Resurrecting Mount Moriah Cemetery’s gatehouse

For more than five years, a group of volunteers and preservationists has been slowly bringing the historic Mount Moriah Cemetery in Southwest Philadelphia back from oblivion.

Established in 1855, the then-rural cemetery grew from its original 54 acres to 380, making it of the largest burial grounds in Pennsylvania. Its 80,000 graves include veterans of every American war from the Revolution to the Korean Conflict; blue flags mark the final resting places of 22 Medal of Honor winners.

But the cemetery, which runs along Cobbs Creek and crosses from rowhouse neighborhoods in Southwest Philadelphia to suburban Yeadon, suffered years of neglect by its former owners. Gravestones vanished beneath a tangle of knotweed, overgrown brush, untended trees, vandalism and dumping.

Descendants and neighbors, students and researchers, and others who comprise the Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery have been working since 2011 to clear the landscape, restore the stones, and even give names to long-unknown soldiers.

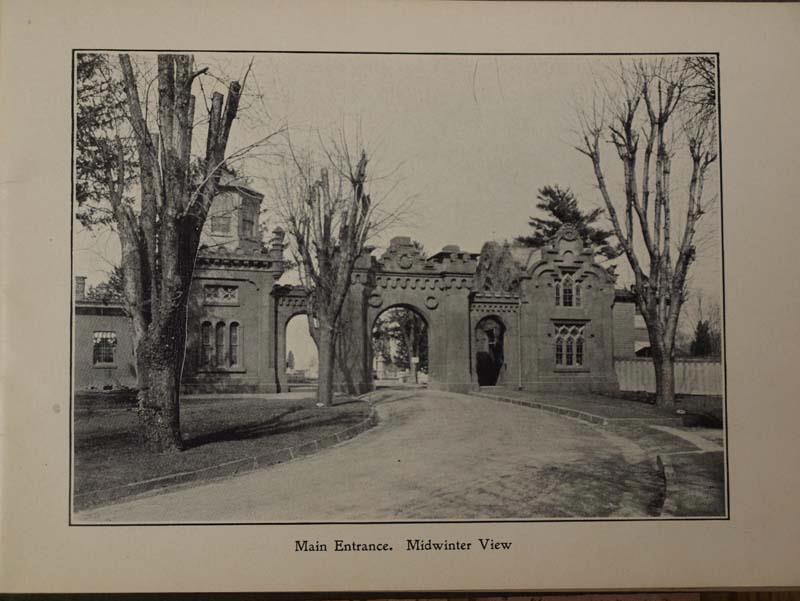

Their work is far from done, and their most immediate concern over the past year has been the crumbling symbol of Mount Moriah — its grand, brownstone gatehouse. Parts of the original building have been consumed by fire, and other sections have deteriorated and collapsed over the years. More pieces of the brownstone veneer crack and fall off each season. Supporting walls came down after a storm last August, and portions of the façade are now listing forward.

“I’m amazed the building made it through the winter,” Aaron Wunsch, an architectural historian and an assistant professor in the University of Pennsylvania’s graduate program in historic preservation who has consulted with the Friends, said last week. “One solid storm will bring that thing down, and the game is over.”

But a plan and funding to stabilize the gatehouse are in place, said Brian Abernathy, president of the Mount Moriah Cemetery Preservation Corporation, the organization established last fall by the city of Philadelphia and the courts to oversee receivership of the cemetery property. The cemetery had been owned by a partnership called the Mount Moriah Cemetery Association until its last member died and it was declared defunct in 2011, the year the Friends group was incorporated.

The Preservation Corporation has finalized drawings from an engineer and expects to hire a contractor very shortly to begin the stabilization of the building, which is on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places and has been deemed eligible for the National Register.

“We’re going to make sure it doesn’t fall down,” Abernathy said. “We’re not going to repair it, but we’ll make sure it doesn’t deteriorate any further than it has and that we don’t lose the structure completely.”

A working-class model

The gatehouse was designed by Stephen Decatur Button, an architect from Connecticut whose work is found throughout Philadelphia and Camden. His mid-19th century designs included the entrances for Colestown Cemetery in South Jersey and Odd Fellows’ Cemetery in Philadelphia, as well as the pre-Civil War Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg.

Elsewhere in Philadelphia, Button built the handsome brownstone Gaul-Forrest Mansion on North Broad Street that became the home of Freedom Theatre. In Camden, he was chosen to design the first city hall, and his hotels include the landmark Congress Hall in Cape May.

Button’s brownstone gatehouse at Mount Moriah originally included administrative offices and a tower that rose from what had been lodging for cemetery staff. The structure is situated near 62nd and Kingsessing streets, roads which didn’t exist when the cemetery was established. Visitors arrived by horsecar or omnibus along Woodland Avenue, then took a short walk to the cemetery entrance. Visitors in the next century could take the electric trolley from the city to the cemetery.

“Mount Moriah was one of many rural cemeteries that tried to make the model of Laurel Hill [Cemetery] more affordable,” Wunsch said.

In addition to cost, the better-known burial grounds like Laurel Hill and The Woodlands had social and racial barriers. “So African-Americans and Jews and benevolent associations began setting up their own cemeteries. Mount Moriah was never officially the terrain of any one of those groups. But it was colonized by them and served as a collector of church lots and association lots and fraternal organizations like the Masons. They made deep inroads there,” Wunsch said. “Mount Moriah is much more a middle- and working-class cemetery.”

‘A patchwork quilt’

When it comes to rescuing old burial grounds, “There’s a group of people who care about cemeteries, and then there’s the rest of the world,” said Paulette Rhone, who as board president of the Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery falls into the first category.

The Friends have 4,000 followers on Facebook; there are roughly 25 active members, in addition to the families who maintain their ancestral plots. They come to the grounds with their own tools, equipment and sweat equity to clear the invasive plants and debris and re-establish some order.

“We call it a patchwork quilt,” Rhone said of the landscape. “There’s woods, and then there’s a clearing, then there’s more woods…”

Mike Dwyer is a regular visitor on weekends, showing up in his four-wheel drive truck to clear the overgrowth, level the ground, and plant grass seed around his wife’s family plot. He knows Mount Moriah’s landscape well, including its most interesting memorials, like the Civil War sailor’s gravestone shaped like the armored Monitor and the Colonial flagpole honoring Betsy Ross.

The Friends, like Dwyer, are the “boots on the ground,” Rhone said. “They stay engaged on the land. While the other things are going on, the grass still grows.”

“The other things” are being coordinated by the Mount Moriah Preservation Corporation, which includes two appointees from Philadelphia, two from the borough of Yeadon, and three citizen appointees. Rhone is vice president of the corporation.

At the end of last year, the corporation secured a $22,000 grant from the Mayor’s Fund to be used toward the rescue of the gatehouse. After receiving an initial estimate of $90,000 to stabilize the structure, the corporation found a contractor who could do the work for $32,500. The Friends group led a fundraising effort to make up the shortfall. The firm Wiss, Janney, Elstner donated engineering services, and the permitting process is now moving through the Department of Licenses & Inspections, Rhone said.

The initial stabilization will involve setting up jersey barriers along the front of the gatehouse and shoring up the walls with supports. “It won’t be pretty, but it will keep it up,” Rhone said.

Future use

Graduate students in the Penn preservation program conducted a study in 2011 of the conditions of the gatehouse and recommended treatments for dealing with decades of neglect and decay. Temple University landscape design students have been working on components of a master plan for the cemetery grounds.

Rhone’s vision for Mount Moriah involves a focus on the two military sections, which include dozens of Civil War graves maintained by the Veterans Administration; the restoration of the hilltop Circle of St. John, which honors members of the Masonic order; and maintenance of the grounds established by the First Baptist Church of Philadelphia, which includes the remains of Revolutionary War officers.

“The thinking is, no one organization can lift this boat. It has to be a rising tide of different organizations who have a vested interest in Mount Moriah,” Rhone said. “Together, we can do it.”

While it hasn’t functioned as a cemetery since 2011, Rhone hopes that Mount Moriah can restore the historic gatehouse as a columbarium, a structure of vaults with recesses for urns containing cremated remains.

“Cremation seems to be the way the death care industry is going. If we can have a place for cremains, as we establish ourselves and become a respectable cemetery that people can trust with their loved ones, hopefully that will be able to generate enough income that we will become self-sustaining,” Rhone explained. Economic sustainability “is the ultimate goal.”

Wunsch said the Penn student report found that most of the gatehouse is “fixable.” He would like to see the gatehouse restored to most of its original design. “We have good documentation of what the whole building looks like. It’s unrealistic to reconstruct” each element, he said. But if is rebuilt as a columbarium, “there’s no going back.”

“If you stabilize a ruin, over time you could actually start putting it back together. Once the threat of collapse is gone, you could go at this thing slowly.”

The Preservation Corporation’s Abernathy, who is also the first deputy managing director in the Kenney Administration, said the gatehouse restoration is a prime concern, but “the larger issue is where does the cemetery fit in the neighborhood and in the city going forward.”

Challenges remain over the ownership structure of the cemetery and on finding the funds to develop a strategic plan. “Certain funders and philanthropists have an interest in assisting us in that mission,” Abernathy said. “I’m confident that we’ll be able to move forward in the next year on what the cemetery wants to be, and we’ll create a plan that does not rest on the backs of volunteers, as it does now.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.