Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation at 50

There’s a vacant cultural center — but it faces a lively parklet. There’s plenty of dim sum — yet it’s possible to enjoy craft cocktails at a not-so-hidden location that’s been called “one of the best bars in the world.” There’s the Year of the Monkey fireworks — and the promise of this year’s Night Market.

Philadelphia’s Chinatown is the same as it ever was, but it’s constantly reinventing itself. Much of the credit for that goes to the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC), established in 1966 and now one of the nation’s oldest ethnic CDCs.

“The organization was founded around advocacy efforts in the face of the encroachment of the Vine Street Expressway,” says Beth McConnell, policy director for the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations. “Over the years, though, its greatest accomplishment has proven to be the vibrancy of Chinatown itself. It’s a tourist attraction, a regional hub for Asian populations, an economic development engine for the city, and a safe and attractive neighborhood. The work that PCDC has done has created a real community there.”

Since that initial Expressway assault, the PCDC has periodically fought other battles, including against a ballpark and casino, and won. Along the way, it also built a rich legacy of market-rate and affordable housing development, programs to support immigrants and youths, and quality of life improvements like pedestrian lighting and street cleaning programs.

John Chin grew up above a family-owned restaurant across the street from the neighborhood firehouse and has seen the changes firsthand. He attended Holy Redeemer Church, the same edifice which stood in the way of the very same Expressway, and which the fledgling PCDC worked to spare. It’s not surprising then, that Chin would eventually join the organization, serving as its executive director for the past 16 years.

“I’m 50 and it’s 50,” he says with a laugh. “We’re both horses [in the Chinese Zodiac] — that means we run around a lot and are good at attracting friends.”

Chin affirms that the inevitable evolution of the neighborhood isn’t all bad. “The PCDC is about helping people see Chinatown in a very different light than the one they might be used to,” he says. “It’s a view of the neighborhood as a place with a lot of possibility and opportunity. Yes, we’ve been struggling with gentrification for many years — but what are we preserving? I think the answer lies in accepting the fact that my parents’ generation and today’s might have different ideas of and expectations from the place we call Chinatown.”

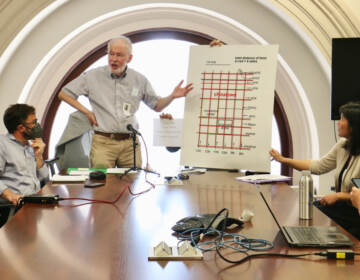

The majority of new businesses coming into the area have no previous connection with it, he points out. “But the Chinatown of today is bigger than ever, extending north to Spring Garden, and there are more businesses than we had a few decades ago.” A 2013 three-city study on gentrification and sustainability in Chinatowns found the population of Philadelphia’s Chinatown (Spring Garden to Filbert, 9th to 13th streets) to have grown 143 percent between 1990 and 2010.

“Our vision is that Chinatown becomes a part of the larger city — our planning perspective is not inward looking, but outward looking,” Chin continues. “We welcome opportunity and diversity. Yes, we have a huge need for affordable housing as the neighborhood improves and develops, but we absolutely believe in a mixed-income neighborhood. It’s the only way to succeed.”

Some critics have balked at that outlook; seeing in it capitulation to the development pressures that buffet the neighborhood from all sides. Last year, Chin offered a pointed response, mocking them as “vague sentinel calls . . . deploring displacement, cultural murder, and the private developer.” Let others boo hoo. The PCDC would go on doing the “business of community development,” he wrote.

“The CDC has been priced out of the [real estate] market,” retorts Domenic Vitiello, associate professor of city planning and urban studies at the University of Pennsylvania and author of the 2013 study on Philadelphia, Boston, and New York’s Chinatowns. “For the most part, it’s been a real struggle for them to stay in that game and they now offer a much more diversified set of services. That’s all good, but affordable housing was once very much part of their core reason for being.”

Since the ‘80s, PCDC has managed to squeeze 226 affordable housing units into the residential mix, including projects in partnership with other organizations. Last year, it opened 810 Arch Street, the Francis House of Peace, developed with Project HOME. According to Chin, some 1,000 families from around the region applied for its 94 affordable units. “Now, it’s probably the most diverse apartment building in the city,” he says. “We’ve got the formerly homeless, people from the LGBT community, youth aging out of foster care, seniors, you name it.”

Chinatown’s proximity to Center City may be responsible for its desirability to a crop of affluent urban dwellers — including, as Vitiello points out, native Chinese such as the college students he teaches at Penn and wealthy investors from the mainland looking to park their money — but it’s also a burden.

“Because Chinatown lies within the Center City census tract, it’s no longer eligible for community block grants,” McConnell says. “The federal government requires that money be spent in neighborhoods where more than 50 percent of residents are low-income.” Chinatown proper also suffers from a dearth of vacant parcels, aside from a few parking lots, she adds. “This idea of achieving a more complete vision of building affordable homes and welcoming new investment — there’s a lot of tension over why it isn’t happening but the access to actual developable land is clearly a problem.”

And, so, northward ho!

For almost two decades — starting with the 1997 opening of the award-winning Hing Wah Yuen, a housing development with a mix of market and affordable rate units — PCDC has been a driving force behind efforts to push Chinatown north of the Expressway. “Over the years, we’ve lost about 25% of our land,” Chin says. He doesn’t say it, but the meaning is clear: this is the way to take some of it back.

While most of the incursions of the past came from the east, west, and south — thanks to developments like the Gallery and the Pennsylvania Convention Center — generations of Chinese once lived as far north as Callowhill, where Holy Redeemer became a neighborhood icon. These northerly parcels eventually turned over to light manufacturers — fortune cookie factories and tofu-makers still operate here — but by the year 2000, the PCDC’s efforts to re-zone 44 acres for residential use were finally realized.

Seemingly ever since then, its vision has hinged on one large development at the northwest corner of 10th and Vine: Eastern Tower, a $77 million, 23-story mix of community center, ground floor retail, office space, and apartments. Chin says the latest projected groundbreaking is for this June.

For now, a new-ish pedestrian plaza on 10th Street over the Expressway does a serviceable job of bridging the gap between the old and the emerging Chinatown on either side of the gash. Soon, will come a new master plan and preservation efforts to bring new life to the vacant Chinese Cultural Center (the idea of a museum has been tossed around).

When asked what Chinatown will look like in ten years, Chin immediately answers, perhaps immodestly, a “mini Hong Kong.”

“This moment of businesses catering to a younger and more affluent crowd is attracting a lot of visitors and pedestrians. The product is modern and creative, but still very Chinese, and Asian. We still have a range of price points.

“This is expensive for me,” he continues, indicating the $11 Terakawa ramen bowl he’s just ordered. “I usually get lunch for $6. But this mix is important because the only way people can climb out of poverty is if they earn a living wage. You don’t have as great an opportunity for that at the place that sells lunch for $6.”

That the PCDC remains committed to helping Chinatown’s lower-income residents is evident in initiatives like the Family Support Service Program, which helps those in need take advantage of various social agency offerings. That it’s interested in being “modern and creative” is evident to just about any close observer.

For instance, the PCDC is getting attention nationally, McConnell says, by taking advantage of the EB-5, a special visa that eases the way for foreigners willing to invest in projects that stimulate jobs creation and economic development.

“John and his staff are real pioneers,” McConnell continues. “Other CDCs are looking to see how this works and what they can learn from PCDC’s experience. It’s exciting to see one of our own advance the field.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.