Mayoral Mobility: How Philly got around, got along, and got by under Nutter

PlanPhilly is taking a look back at Philadelphia during the Nutter Years and down the road at what to expect from the Kenney administration. Jim Saksa offers the next installment in this series with an appraisal of Nutter’s record on transportation matters.

The prevailing narrative explaining Michael Nutter’s eight years in office goes a little something like this: bright, hardworking, ethics-driven councilman takes office with lofty expectations. Aided by a sharp staff of technocrats, the City makes improvements on his watch—reduced crime, new parks, improved finances, cleaner city government, growing population, glowing national press—but on a few large initiatives (reforming city pensions, selling PGW, a soda tax) Nutter was stymied by his blunt, my-way-or-the-highway attitude.

But a close read of one policy area—transportation—largely flips that narrative on its head. Here, Nutter preferred incremental improvements and planning over revolutionary ideas and chasing megaprojects. And on most issues involving how Philadelphians get around town, everyone got along during Nutter’s tenure; a marked departure from how John Street’s administration handled street issues.

After eight years in office, Nutter leaves behind a more collaborative spirit among transportation-related agencies, stronger footing for major projects going forward, and higher expectations among residents for better mobility and improved transportation infrastructure.

LESS ROAD RAGE

“I can tell you, [SEPTA’s] relationship with the city really improved under Mayor Nutter,” said Joe Casey, the transit authority’s recently-retired general manager.

“I’ve been here 34 years and I’ve had a lot of dealings with City Council or the mayor’s office and it wasn’t always pleasant.”

Casey’s tenure heading SEPTA mirrored Nutter’s as mayor almost to the day, and he had nothing but praise for improved SEPTA-City relations under Nutter. Over the years, public spats between SEPTA and the city became increasingly rare; today, they’re practically non-existent.

“The cooperation between SEPTA and the City—whether it’s [Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities] or Streets Department—vastly improved improved as far as getting things done,” Casey said.

The importance of cooperation was a point Rina Cutler, Nutter’s Deputy Mayor for Transportation and Utilities, also highlighted: “Part of Mayor Nutter’s legacy [will be] bringing lots of people to the table that didn’t have great relationships with the city and creating an environment where people want to solve problems.”

Nutter created the Cutler-led Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities (MOTU) to improve interagency coordination on infrastructure projects and to help plan long-range projects that don’t neatly align with any one agency’s traditional jurisdiction. MOTU led the Transit First Committee, which brought together city planners, SEPTA, and other departments to work on improving transit service. Critically, the committee shared political cover on projects that could create controversy, like bus stop consolidation, which invariably upsets some riders who have their nearest stop removed.

“We created, over the course of the Nutter Administration, a really good working group of folks who would look at the problem and instead of saying, “no, that’s not my problem,” would contribute to the solution,” said Cutler.

“The legacy of MOTU is really about a holistic view of transportation and infrastructure, a focus on how transportation translates from everything from mobility to health, to greater neighborhoods, to great designs, to great public spaces.”

Something as straightforward as fixing a subway station’s leaky ceiling can involve several government agencies and private entities: SEPTA, the Streets Department, maybe PennDOT, the Water Department, any utilities in the area, local property owners and perhaps a council person or two. Getting everyone to work together is no small feat.

That collaborative environment also bore fruit when it came to public funding. MOTU helped Philadelphia nab federal funding for infrastructure projects, to the tune of $83 million in Transportation Investments Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation. The competitive grants started as a stimulus program aimed at relatively small—usually under $100 million—multi-modal transportation projects.

Philadelphia has been the only city to win a TIGER grant in every year of the program, using those funds to help pay for new recreational trails, the renovation of Dilworth Park, transit signal upgrades, and overhauled SEPTA infrastructure.

Despite successes in securing TIGER funds, Philadelphia has not been in the business of making major infrastructure investments. Besides maintenance projects like the rehabilitation of I-95, Philadelphia hasn’t seen a transformative transportation project completed since the construction of I-95, says Vukan Vuchic, the UPS Foundation Professor Emeritus of Transportation Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Philadelphia is one of the cities that is looking at the transportation problems and trying to repair them in gradual improvements,” said Vuchic. To him, Philadelphia’s slow and steady progress won’t win the race; major improvements will keep the city economically competitive in the coming decades.

Progress on the city’s transportation needs has been so gradual that some of the administration’s most significant accomplishments aren’t even physical, they’re plans.

Nutter elevated city planning after years of neglect during previous administrations. Under Nutter, the city released a citywide comprehensive plan in 2011, and on transportation matters, Philadelphia’s first Pedestrian and Bicycle Plan in 2012, the Complete Streets Handbook in 2013, the Green Streets Design Manual, and the Philadelphia Trail Master Plan in 2014.

Infrastructure projects are slow moving, and most transportation projects begin as part of some plan or another. Conceptual plans lead to feasibility studies, environmental and economic impact analysis, funding rounds, and design processes. And then, if you can find the money, construction. Each of those steps can take anywhere from a few months to a few years. It adds up.

Planning isn’t politically expedient, but without plans in place, it’s almost impossible to capitalize upon the rare instances that unexpected funds from external sources become available.

Besides $83 million in TIGER grants, Philadelphia received over $300 million from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), most of it in 2008 and 2009 for bridge and highway repairs and towards SEPTA’s purchase of new hybrid buses. Those were pretty much the only “shovel-ready” projects on the books. None of it went towards a major project to fix one of the region’s persistent transportation problems, like traffic on the Schuylkill Expressway, or to lay the groundwork for the city’s growth, such as expanding the rail transit system. The City of Philadelphia itself didn’t have any real plans ready to go—no priorities for what the city should tackle next if money became available.

In other cities, stimulus funds were put to work on those kinds of transformative infrastructure projects. Since 2009, transportation writer Yonah Freemark has compiled lists of new transit construction across North America, listing all of the new commuter rail lines, bus rapid transit systems, and trolleys being built in cities like Boston, Detroit, New York, Los Angeles, St. Louis and Las Vegas. But not Philadelphia.

The American streetcar has been reborn: More than ten cities have built or are building brand new trolley lines, spurring economic development along the proposed routes and employing thousands of union laborers. In Dallas, stimulus funds and municipal bonds paid for capping a major highway running through the city’s heart with a new park, repairing a long fissure in the neighborhood fabric. In Philadelphia, we missed the chance to cap more of the Vine Street Expressway.

THERE’S MORE TO (A ROAD’S FUNCTIONAL) LIFE THAN JUST MONEY

Philadelphia’s inability to expand its transportation networks or improve mobility frequently gets blamed on money, or the lack thereof. Nutter entered office in a recession. Tax revenues were plummeting and the city had to cut costs left and right. Who can justify spending money on fixing traffic bottlenecks when you’re closing libraries?

But saying that there wasn’t enough money doesn’t fully explain it. After all, the same recession that hit Philadelphia hit the rest of the nation, yet other cities managed to leverage stimulus funds into major projects.

The recession primarily affected the city’s operating budget. But the capital budget—where funds for new construction and major renovations comes from—is separate. In terms of the city’s capital funds, 2008 and 2009 were boom times thanks to free-flowing stimulus dollars. But that money largely dried up by 2010.

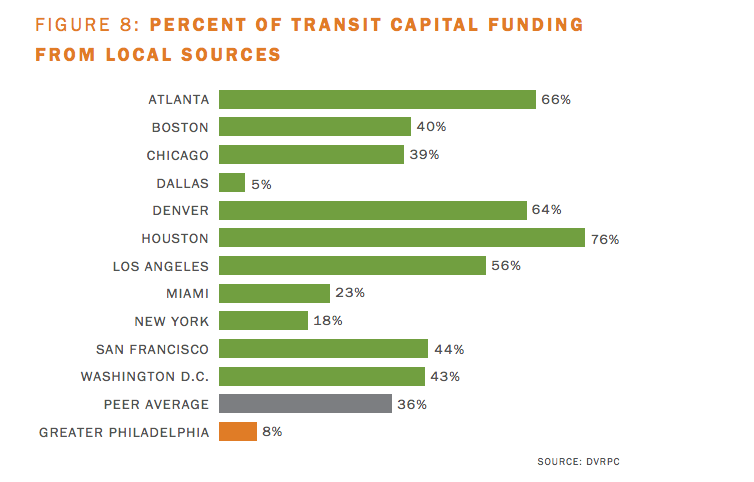

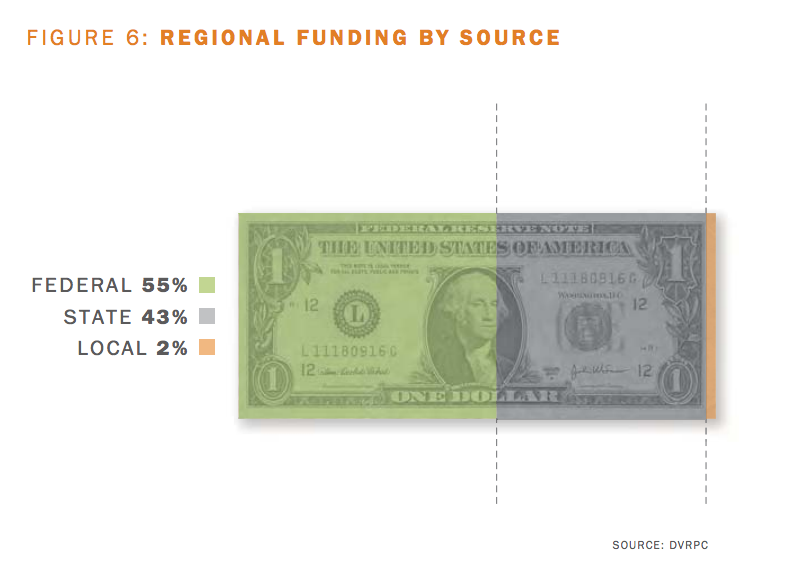

Compared to other large cities, Philadelphia depends heavily on state and federal funds for transportation projects. While the city relies on sources beyond its own tax revenues, that doesn’t necessarily mean it couldn’t undertake significant capital projects. Elsewhere, cities leveraged stimulus funds and floated municipal bonds, taking advantage of historically low interest rates to grow their transportation systems.

When Nutter took office, the federal funds rate was 4.25 percent. By the end of his first year, it would be zero, where it would remain for almost the entirety of his administration. These low rates, which have helped fuel the city’s private-sector construction boom, represented a massive, yet missed, opportunity to improve the city’s transportation network.

But Nutter can’t be blamed, at least not entirely, for squandering this opportunity.

When Nutter took office, the city’s general obligation credit rating was shaky, despite budget surpluses between 2005 and 2007. The recession didn’t help; tax revenues dropped hard. In 2010, Moody’s downgraded Philadelphia’s rating.

Cities that entered the recession on better financial footing were able to take advantage of the lower interest rates and the ARRA’s Build America Bonds program to finance new construction; cities with poor credit ratings like Philadelphia couldn’t actually afford more debt, even with the Fed’s rates so low.

To its credit, the Nutter administration managed to rebuild the city’s finances, but it took years. Since 2013, the city’s finances have been relatively healthy.

Transportation funding saw another boost when Harrisburg passed Act 89, a statewide fuel tax that boosted statewide transportation funding $331 million in 2014 and over $500 million in 2015. In Philadelphia, that meant more money for state-owned highway and street repairs and a lot more money for SEPTA.

EXPECT DETOURS: WHO’S DRIVING DECISIONS ANYWAY?

While money constrained infrastructure spending during most of Nutter’s terms, Philadelphia now seems poised for investment. But where other mayors might have launched a legacy project, like Chicago’s Mayor Richard M. Daley did when he capped rail yards to build Millennium Park, Nutter left office without really leaving his mark on the streetscape.

Vuchic blames this on a lack of vision: “We are still missing a strong picture of the future—what do we want Philadelphia to look like?”

Providing that strong vision for the city’s future is one of the few things Philadelphia’s mayor can actually do in terms of transportation. The mayor of Philadelphia lacks the kind formal authority over transportation decisions enjoyed by some peers in other cities.

The mayor gets to pick just two of SEPTA’s fifteen board members; he gets zero representatives on the DRPA and PATCO boards. PennDOT controls almost all of the city’s major thoroughfares. New federal regulations requiring improved curb ramps for the disabled eats up 65 percent of the city’s repaving budget. On the rest of Philly’s streets, city council has a say on issues like on-street parking regulations, and since 2012, whether a bike lane can replace a travel lane.

For the most part, the decision-making power over any single transportation matter rests somewhere other than the Mayor’s office, and is often fragmented across different agencies at every level of government: local, regional, state and federal. Even a relatively inexpensive project, like converting the Manayunk Bridge into a recreational trail, involved fifteen different offices.

Each entity has its own organizational mission, distinct from the others. It’s tough enough to coordinate across agencies when they readily agree on an issue; it becomes more difficult when those agencies don’t consider the others’ problems to be any of their concern.

That diffuse control limits the mayor’s ability to shape transportation policies, at least directly. Indirectly, the mayor can exert influence by facilitating the kind of inter-agency coordination MOTU provided on various infrastructure projects.

But Nutter didn’t really utilize the mayor’s other informal power over transportation: the ability to articulate and promote a vision for the city’s future through the bully pulpit.

Consider the example of I-95’s reconstruction throughout Philadelphia. That long-expected, multi-phase and multi-year rebuild, currently underway in the River Wards, presented an opportunity to rethink the highway’s interaction with the neighborhoods it runs through. Planners and designers dreamed of burying sections of the 10-lane highway, Big Dig style, and transforming Delaware Avenue, thereby reconnecting the city to the Delaware waterfront. But the Nutter administration quickly dismissed that idea as totally unrealistic. Instead, the city’s looking at a smaller cap, just between Chestnut to Walnut Streets. PennDOT is fine with a pared down project—the state authority has plenty of other highways and bridges to rebuild and its mission is facilitating the flow of goods and people, not revitalizing a moribund waterfront.

Instead, most of the expansions and improvements to Philadelphia’s transportation network over the last eight years have been relatively small, focusing on modest improvements to pedestrian and bicyclist safety. The city added some bike lanes—about 6 miles a year, according to the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia. Indego launched in 2015, albeit years after most other cities introduced their bike share systems. Philadelphia upgraded some traffic signals, rebuilt the South Street Bridge, built a bunch of cool trails, and resurfaced some roads – but not enough to keep up with the backlog.

Despite the relatively modest scale of these achievements, Nutter administration’s humble approach to transportation has been met with largely positive marks.

“A lot has been done,” says Sarah Clark Stuart, interim director of the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia.*

“Progressive bicycle and pedestrian policies, and thinking around making the city streets safer for all users, have been baked into the city’s way of doing business.… That’s a result of the mayor deciding to make the city’s transportation network function and work better for bicyclists and pedestrians.”

David Curtis, co-founder of urbanist PAC 5th Square, gave Nutter a B+ on transportation. That’s the same grade Councilman Bill Greenlee gave the last administration. Despite his disappointment over the dearth of dramatic progress, Vuchic had mostly positive things to say about the last eight years.

The Nutter administration’s measured aspirations on transportation issues probably served it well, politically. Major infrastructure projects are often high risk, no reward for politicians. By their very nature, they take years to finish, all but guaranteeing that the payoff happens long after elected official leaves office. But all of the political pain hits immediately: the construction detours, cost overruns, and budget squeezes.

COMING FULL (TRAFFIC) CIRCLE

It’s the fight over bike lanes—frequently and lazily cast as a symbol of gentrification—where the familiar narrative about Nutter returns to haunt transportation issues.

City Council took away the administration’s sole discretion over bike lanes, and inserted itself in the approval process for any lane configuration changes, because “the community should be involved in the decision somehow,” according to the bike lane bill’s sponsor, Councilman Bill Greenlee.

It’s unlikely that City Council would have gone through the legislative trouble of inserting itself into the sort of traffic engineering process that other cities consistently leave to technocrats if it weren’t for council’s testy relationship with Nutter.

“Sometimes, I think there was, in this [Nutter’s] administration, a sort of rush to sort of say, put bike lanes everywhere,” says Greenlee. He adds, “I’m not saying we would have been against it,” but Greenlee pointed towards the buffered bike lanes on Spruce and Pine streets as an example where more community input was needed.

Philadelphia’s new mayor, Jim Kenney, doesn’t face the litany of problems Nutter did when he first took office. For one, his relationship with council is largely considered a strength, not a liability. Nutter put the city’s financial house in order and set plenty of plans into motion. Interest rates are still low at 0.25 percent, but won’t stay that way for long: The Fed expects to raise rates to 4 percent by 2018.

While Kenney is doing away with Nutter’s system of deputy mayors, he’ll likely keep MOTU around in some form or another. The name may change, but the functions will stay.

Will Kenney stick out his neck on transportation issues? Candidate Kenney promised a commitment to complete streets and vision zero—both arenas require significant compromise and change. Will he exert political capital where Nutter displayed uncharacteristic timidity? So far, Kenney’s left the bold policy proposals to Council President Darrell Clarke, who declined to speak with PlanPhilly for this article.

Time will be the test. Over the next decade, the region will face some big transportation decisions. Should any of I-95 be capped, if so, by how much? How will we choose if SEPTA’s high speed line should extend to King of Prussia, or if the Broad Street Line should reach the Navy Yard? (There isn’t money for both.) Is capping the rail yards north of 30th Street Station worth the probable displacement of low-and moderate-income residents in Mantua and Powelton Village? Will Roosevelt Boulevard finally get some form of high-capacity, faster mass transit?

The Nutter years left Philadelphia with a solid foundation to build something momentous. To build upon that foundation, Kenney will need to listen to, and then harmonize, discordant positions to unify around a clear articulation for the region’s future.

Failing to lead in this arena resigns Philadelphia to the same kinds of gains achieved under Nutter, but not the projects that transform the region by connecting people to jobs, ensuring more equitable transportation access, or capitalizing on existing assets for development – the kind of legacy-building projects Nutter didn’t realize. On those big-ticket items, it’s up to the mayor to speak up on behalf of the city, because no one else can.

*Disclosure: Sarah Clark Stuart sits on PlanPhilly’s Advisory Board.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.