Penn aims to spur innovation in Lower Schuylkill at South Bank campus

On Thursday the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation and Commerce Department released the Lower Schuylkill Master Plan, a blueprint that aims to put 68% of the city’s vacant, industrial land back to work. The plan envisions an “Innovation District” at the northern end of the Lower Schuylkill, just south of University City, where industrial properties will be reused for new ventures spun off from university research.

At this point most of the “Innovation District” is a mix of underutilized or vacant industrial relics. But there is an early outpost that makes the aspirations for new enterprise in the Lower Schuylkill feel real: The University of Pennsylvania’s South Bank campus, a 23-acre former DuPont property along the Gray’s Ferry Crescent that the university plans to transform into a buzzing hive of technology transfer and product innovation.

The Marshall Labs site, or South Bank as Penn calls it, sits on the eastern side of one of the Schuylkill’s wide turns, between the University Avenue Bridge and Gray’s Ferry Avenue Bridge. It is shockingly close to Penn’s campus, but the gated research park feels like a world apart. In addition to the Gray’s Ferry Crescent, which skirts the site along the river, South Bank’s nearest neighbors are two gas stations and a Waste Management facility.

But this odd spot is a place of tremendous opportunity where Penn is aiming to create robust entrepreneurial campus where research and development tied to the university can be incubated and commercialized.

What Penn is doing at South Bank “goes a long way to help people understand that this really can be a viable place for development and investment,” said Tom Dalfo, PIDC’s Senior Vice President. “Its presence alone helps to give the innovation district some definition and some weight.”

Penn purchased the DuPont Marshall Research Laboratories site for $13 million in 2010; a year after DuPont vacated the site. The prospect of 23 acres of industrial property at the edge of Penn’s campus was a deal too good to pass up.

“It was a perfect opportunity and in the tradition of what Penn has done for many years: To acquire land, and land bank to provide options for future growth. So we will have short-term uses and then longer-term uses over time,” said Anne Papageorge, Penn’s vice president for Facilities and Real Estate Services (FRES) as she and a team from Penn showed me around South Bank this winter.

Our tour began with one of the most compelling spaces at South Bank, – a large loft-like floor in “Building B176” (the engineering culture of DuPont lives on) where huge windows offer skyline views. As we entered, Penn’s Director of Real Estate Development Paul Sehnert quipped, “Where do you find space like this?”

It would be easy to imagine a coworking space or performance venue there, but DuPont built it to house a large lab, and designed the building to carry a massive 700 lbs per square foot of load (six-to-seven times what a normal office building might be designed to carry). It’s one of four buildings targeted for reuse by Penn.

“These are the kinds of resources that universities can use. This could be a location for incubator space, this could be all kinds of functions,” Sehnert said.

For now the uses at South Bank are a fascinating jumble, many driven by needs that can’t be met on Penn’s core campus. Amid the empty lab and office buildings, Penn Transit has its new headquarters (moved from a surface parking lot on Walnut Street where the Krishna P. Singh Center for Nanotechnology is now being built). There are also several spaces rented as storage for the Inn at Penn, Penn bookstore, and Penn Athletics. South Bank is where the air structure from Penn Park comes to hibernate during summer months. It is also where Penn built a “bridge” data center to help absorb the university’s immediate (though interim) needs.

“But these are hardly the reasons why you buy 23 acres,” Craig Carnaroli, Penn’s Executive Vice President recently told me. In the near term, these uses help underwrite the cost of the campus as Penn makes bigger plans to transform South Bank into more of a technology park.

Though there aren’t all that many tenants yet, there is a lot of interest in the South Bank’s varied spaces from academic researchers, startups, as well as local civic and cultural institutions in need of space.

But the ranks of tenants with Penn ties are growing, each demonstrating that the demand for this kind of space is real.

In September Penn Vet’s Working Dog Center opened in a South Bank building, where Dr. Cynthia Otto and her team are training puppies to be police and homeland security dogs.

Not far away there is KMel Robotics, which developed technology for swarming quadrotors (a fleet of small, coordinated, flying drones). KMel’s roots are in robotics research at Penn, and there was space available at South Bank when they received grant funding and needed cheap, basic facilities to work in immediately.

“It’s great for what we’re doing because we have these offices and we have some small testing lab space,” said KMel’s Dan Mellinger of their space at South Bank.

The same story is true for Graphene Frontiers, which grew through Penn’s UPstart program that supports the commercialization of academic research.

“We’ve had a steady stream of prospects coming to us from the Center for Technology Transfer and by and large these entrepreneurs only want a few things. They need the space, they need it tomorrow, they need it on flexible terms and they don’t really care that it’s not pretty,” Paul Sehnert explained as we toured.

Innovation, Sehnert notes, is very much part of the site’s legacy.

“DuPont did some really cutting-edge stuff over here. Sometimes they refer to this thing in the popular press as a paint factory. It hasn’t been a paint factory since the ‘20s. It was a research plant,” Sehnert said. “This is where the stealth coating [for Stealth Bombers] was perfected.”

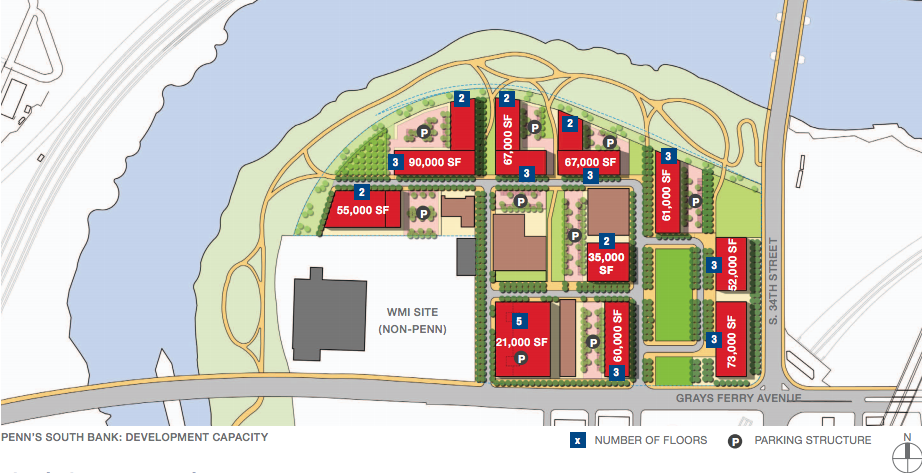

South Bank has several vacant acres ripe for new construction, existing wet and dry lab facilities that could be repurposed, and plenty of scalable space.

One reuse prospect, which FRES is most excited about, is a large lab building close to Gray’s Ferry Avenue. Right now it’s 8,500 square feet of wet labs, cobwebs and no power, but someday it could incubate collaboration between university researchers and one of the region’s life science companies.

“The problem for us is we need a central and transformative thing to really make this stuff go,” said Sehnert as we stood in the dark lab building.

In the near-term Penn hopes to house fledgling companies spun off as commercial enterprises from university research, as well as attract more established companies that value South Bank’s proximity to the minds at Penn. That’s a complex and delicate tenant mix, but one that could prove potent.

That’s part of the reason why the university is concentrating on developing a plan to make South Bank into a more attractive campus for prospective tenants.

In South Bank’s current state, Carnaroli acknowledges, “It’s tough for anyone to be a pioneer even when the price is attractive.”

Earlier this year Penn hired the design firm Wallace, Roberts & Todd (WRT) to develop a plan to improve South Bank’s campus amenities, curb-appeal, and connectivity.

WRT’s plan, which should be complete this fall, is meant to help Penn understand ways to physically improve South Bank, but also help the university refine the vision for its tech-transfer park of the future.

“Tech transfer people need a place to hang out, they need a place to network, they need a presentation room, they need a hub, they need food, coffee,” Sehnert said. None of this exists yet, and it will require serious investment over time.

Right now South Bank is a bland, gated campus with rough edges. But that’s bound to change in the near-term through new pedestrian and bicycle entrances from the Gray’s Ferry Crescent, and an improved streetscape surrounding the site. There is also the matter of working with the city to improve the dreadful intersection of 34th Street and Gray’s Ferry Avenue.

And all of this will balance making upgrades with maintaining affordable space to meet the demands of Penn’s young entrepreneurs.

“I think we’ve got to be patient and take a long-term view,” Carnaroli said. This project is, from Penn’s perspective, about planning for its continued growth and guiding its economic impact on the city and region.

South Bank’s theme may be innovation, but what shape that takes is still very much a work in progress.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.