Two largest land banks in Pennsylvania have been slow getting off the ground

There are some neighborhoods in Pennsylvania cities where half of the properties are blighted or tax-delinquent or both. Between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, there are about 60,000 such properties. But getting them into the hands of new owners who can make them useful for the neighborhood again has been difficult. Enter a 2012 state law that allows cities to quickly acquire properties, eliminate back taxes and get them to new owners. But in reality, there has been little progress.

Pittsburgh

The Pittsburgh Land Bank’s full board met for the first time on a late-summer afternoon in August. Councilman Ricky Burgess, chairman of the board, called it a historic moment and applause echoed in the tall-celling Council chambers as he called the meeting to order.

They have their work cut out for them.

The interim board, named in April 2014, when the mayor signed the ordinance creating a Pittsburgh land bank into law, was supposed to have already drafted policies and procedures. They were also supposed to have come up with a strategic plan by April 2015. Neither of those things has happened.

For the full story, head on over to Keystone Crossroads.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Two largest land banks in Pennsylvania have been slow getting off the ground

Listen

Vacant lots on the 2100 block of North 9th Street in Philadelphia, near Temple University. Eighty percent of the block's properties were tax-delinquent. (Jared Brey/PlanPhilly)

The promise of Pennsylvania’s land banks law — that it would help cities quickly turn blighted or vacant properties into good neighbors — is having trouble finding its way out of the board room.

UPDATED: Oct. 7, 2015

There are some neighborhoods in Pennsylvania cities where half of the properties are blighted or tax-delinquent or both. Between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, there are about 60,000 such properties. But getting them into the hands of new owners who can make them useful for the neighborhood again has been difficult. Enter a 2012 state law that allows cities to quickly acquire properties, eliminate back taxes and get them to new owners. But in reality, there has been little progress.

Pittsburgh

The Pittsburgh Land Bank’s full board met for the first time on a late-summer afternoon in August. Councilman Ricky Burgess, chairman of the board, called it a historic moment and applause echoed in the tall-ceiling Council chambers as he called the meeting to order.

They have their work cut out for them.

The interim board, named in April 2014, when the mayor signed the ordinance creating a Pittsburgh land bank into law, was supposed to have already drafted policies and procedures. They were also supposed to have come up with a strategic plan by April 2015. Neither of those things has happened.

“One of the problems was that the interim board had difficulty doing its jobs,” said Ricky Burgess after the meeting. “In fact, it never did do its job.”

So, the newly seated board is now catching up.

By September’s meeting they hope to have a draft of bylaws and to select a fiduciary. Then, they’ll have to come up with a strategic plan and policies and procedures, a process for which they plan to hire contractors. The latter will have to go through five community meetings before the board can finalize everything.

While the board is finally getting to work, there are other holdups.

The city, which owns about 11,000 parcels of land (there are 20,000 tax delinquent properties in the city, some of them privately owned), will transfer some of its holdings to the land bank. But it hasn’t yet figured out which ones.

“We’ve intentionally delayed this,” said Pittsburgh Mayor’s Chief of Staff, Kevin Acklin. “We could easily have the land bank up and operating but don’t yet have it fixed in terms of how we convey properties to them.”

Acklin said the land bank is just one piece of a larger re-evaluation of how Pittsburgh should manage vacant properties as the city grows and changes.

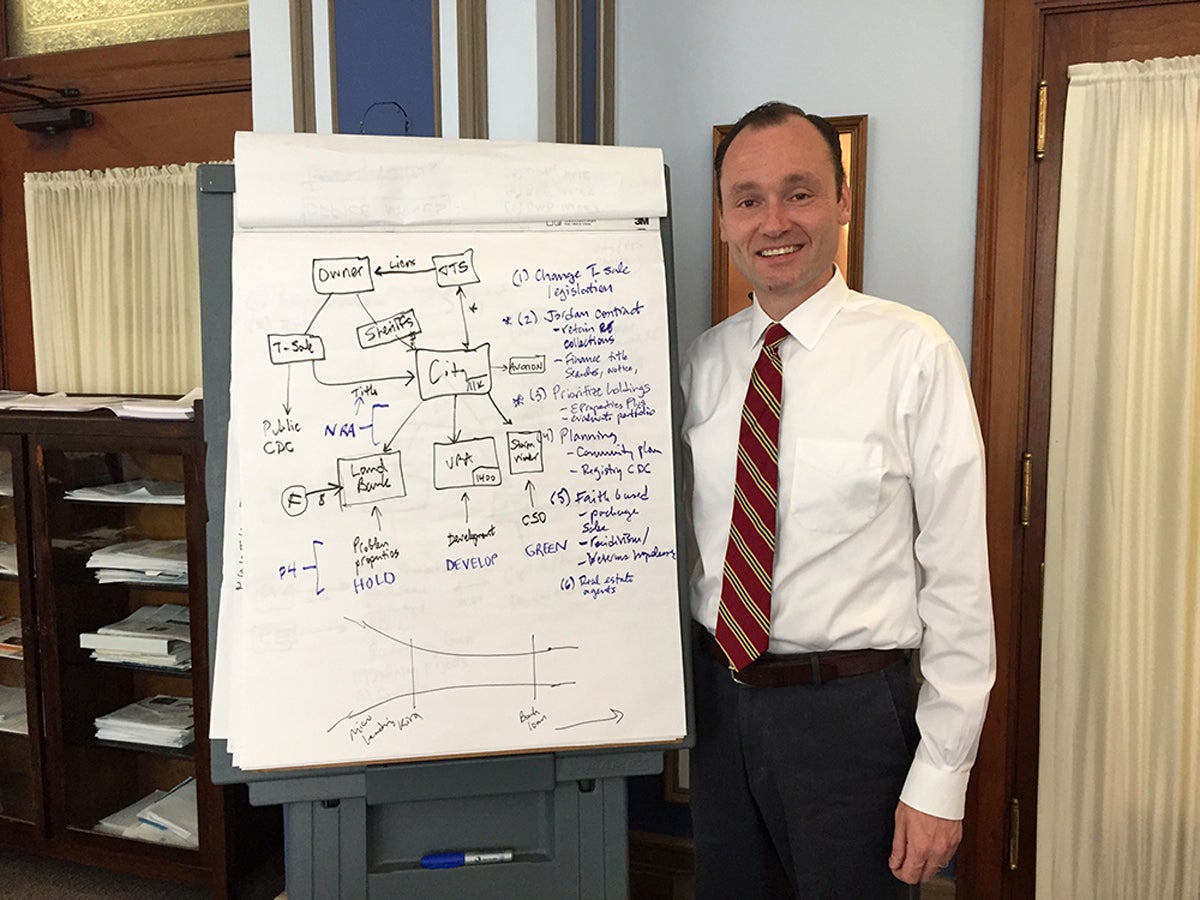

A giant notepad propped up on a stand is a centerpiece in his office. The page is covered with arrows and boxes, a schematic of how the city disposes of land now and the three priorities the city has for its land going forward. In the chart, some parcels go to the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), which focuses on growing the tax base. Some parcels become part of the city’s green infrastructure. And some go in the land bank for community-driven development. But which properties go where?

Kevin Acklin in his office, with a chart showing how the city is rethinking its land disposition process. (Irina Zhorov/WESA)

Currently, individual, siloed agencies claim the parcels they want in an uncoordinated process. But those agencies have started meeting. Kyra Straussman, with the URA, said that will ultimately benefit the city. Pittsburgh has lost half of its population, and it’s the first time the city is thinking strategically about what to do with all of the vacant properties.

“We’re talking about the land,” said Straussman. “And I think making sure that you’re handling it with coherent policies that meet community demands, that are strong for the city as a future city, not just at the present moment, you want to take the time to get it right.”

Burgess, the board chairman, wants to have an operational land bank by January. It’s unclear if the city will have its process sorted out by then. Even if it does, it could take another 18 months to prepare the first batch of properties for resale.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia’s City Council has been talking about creating a land bank for years, since well before the state law even passed. It finally adopted legislation at the end of 2013. Now, the land bank is incorporated, it has a permanent board, and it has a strategic plan.

One thing it still doesn’t have, though, is land.

That’s a source of stress for Barbara Hill-Cisse, a West Kensington resident who’s been trying to acquire the vacant lot next to her house for the last seven years.

“I’ve had neighbors try to use it for trash and scrap metal and to fix cars,” she said.

At one point, Hill-Cisse won the property as the only bidder at a sheriff sale auction. She paid a deposit, but thought she had more time to pay off the balance, after 30 days she lost the property and her deposit. Now it’s going back through the sheriff sale process again.

“I’m just in limbo,” she said. “I’m just expecting somebody to come with, I don’t know what, a sign, knock it down, bulldozer, build something. I don’t even know what’s going on right now.”

Hill-Cisse has been taking care of the lot since a house was torn down there 10 years ago. She hoped the land bank would put an end to the ordeal once and for all.

And maybe it will.

But John Carpenter, the deputy director of the new agency, said everyone expected it would take a while to get rolling.

“We knew there were a lot of things we needed to do before we could get the land bank up and running,” Carpenter said. “The biggest, first one was just getting the strategic plan underway. That was almost a year’s worth of work.”

The strategic plan lays out policies for how the land bank will get properties into the right hands. It also guides how land should be used. Carpenter says the agency is now working on cleaning up deeds for vacant properties and talking with council members about which sites should be transferred into the land bank first. It’s also in the middle of creating a policy for acquiring new land that’s privately owned, vacant, and tax-delinquent.

According to the strategic plan, there are 32,000 vacant properties in Philadelphia, and 8,000 of those are publicly owned. Some estimates put the total number of vacant properties closer to 40,000. Only 10 percent of vacant properties have some kind of structure, according to the strategic plan.

But the biggest obstacle so far is labor negotiations. The land bank is going to be staffed by four separate city agencies with four different unions. One of those unions, representing the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation, is holding out for a better contract. The city won’t say what the sticking points are.

[Update: The Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation has reached a labor agreement with a bargaining unit representing 31 of its employees, the agency announced on October 6th. The agreement is the last of four that were needed for the Philadelphia Land Bank to become fully operational.]

“We’ve made progress, but it’s been slow,” said Michael Koonce, the director of both the land bank and of PHDC. “I’d like to speed it up, I would have liked to have seen it completed six or eight months ago, but it’s a process.”

Councilwoman María Quiñones-Sánchez is well acquainted with delays. She sponsored the land bank legislation in City Council, and shepherded it through a tortured amendment process in committee. Her district has one of the highest concentrations of vacant land in Philadelphia.

“We’re all frustrated in how difficult it is and how complex, given union negotiations and contracts and the different agencies involved, how this all comes together,” Sánchez said.

Sanchez hopes the labor negotiations will wrap up soon and that the land bank will start turning over properties.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.