Transformation from pumping station to Philly Fringe home begins

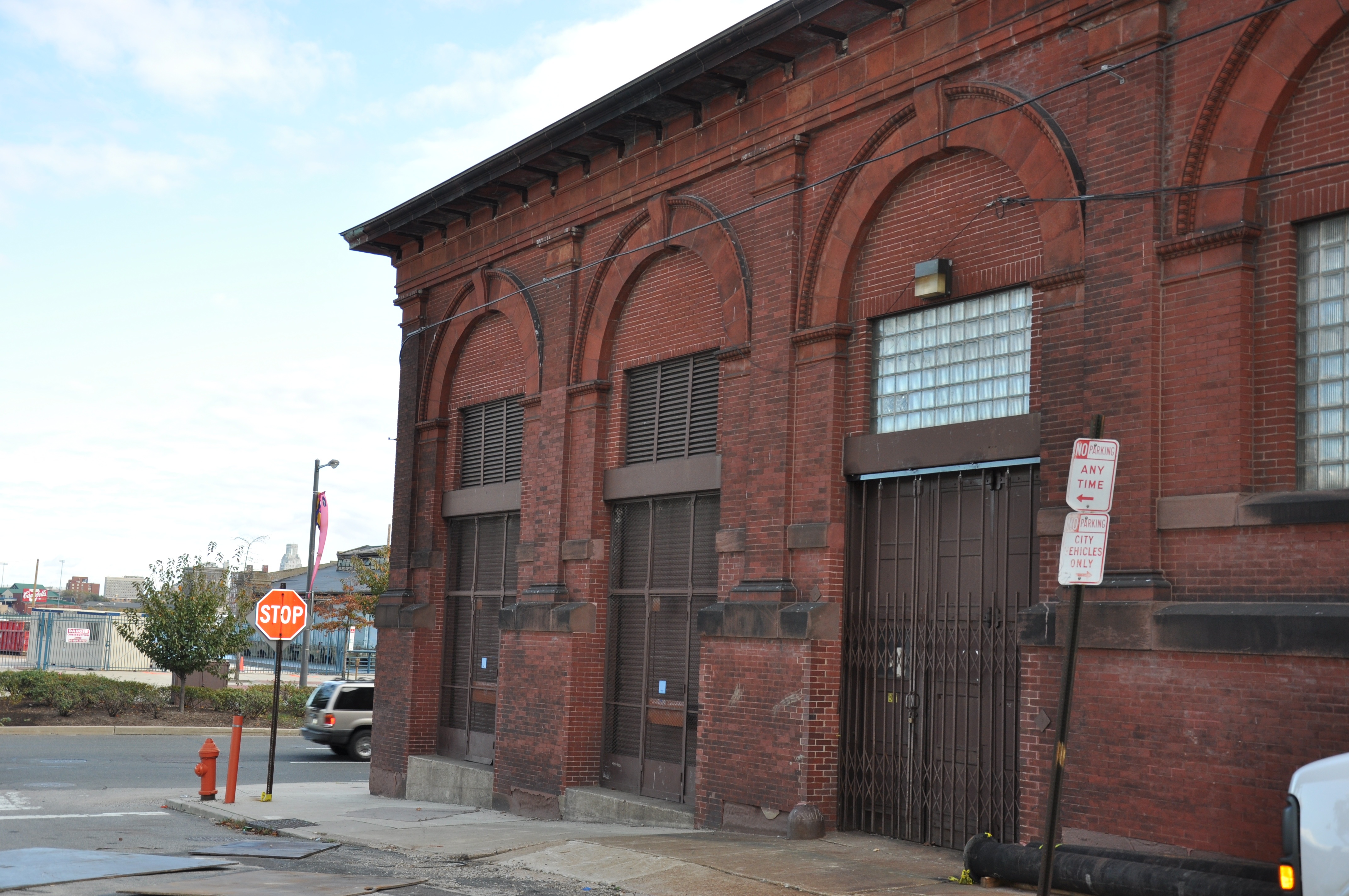

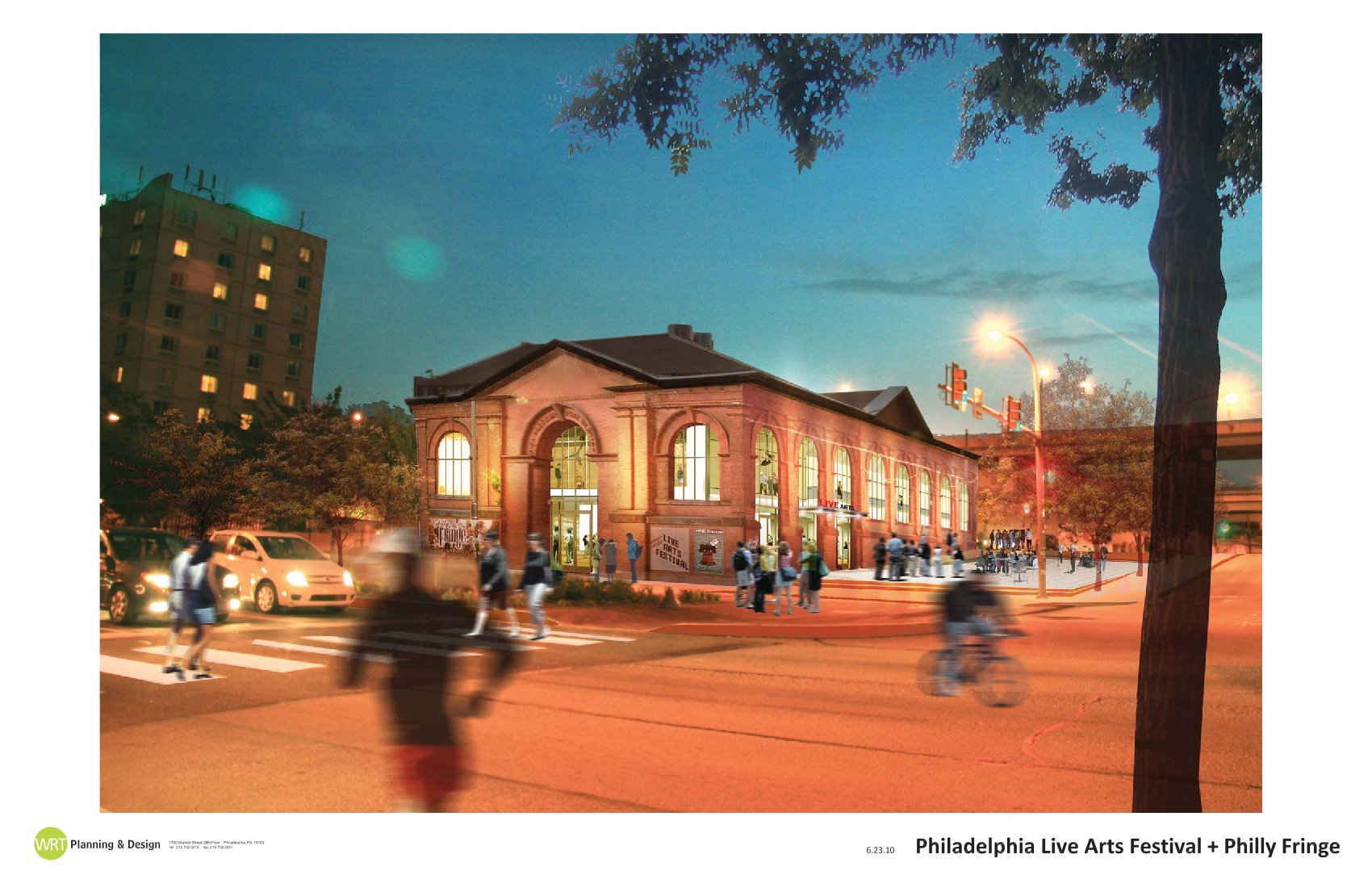

The transformation of a 1903 riverfront pumping station into the future home of Philadelphia Live Arts Festival and Philly Fringe has begun.

The organization best-known for its annual festival began tearing out old pumps and shoring up the brick structure at the corner of Race Street and Columbus Boulevard after hitting a fundraising milestone: 90 percent of the $5.2 million it will take to complete the first phase of construction. Efforts to raise an additional $1.5 million or so are under way, said President and Producing Director Nick Stuccio.

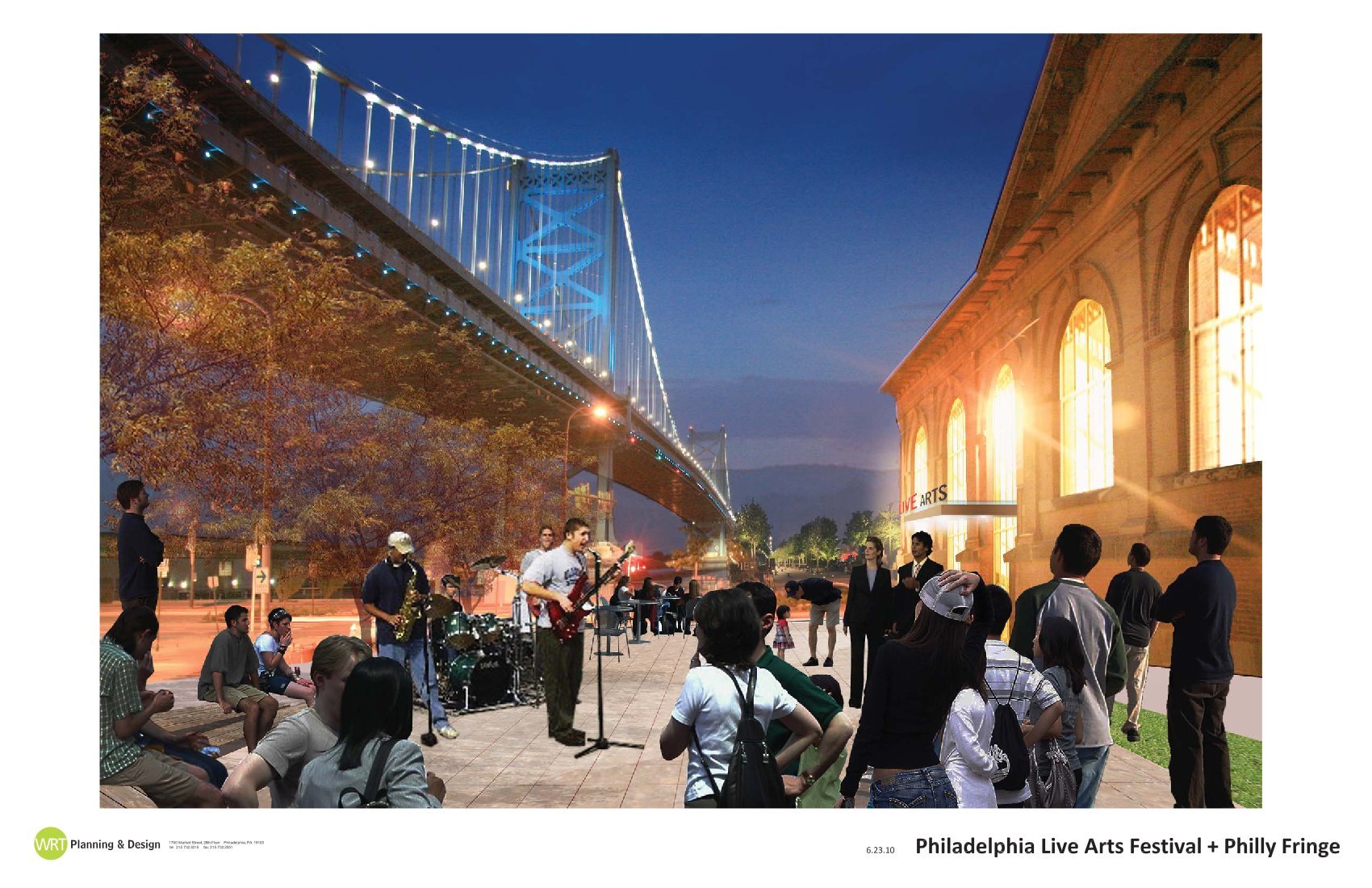

The goal is to have the new 240-seat theater, studio and offices ready for this fall’s Fringe Festival (Sept. 6-21). An indoor restaurant and bar, outdoor plaza space and further building restoration will be completed by late spring 2014, he said. This week’s big project in the 1,500-foot space: Spraying the ceiling with six inches of material designed to both improve acoustics and provide insulation.

The festival, which brings international, contemporary performance art to a huge number of sometimes unusual places around the city each year, won’t change its focus, Stuccio said.

But having a permanent home-base will allow Philadelphia Live Arts and Philly Fringe to become more of a year-round presence in Philadelphia, with regular performances in its new theater, he said. Competition for a slot on the festival roster is fierce he said. More time means more opportunities, especially for local productions and acts, he said. Stuccio sees the possibility of mixed visual and performance arts installations on the waterfront, along the pedestrian and bicycle trail, and even in some of the existing strip-malls.

“A world of possibility opens up,” he said.

Why this building?

“It’s cool as hell!” Stuccio said when asked why his organization chose the red-brick building with big window arches, steel trusses, and a hip roof with gables.

The structure is distinctive looking and historic. But there were some more practical considerations mixed in with the cool stuff, Stuccio said.

The building provides a big, wide-open space with high ceilings and no columns or walls.

It was in excellent shape and “it was zoned appropriately, meaning we could get a liquor license.”

Stuccio says he’s “not some crazy young dude” who wants to host wild gatherings. What he wants is to offer a socializing, gathering space right where performances happen. Before or after a performance, people want to grab a coffee, a drink, a muffin or dinner, he said, and they want to talk about what they’ve experienced or will experience. “For too long, we’ve ceded that to other people,” he said. At the future Philly Fringe, patrons may sometimes even get a chance to discuss the art with the artists, he said.

The price was right: $750,000. “Five years from now, this building would have been out of reach for us,” he said.

And that brings us to location…

“We knew about the frontier of the Delaware Waterfront,” he said, referring to the city’s efforts to revitalize the seven-mile stretch between Oregon and Allegheny avenues with residential, commercial and industrial development and new parks linked by a bike and pedestrian trail.

“We talked about it as a neighborhood on the rise. And here we’re at the base of the (Ben Franklin) bridge, and near the new park, Race Street Pier, between Old City and the waterfront.”

Stuccio said the trail and bike network, the residents and restaurants, and all the activity called for in the master plan would certainly help his organization – in short, the more people, the better, he said.

He also believes Philly Fringe will help push the master plan forward. The performances, restaurant and gathering spaces inside and outside will help draw people from Old City down Race Street and to the waterfront, he said.

Stuccio said Philly Fringe’s re-use of the building is another example of the phenomenon where artists buy or get use of space before a neighborhood pops. The arts often play a key role in making neighborhoods pop, he said. He noted that Philly Fringe used what were then vacant warehouses in Old City from the Fringe’s beginnings in the 1990s, and referenced South Street, where artists moved in when the prospect of highway construction drove prices downward.

Often, artists are displaced when demand drives prices upward, but Stuccio said Philly Fringe will be in its new home for the long haul.

What’s it like in there now?

On a brief tour of the building, filled with both dust and noise on Monday, Stuccio pointed out historical elements, most of which will be kept visible.

There’s a huge pipe within a gulch in the cement floor – part of a back-up pressurization system for the city’s fire hydrants. It could shoot water many stories in the air, he said. The system became redundant when a code change required buildings to have their own fire suppression systems. This will be covered over.

A large crane hanging over the east side of the building will remain in place. It’s too big to be used in moving things around for the theater, he said, but it will be visible from the bar.

The building has many huge, arched windows. Their original shape is still visible, but has been filled in with bricks and glass block. They will be restored.

The walls, for most of their height, are made of light yellow-glazed brick. All but one small area remains covered in paint, but the paint is coming off. Stuccio said the nicks in the glaze will be stabilized, but not repaired. It’s all part of the building’s history, he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.