Corps’ Rourke said. So the first step is continuing the Corps-PWD discussions to see if an agreement can be reached between the parties, he said. An agreement spells out each party’s responsibilities.

In order for the Corps to take on a project, the project must fall under what is called an authority – basically, an act of Congress that authorizes this type of project, and sets the guidelines for federal funding.

Rourke said current discussions include determining which of several different water resources-related authorities would best apply to this project. Depending which one it is, the cost share could range from a 50-50 split between the federal government and the city and a 75-25 split, with the federal government picking up the greater percentage, Rourke said.

Once the right authority is determined, the Philadelphia District would seek funding authorization from national headquarters.

Neukrug estimated it would cost several million dollars to build the earthen berm in Eastwick. Rourke said that is a good starting point, but it could go higher, depending on existing conditions – including whether any privately owned land would need to be acquired, or right-of-ways obtained. A cost estimate is part of the study and design process, he said.

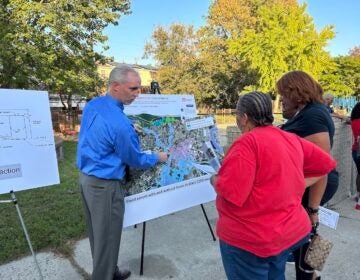

“We need support from the community, from City Council and from our Congressional delegation,” Neukrug said after the hearing earlier this week.

The funding must be in place before the agreement can be signed, Rourke said, but not the entire amount – just the amount that would be spent in the current fiscal year.

Rourke said reaching an agreement generally takes between three- to six-months, but that is in an “unconstrained fiscal environment.” In other words, with budgets being tight, it could take longer.

Once an agreement is reached, the studies would begin.

Crockett and Neukrug stressed that studies would need to be done to determine, among other things, what impact a berm would have on downstream neighbors.

Exactly right, said Rourke. “One of the things the Army Corps of Engineers cannot do, we cannot pass the burden of flooding to somebody else downstream.”

Rourke said studies would not only consider a berm, but other flood control measures and actions, including what will happen if nothing at all is done.

He doesn’t know yet what alternatives will be studied in Eastwick’s case, but options include building a flood wall or other structure rather than an earthen berm, or creating a holding pond that would contain excess water in heavy rain events.

Yet another option: The acquisition of flood-damaged homes. If there are homes that are regularly flooded, “it might make more sense just to buy those homes out,” Rourke said.

Any sort of berm, levee or flood wall means extra water stays in the stream channel rather than spilling beyond the wall, but it has to go somewhere, eventually. The Corps’ hydraulic engineers would study existing conditions and create models of what happens in a flooding event now and what would happen if a berm were built, Rourke said.

A complete environmental impact study would also have to be done, Rourke said. This would determine the impact of a solution on any threatened or endangered species in the area.

There are two Superfund sites in Eastwick. When asked if this could complicate the project, Rourke said the Corps must always look for the presence of any hazardous, toxic and radiological waste on a project site. If any is found on site, “it is the non-federal sponsor’s responsibility to clean it up,” he said. The city is the non-federal sponsor in this potential partnership. “A project could get put on hold until the site is remediated.”

Rourke said the general time frame for the study phase of a project is six months to a year.

Once studies have been done to determine the best approach to a project, and the potential impacts, the project would be designed, Rourke said. Design takes about six months.

Once design is complete, building a project the size of what’s under discussion for Eastwick would take “a couple of months,” Rourke said, but that time frame changes if there is real estate to acquire.

The perspective of Eastwick Friends & Neighbors

“Finding a comprehensive solution to catastrophic flooding in Eastwick is not just a good idea, it’s a necessity,” said Amy Laura Cahn, an attorney from the Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia who is representing the Eastwick Friends & Neighbors Coalition. “It is a question of what that solution looks like, and it really is about doing (these) kinds of studies, and having a set of conversations with all the stakeholders.”

Cahn said the environmental studies under the National Environmental Protection Act will also require a look at environmental justice implications and “how does any solution potentially disproportionally impact communities of color.” A large percentage of Eastwick residents are people of color, she said, and they are already having to deal with environmental issues in addition to flooding, including the two landfills. Clearview landfill is poised for an EPA cleanup, Cahn said. But this is a long-standing situation in which some residents have dealt with not only water, but fear that water was bringing contaminants with it.

“Anything that the Army Corps needs to do, needs to be in coordination with the EPA,” she said.

A combination of approaches may be needed, Cahn said. For residents who have experienced flooding repeatedly and can’t sell their homes, a buy-out may be the best bet, she said.

Cahn said that a Corps solution can’t be the only solution, as it would address catastrophic event flooding, but not other kinds of flooding that happen in other parts of the neighborhood.

At the hearing earlier this week, Neukrug said studies show other flooding is being caused by very local conditions – in cases property by property – and that his department will work to address them. He said it is not a sewer capacity issue, but residents strongly disagreed, saying they see water pouring out of drains during storms.

Residents oppose the Korman apartment plan and the land transfer to the airport, in part because they believe development will exacerbate the flooding problems in their neighborhood. Neukrug and Deputy Mayor Rina Cutler testified that isn’t so – water department regulations would require Korman to improve stormwater management on the property. If Korman’s proposal didn’t, Neukrug said, his department would not allow a building permit to be issued.

It was after the proposed settlement came to light that the zoning bill and land transfer bill were held in committee last June, and Tuesday’s hearing on flooding issues in Eastwick was called for.

Cahn said she is pleased with the water department’s actions – not only approaching the Army Corps, but also conducting flooding surveys and learning more about the water issues in the neighborhood.

But that doesn’t mean the city should move forward with the Korman proposal.

“The Army Corps is at least engaged, so talk of a solution is more than speculative,” she said. “At the same time, there are so many factors involved to make sure that you have a plan, resources and political will from all levels of government. To use this as the carrot to move the Korman Development forward is disingenuous and unfair and unjust.”

Reach the reporter at kgates@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.