Streetsplainer: Why do the buses stop every block?

Welcome to Streetsplainers, an occasional series of answers to those often overlooked questions about our beleaguered/beloved transportation systems: Just what the heck is that thing in the road? Why on Earth would SEPTA do that? How does that weird doohickey work? E-mail Jim your questions, and he’ll chase down the answers, hopefully in a reliably on-time fashion.

“Why do we stop at EVERY corner?” is one of the more common complaints among younger bus riders. It seems intuitively obvious that stopping more=slower rides, especially when you stop to pick up just one person and end up missing a green light, adding literally hundreds of seconds to your morning commute, seconds that should be spent getting more coffee from the break room and reading PlanPhilly, which you justify by telling your boss it’s “work-related” news, even though you’re a wedding planner and we don’t really cover that kind of thing.

Where was I? Buses? Right, yes, buses: why do they stop at every corner? Wouldn’t it be faster if we skipped a few? It’s not like walking an extra block would kill anyone. Heck, most Philadelphians could afford to walk a bit more.

And reducing the number of stops a bus makes has been shown to speed up trips, reducing travel time on a bunch of L.A. buses 1.3 percent for every 10 percent reduction in the number of stops.

A 1.3 percent reduction in total trip time may not seem like a lot, but over the course of a day it can add up to “another bus”: the collective time saved adds up to allow for another run down the route with the same number of buses. In other words, a route that uses 4 buses to collectively service the line 28 times would now be able to run 29 times.

It also means smaller headways between buses, which make for shorter waits, increased frequency, and more ridership. And all without having to buy more buses.

So, man, seriously, why aren’t we doing this?

Well, kind of like actors, what works in L.A. doesn’t necessarily work in Philadelphia. SEPTA, with assists from the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities and the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, ran a pilot study of six low-cost transit service enhancements – including bus stop consolidation – on the Route 47 bus back in 2011. And the results of that study weren’t that great (you can read it here).

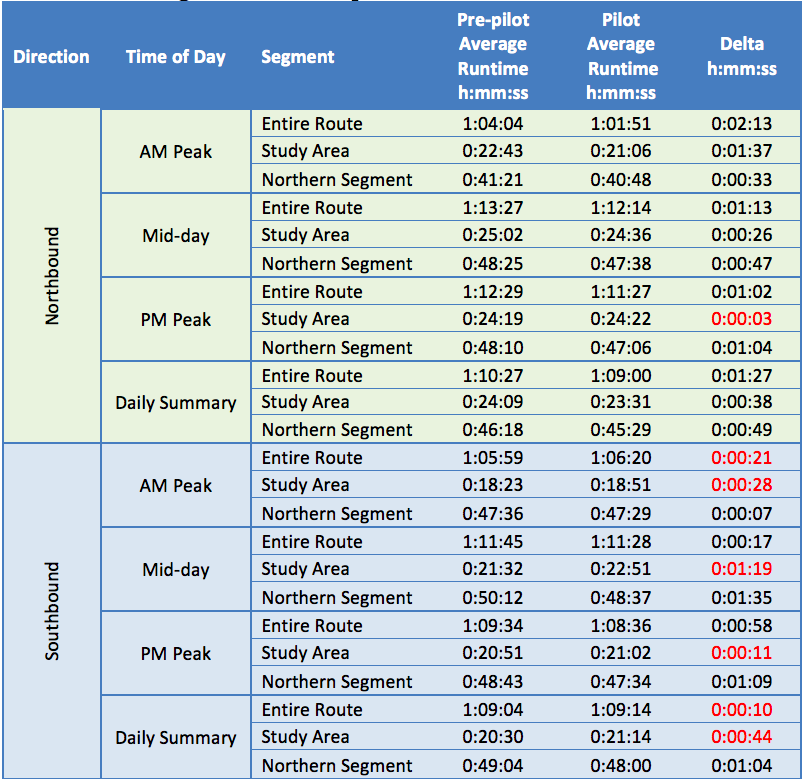

“Overall, runtime in the northbound direction decreased by 1:27 (or roughly 2%), whereas travel in the southbound direction increased by 10 seconds,” the pilot team wrote in a report of their findings. The northbound decrease wasn’t nearly enough to get to “another bus”.

The study’s authors credited headway-based scheduling for almost all of the speed improvement. Headway-based scheduling means schedules simply say “buses come every 10 minutes” instead of listing arrivals at 9:00, 9:10, 9:20,etc., which can sometimes force unexpectedly fast-moving buses to slow down to maintain the schedule.

So, what gives? Why did bus stop consolidation act like local professional basketball teams and perform better in LA compared to Philly?

Stop signs.

You can get rid of all the bus stops you want, but buses are still stopping at every intersection in most parts of this town thanks to stop signs. And that’s particularly true for the section of South Philly where the planners tested bus stop consolidation.

Consolidation doesn’t save much time in the actual getting on or off the bus; passengers who would have gotten on at a consolidated stop will still get on the next one. The time spent literally boarding and alighting usually stays the same, or even worsens a little bit.

Rather, it’s the reduction in the amount of slowing down and accelerating buses need to do where time gets saved.

But if the buses need to slow down for stop signs anyway, then there will be no reduction in travel time. Or, as the report’s authors put it: “stop signs located at every corner minimized the impact of stop consolidation as buses had to continue to stop at every block, even without picking up or letting off passengers. Thus, the bus must still decelerate and accelerate.”

Now, some people may take this as a rallying cry to get rid of four way stop signs on some streets, creating throughways throughout the city.

Traffic habits long forged in the crucible of South Philadelphia streets are not easily broken, and removing stop signs along, say, 7th street to speed north-south traffic would result in too many accidents, as drivers crossing 11th would assume cross traffic would stop. Plus, it would create snarls on easterly and westerly traffic flows. And, with any traffic changes, there would be complaints.

Speaking of complaints, the planners behind the 47 bus pilot heard plenty about the consolidation, although not as many as they had expected. Still, in the end, the removed stops were restored.

That doesn’t mean consolidation can’t work anywhere in Philadelphia – the study’s authors said the 47 route made more sense as a pilot for political rather than practical matters, citing relatively open minded neighbors and district councilpersons. Indeed, the DVRPC recently recommended bus stop consolidation in the form of the Enhanced Bus System proposed for Roosevelt Boulevard.

But stop consolidation’s lack of efficacy, combined with passenger complaints, is why most Philly buses stop at every corner.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.