Takeaways from the 2016 State of Center City report

Center City District released their annual State of Center City report [PDF] Thursday, and while there are no major surprises about the trajectory of Philadelphia’s central business district—-up, up, and away!—-there are a few key takeaways and trends that point to where the city is headed.

Center City’s success is all about the deep service economy

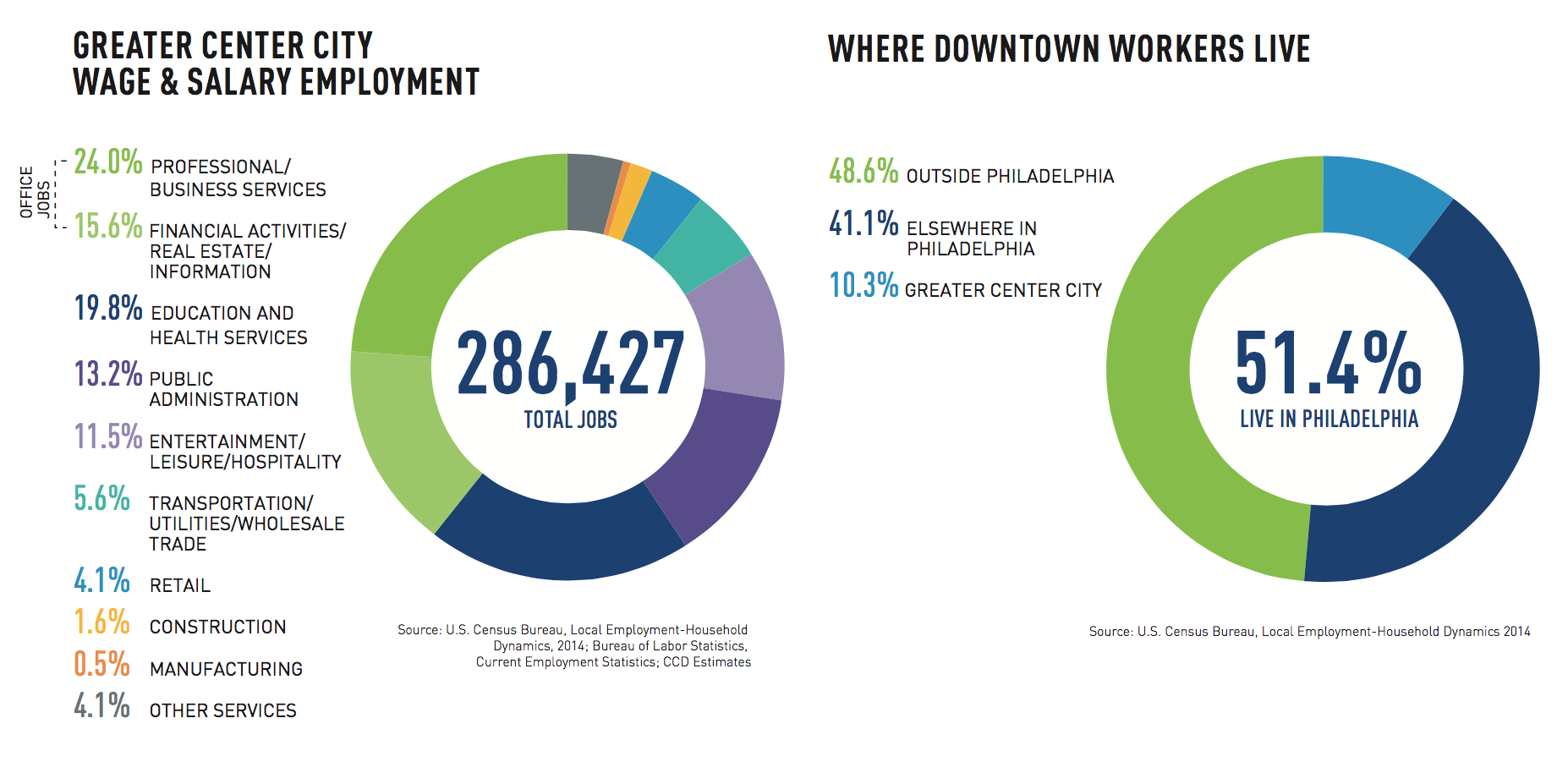

Images of factories, ports, and pipelines tend to capture the imaginations of elected officials when they discuss job growth in Philadelphia, but the reality is that almost all of the job growth occurring in the fastest-growing parts of the city is coming from the service economy, specifically the kinds of person-to-person services cities excel at providing.

As economist Joe Cortwright put it in the Storefront Index report we wrote about yesterday, “in effect, the city is an important labor-saving technology…[C]ities reduce the amount of time households need to spend searching for and traveling to different locations to select, acquire and consume many goods and services.”

The service economy feeds off of proximity, and Center City—-comprised of the office district but also Philadelphia’s densest mixed-use neighborhoods—-has this in spades. At a time when more and more of the retail market is moving online, it’s no coincidence that the types of businesses most interested in setting up shop in Center City (professional and business services, real estate, finance, hospitality, and more) are sectors that still require face-to-face interaction.

“Continue urbanizing” is probably the world’s least inspiring jobs program, certainly less exciting than natural gas pipelines and eminent domain adventures. But by all accounts it’s the process that seems to bear the most responsibility for attracting the kinds of jobs that Philadelphia has been producing, and it’s striking how little attention this gets as part of the official jobs conversation.

Center City growth is neighborhood economic development

Encouraging more Center City high-rises doesn’t sound like a neighborhood-centered economic development program, but it could be.

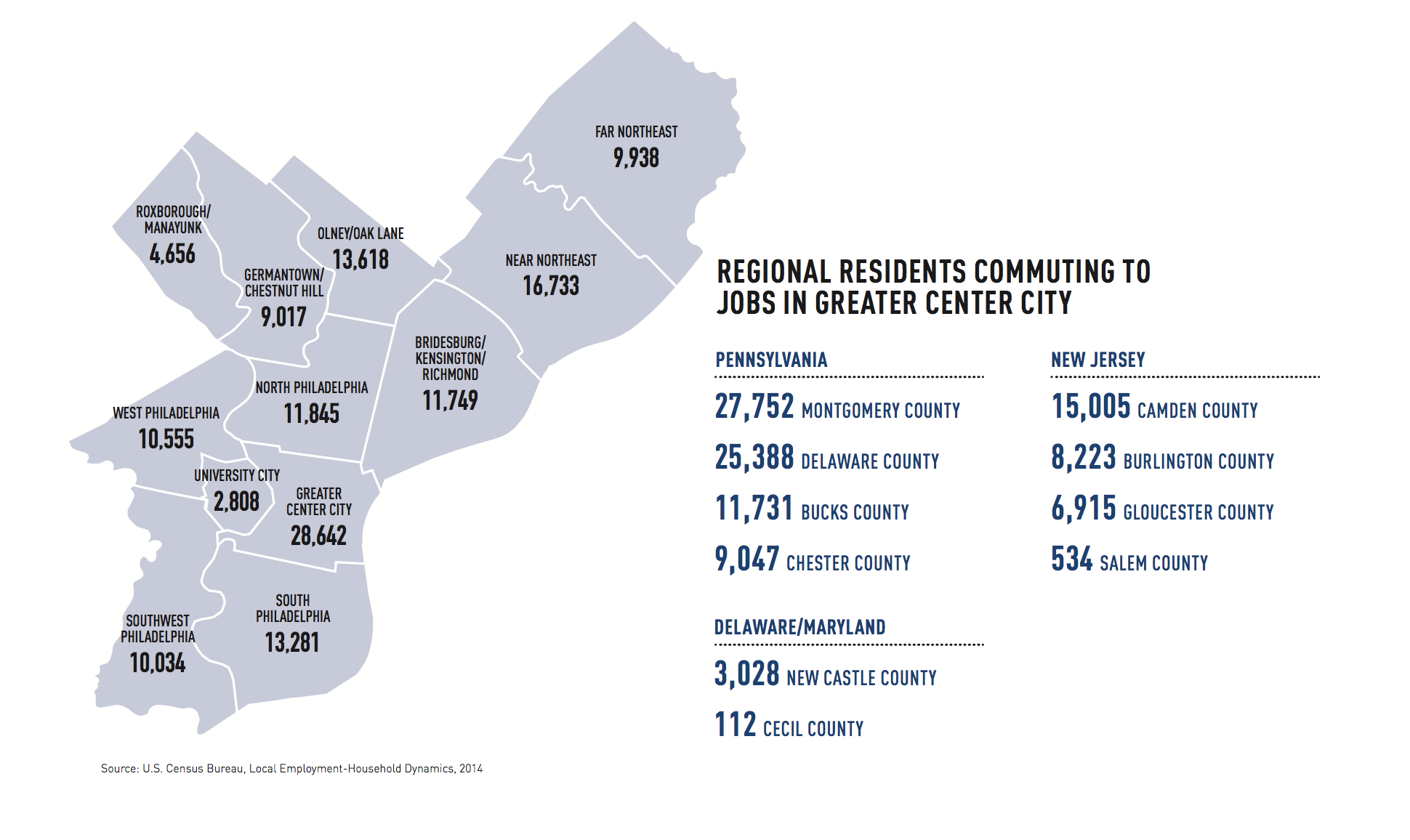

Around 41 percent of downtown workers are Philadelphia residents who live outside the greater Center City area. It’s true that “job sprawl” is a more prominent phenomenon in our region, as opposed to metros with one strong central job center. But within the city, Center City and University City are the two largest job centers and they support a diverse range of jobs for people all up and down the economic ladder.

As the report points out, high-rise offices “provide the most diverse employment opportunities: high-skilled positions requiring at least a college degree, technical, support and clerical jobs, as well as building engineers, security personnel and janitors. Every time tenants turn over, construction trades renovate space.”

Downtown workers also provide the customer base for retail, restaurants, and other consumer-focused retail, and Center City District (CCD) estimates they contribute over $221 million in retail demand each year.

People who work in the central business district, but reside outside of that area, also provide an important part of the customer base for the neighborhood commercial corridors where they live. Which is all to say that, while last year’s Mayoral contest featured a lot of rhetorical juxtaposition of Center City vs. neighborhoods, the idea of a zero-sum competition between different city regions is overblown since many neighborhood businesses and real estate markets are supported indirectly by the job centers in the urban core.

The good news: Steady Housing and Office Demand

The latest numbers paint a picture of Philadelphia’s central business district in ascendance, at least compared to its own recent performance. Among the highlights:

-

25 percent of residents who migrated to the city between 2010 and 2014 landed downtown, bolstering demand for central housing. The year 2015 saw 1,538 housing units completed in Greater Center City—-the third year in a row that more than 1,500 units came to market.

-

Research from the Philadelphia Fed found Philadelphia’s share of regional housing unit permits rose from 3.4 percent in 1989 to 34.2 percent in 2015, outpacing each of the collar counties in every year since 2010. (Despite much hype about a “Great Inversion,” in the Philly metro at least, 66 percent of the region’s housing construction is still happening outside the city.)

-

Developers constructed 4,124 apartments in Center City over the past three years, which exceeds the total number built in the previous ten. Across greater Center City, rentals account for 59 percent of total housing supply, and over the next few years, supply and demand are expected to remain roughly balanced.

-

Office occupancy rose from 86.7 percent in 2014 to 88.5 percent in 2015, surpassing the average occupancy of 85.2 percent in the suburban counties. The average asking rent of $27.44/sf is a slight increase from 2014, but is still much lower than average rents in Midtown Manhattan ($80.97), and about half the asking rents Boston ($55.60) and Washington, D.C. ($51.35).

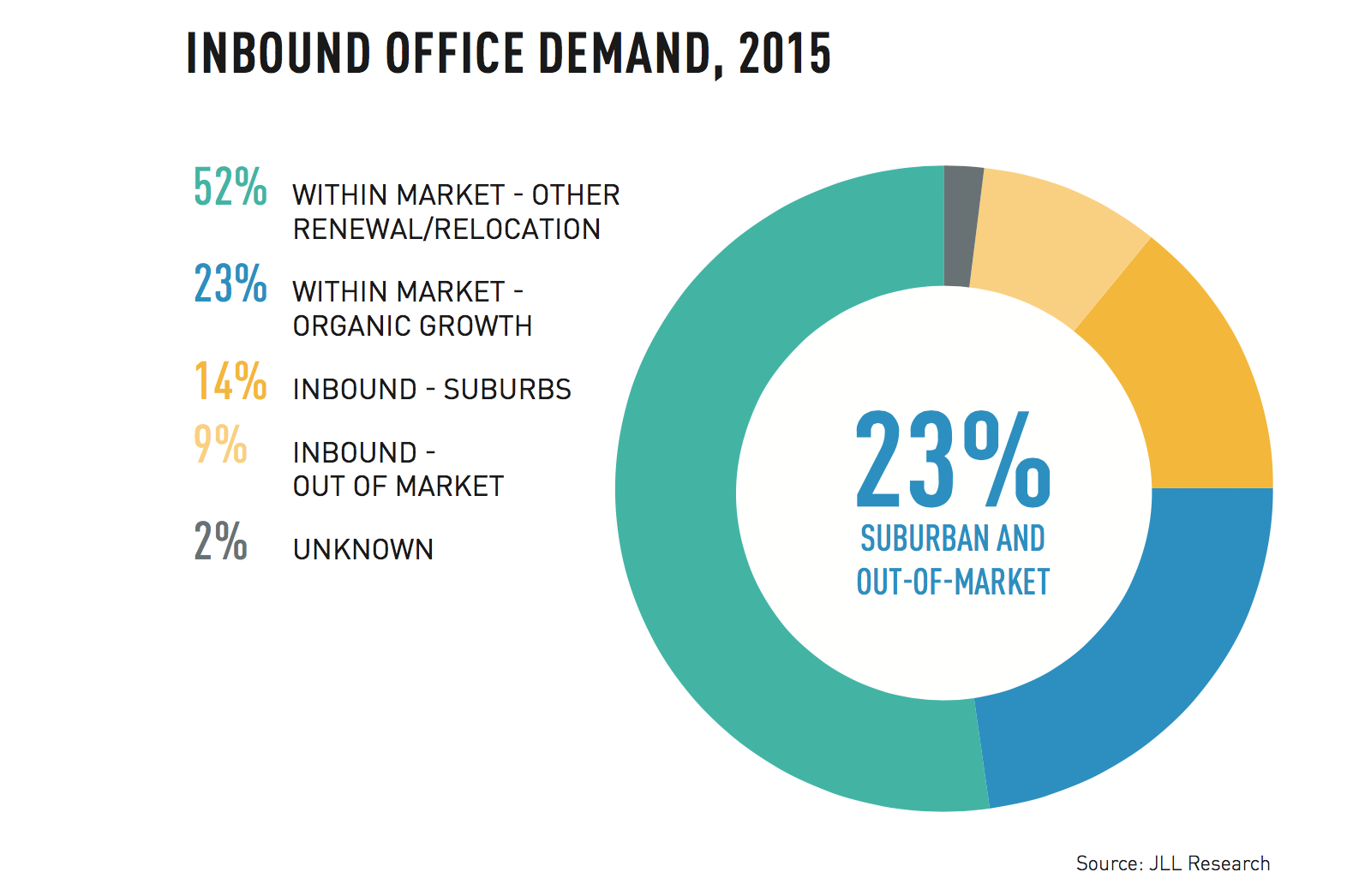

- The year 2015 saw more inbound office demand from the suburbs and other places than previous years, at 23 percent of the total. CCD sees a trend of outside companies using co-working spaces as incubators to test the market, before diving fully into a move downtown. 74 percent of the 4.6 million square feet of existing downtown office inventory that changed hands in 2015 was bought by out-of-town investors.

The bad news: Lagging growth compared to other big cities

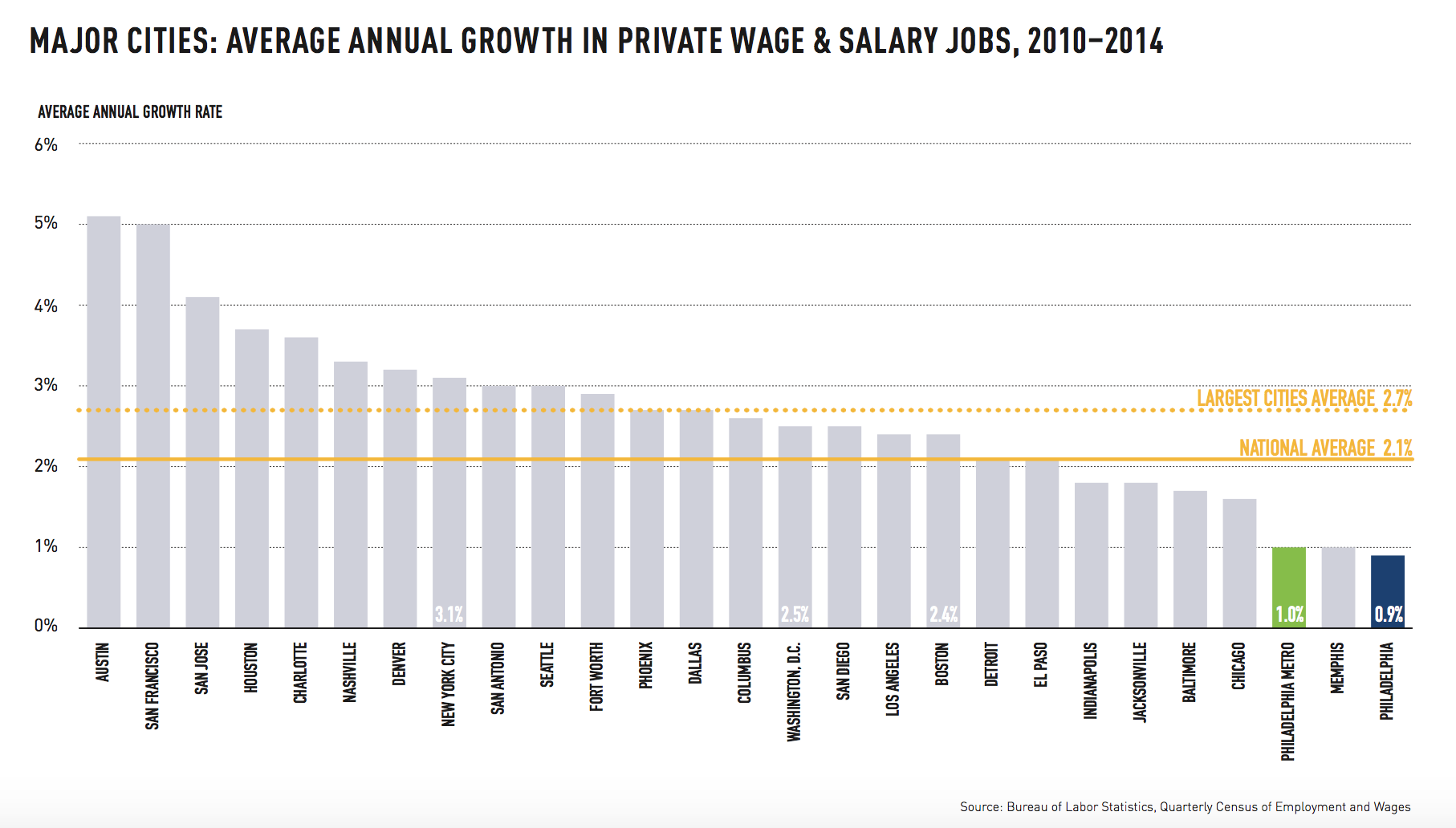

Relative to its own recent past performance, Philadelphia’s central business district is experiencing a Renaissance. But compared to many other large U.S. cities, our recovery still lags.

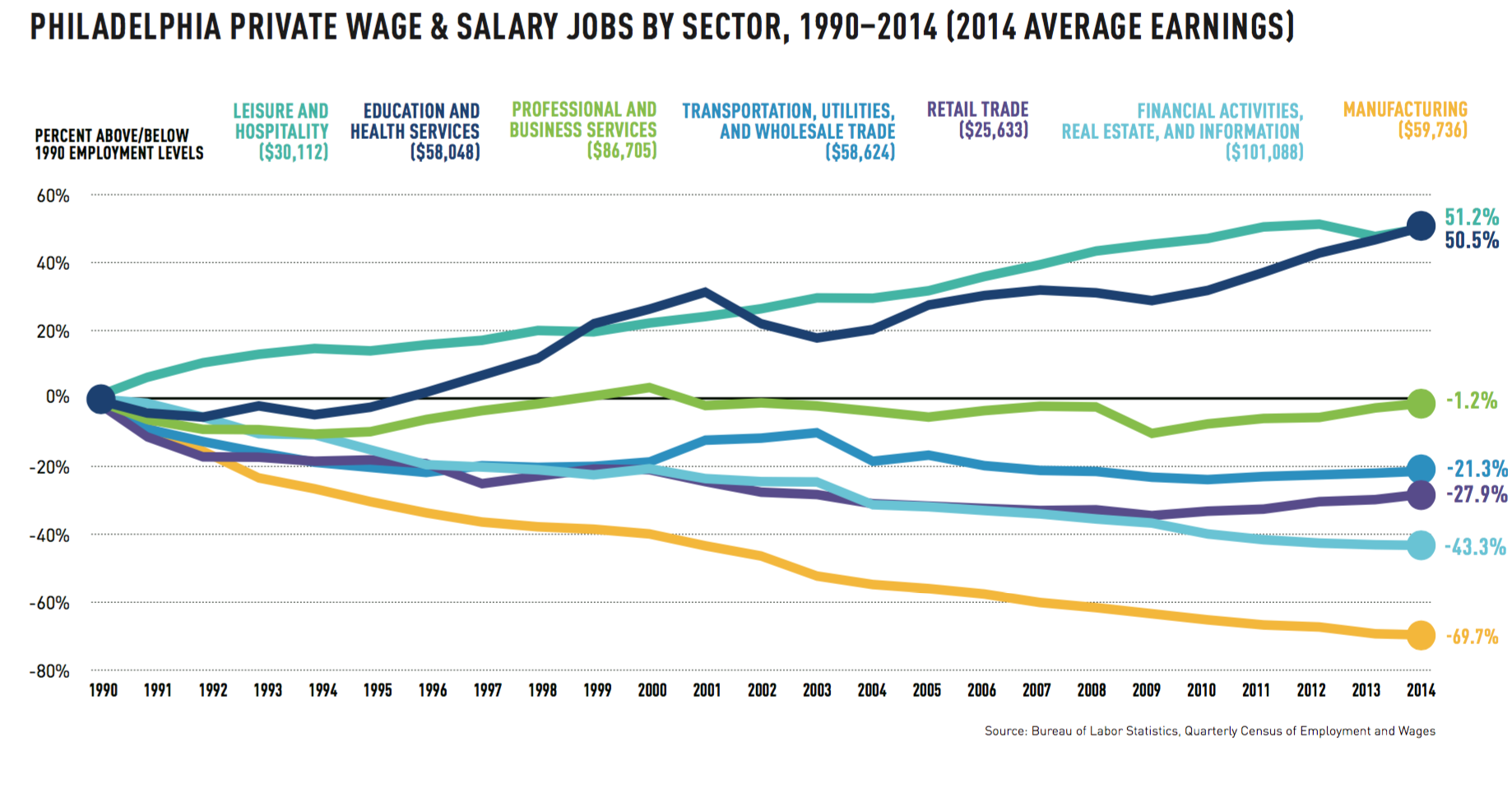

The city’s two largest sectors, education and health services, grew by 50.5 percent citywide since 1990; and leisure and hospitality increased by 51.2 percent in that timeframe. But the industries that drive demand for office space, like professional and business services, are down 1.2 percent, with finance, real estate and communications sectors shrinking 43.3 percent over the last 25 years.

There’s also little sign that firms are willing to pay a premium to locate within the city or the central business district. Center City District points to research from Newmark Grubb Knight Frank that found an average CBD premium of 25 percent for major urban markets in 2015. That premium is currently 112 percent in Boston and 75 percent in Washington, D.C, but in Philadelphia it’s only 4 percent. Philly has 28 percent fewer jobs today than in 1970.

Private-sector jobs in the 25 most populous cities have grown by about 2.7 percent annually since the Recession, but in Philadelphia they’ve grown by just 0.9 percent per year. Even other poor Rust Belt cities like Columbus, Detroit, and Indianapolis have outperformed Philadelphia’s job growth since 2010.

As Center City District publications are wont to do, the report calls out Philadelphia’s reliance on wage and business taxes to supply 63 percent of its municipal tax base as a significant drain on local business activity, which they say depresses local rents and weakens demand for goods and services.

The city’s wage tax is still four times the average found in the suburban counties, they note, and for local companies, business taxes add around a 20-30 percent premium to the cost of doing business. Meanwhile, local real estate taxes are about two-thirds of the regional average.

In a Center City Digest essay [PDF] accompanying the report, CEO Paul Levy makes the case that the persistence of sluggish job growth despite otherwise strong local economic fundamentals, and the backdrop of a national revaluation of large cities, is evidence of the need for tax reforms he has long championed.

Levy and Brandywine Realty Trust CEO Jerry Sweeney have championed a bill in Harrisburg to allow Philadelphia to trade wage and business tax reductions for higher commercial property taxes. The proposal enjoys support from Mayor Jim Kenney and Philadelphia’s state delegation, though City Council President Darrell Clarke and some Council members oppose tying the city’s hands in committing all the proceeds from higher commercial property taxes to wage and business tax cuts.

The change would require an amendment to the uniformity clause in the state Constitution, which has been interpreted as requiring flat taxes, so it faces fairly daunting odds, but Levy and his compatriots have assembled an impressive coalition for tax reform that has managed to move the issue further down the field than previous attempts have managed.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.