In Conversation With: Greg Heller on Ed Bacon and his legacy

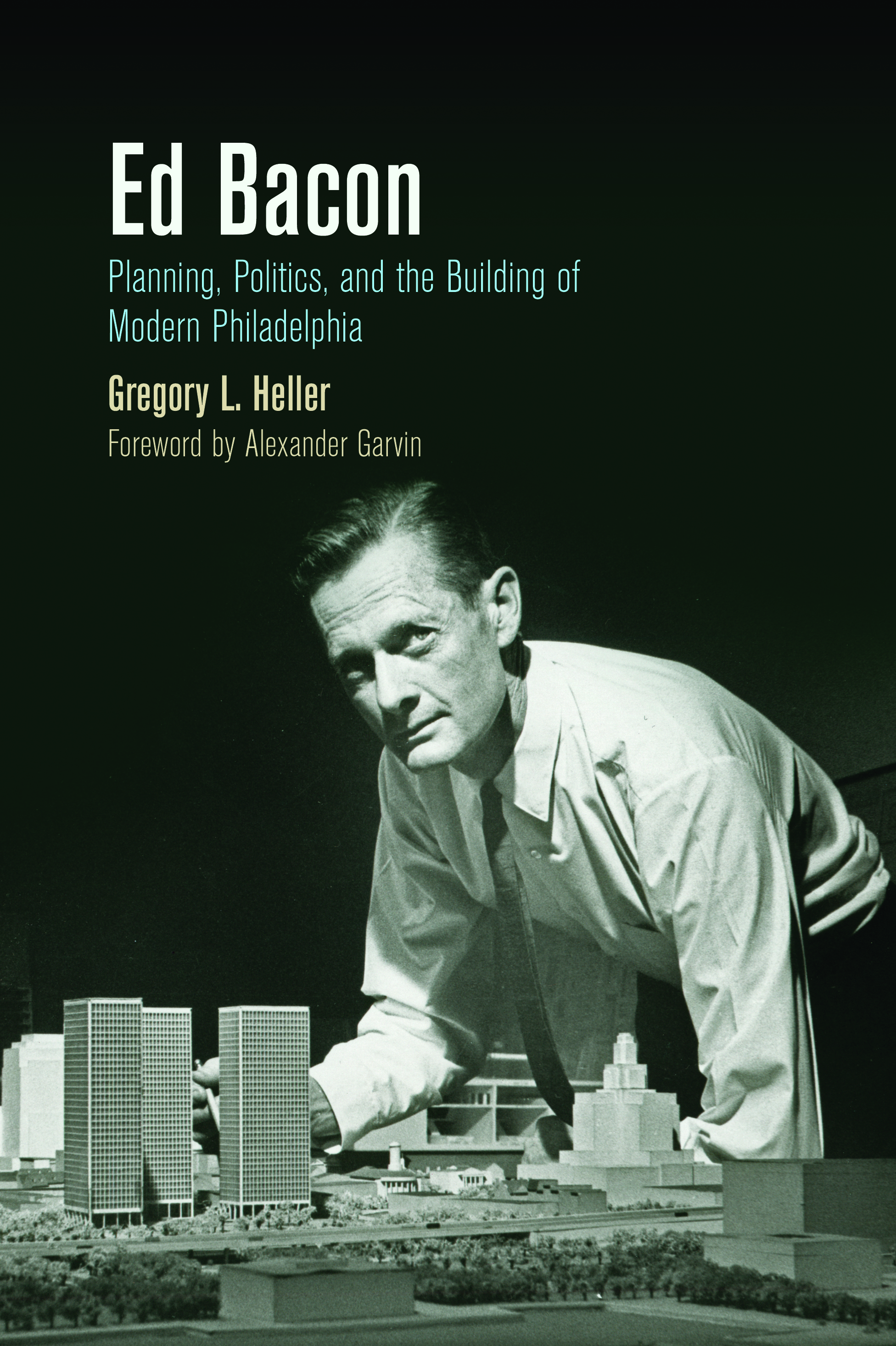

On the eve of the official launch of Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Phiadelphia (University of Penn Press), author Greg Heller chatted with PlanPhilly’s JoAnn Greco about Edmund Bacon and his legacy. The free event is scheduled for Thursday, May 16, at 6:00pm at the Center for Architecture, 1218 Arch St.

PlanPhilly: How did your connection with Ed Bacon come about?

Greg Heller: Between my junior and senior years of college at Wesleyan University — where I created my own major in urban studies — I was an intern at the Philadelphia City Planning Commission. My history professor had been one of Bacon’s students and he suggested that I talk to Bacon. So, I wrote him, he called me and I came over to interview him. I had a tape recorder and a notebook, but when I came in, he said, “What’s all that crap?” He just wanted to chat. We went to lunch at Friday, Saturday, Sunday, and he asked if i would take a year off from school and help him write a memoir. So I wound up working with him, showing up at his house at 9 every day. He was 91 at this point and had incredible endurance. He would take a short nap in the middle of day, but otherwise we’d be working, he’d be writing, we’d do some interviews, into the night. Then, we’d open a bottle of wine.

Your book concentrates on Bacon’s professional life. Talk a little about what he was like personally.

It’s unfortunate that I had to leave that out — maybe someone else will handle it one day! I think he was a really interesting person, beyond his work. He was into art and theater and drama and he threw huge parties that everyone from the architecture and planning world attended, and they’d design costumes and paint murals. It was a way for his artistic personality came out. He really just loved the beauty of the world, and cities especially as place where drama happened. I think that shaped a lot of what you see in his design ideology, which focused on experiences of walking through spaces. His daughter Karen, who is an event planner, told me that she learned that from him — the drama of a space and creating events to accentuate that drama.

But in work, he was a tough customer.

That definitely came through. You didn’t want to get on his bad side. But when you argued back, he loved it. He believed that part of what it is to be human is to have opinions, and I think that he liked that about me. I did get kicked out of his house and get things thrown at me and get called names, though. He was definitely stubborn but he listened really well and there was times when I’d come back the next day and he’d say, ‘you were right, we’re going to go with what you suggested.’ I was 20 or 21 years old and he was valuing my opinions.

To paraphrase Stephen Colbert, did Philadelphia need Bacon — why? was he good for Philly?

Absolutely, he was good for the city. Philadelphia at the time was known as a pretty unprogressive place and the city needed to be activated and to have the eyes of the nation on it in order to develop a more progressive identity. Bacon was instrumental in achieving that. He did get people excited about a new vision for Philadelphia, he was out there trying to sell the idea of Philadelphia on an international stage, with cities like London and Paris and Rome. He brought a lot of attention and money to the city based on his effective marketing approach and he was also able to play an important role behind the scenes in getting projects actually into the pipeline and built. I don’t think that any of the new urban revitalization we’re seeing today would have been possible or at least significant without the work that was done during the urban renewal era.

What were Bacon’s great strengths — and weaknesses?

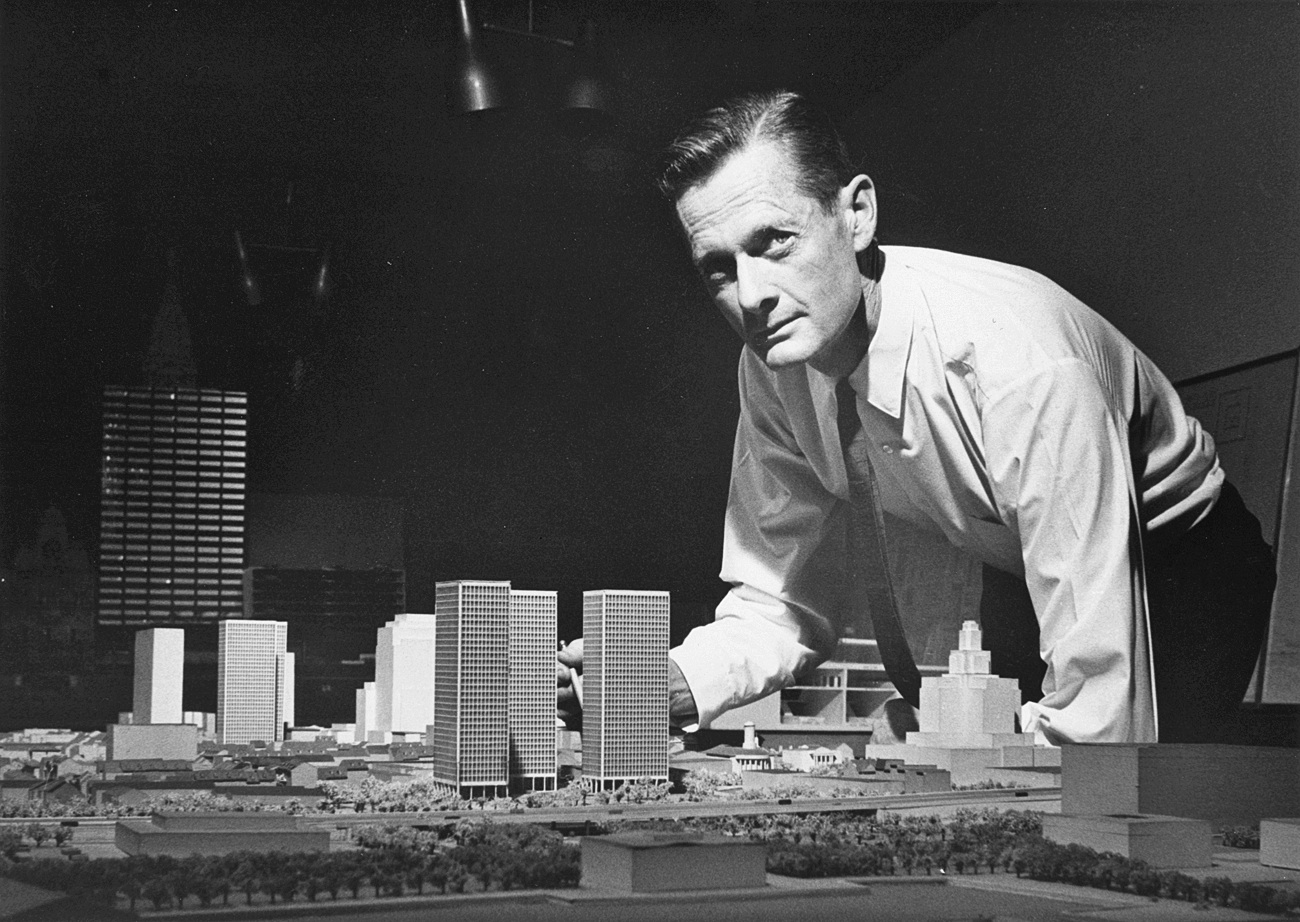

Bacon wanted an approach to urban renewal that was sympathetic to the historic structure. Society Hill was a whole new model, for example. Before, everything would’ve been bulldozed, everyone would’ve been displaced, and everything would’ve been rebuilt. He was also good about public-private partnerships, he was before his time on that. Tearing down the Chinese Wall, for example, was basically Bacon as a public official trying to influence the way that a private company was allowed to redevelop its real estate. He ultimately admitted that the buildings that went up were ugly, but look at where our central business district wound up: there! His idea was very successful, and you can’t access Bacon’s legacy on the architecture of a bunch of individual buildings, because that’s not what he did.

As for weaknesses, he was really bad at talking to neighborhood groups. He believed very strongly in it, he was out there when other officials wouldn’t bother, but he just wasn’t good at it. Part of his personality was to have strong opinions and hope that people would argue back, but those settings are a real power dynamic, they’re not a true conversation.

I liked reading about Saarinen at Cranbrook telling him that form and its social aspects can’t be separated. Do you think is why he made the shift from architecture to planning?

The social aspect is a big part of who he was, I’m hoping people will discover that or rediscover it. He really focused on innovative forms of housing as community design for the underclass: at Cranbrook, In Flint, as head of the Philadelphia Housing Association, a nonprofit afford housing advocacy group, and early on in his tenure at PCPC. It’s a whole part of his legacy that’s been overshadowed.

Any lessons that Philly can learn from Bacon?

He had a really strong belief that people can and should shape the future. I’m seeing that more in Philly today, with neighborhood leaders and others taking the reins and saying ‘I’m going to play an active role.’

I’ve always thought that Bacon would make for a great documentary subject. Since you have so many tapes and documents, is there any interest or possibility of you becoming involved in that?

I donated everything to the University of Pennsylvania archives since I wanted researchers to find everything easily. I’m not interested in doing a documentary myself, but I would love to help with scripting one, actually. In the interest of space and focus, the Penn Press editors had me cut out a lot of stuff from him early and later life to concentrate on the 21 years when he was a planning director. So there’s a lot more to cover in a film or another book, but that’s nothing I’m going to explore further. I’m busy with my own career.

So what, ultimately, is Bacon’s legacy?

The Center for Architecture took over his Foundation a few years ago, and its work includes a student design competition and the Edmund Bacon prize.

How about getting a street or something named after him?

My goal isn’t to create a legacy for Bacon, but that to emphasize that I feel he’s an important case study for understanding how planners can be implementers. He was a big influence for me professionally and i think he shouldn’t be allowed to fall into obscurity. I do think that’s a danger.

He needs a brand or tagline! Something like ‘make no little plans’ or ‘the power broker’.

I made one up– ‘the planner as policy entrepreneur’. He was a great marketer of his ideas.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.