Local environmental group questions SEPTA proposal for natural gas plant in Nicetown

SEPTA enjoys a pretty good track record when it comes to bridges, maintaining over 350 that consistently deliver trains safely over rivers and highways across the region. Commuters sometimes grumble when the transportation authority cuts back service for repairs, but for the most part, everyone understands: This is necessary, we need bridges.

But bridge fuels? There, SEPTA finds itself facing a bit more than mere grumbling, as a group of environmental activists have launched a campaign in opposition to a natural gas cogeneration plant proposed near SEPTA’s Wayne Junction power substation, between the agency’s Roberts Yard and Midvale Depot in Nicetown.

SEPTA says the proposed $26.8 million, 8.6-megawatt combined heat and power (CHP) facility will save it money, improve regional rail’s reliability, and have a net positive impact on the environment because it will replace electricity from dirtier coal-fired plants.* Thanks to a public private partnership under Pennsylvania’s Guaranteed Energy Savings Act (GESA), SEPTA won’t even have to front the construction costs—the authority would sign a 20-year contract to pay an amount guaranteed to be cheaper than its current electricity bill. To SEPTA, it’s a no-brainer, assuming that an independent environmental study it commissioned shows that the plant wouldn’t significantly exacerbate local air quality.

But some environmental groups, led by 350 Philadelphia, say there is simply no justification for burning any additional fossil fuels, especially not in a lower-income neighborhood already suffering from high pollution levels. Climate change, 350 Philadelphia argues, must be fought with the fierce urgency of now; an addiction to gradualism, that tranquilizing drug, threatens to kill us all. If that weren’t enough, SEPTA’s promised savings might vanish if—as they hope—renewable energy becomes a cheaper electricity alternative.

So 350 Philadelphia organized a meeting last Thursday to discuss concerns about the potential for spiking asthma rates and fiscal irresponsibility before a small crowd of fellow travelers and community members. Even though SEPTA announced the project in a press release back in October, after it selected Noresco LLC to design the $26.8 million facility, neighbors said they weren’t aware of the proposed plant before the meeting.

“This is the first I’ve heard of it,” said Vernon Reynolds Sr., a Democratic committeeman in the 13th ward. “The word wasn’t out. SEPTA didn’t reach out [to] people at all.”

The fears, and the community meeting itself, are premature, said Fran Kelly, SEPTA’s assistant general manager of public and government affairs. Nothing has been decided for certain yet; authorizing the facility’s design is different from authorizing its construction.

“I didn’t want to come to a community and say we might be doing this,” said Kelly. SEPTA is still negotiating contract terms with Noresco, which is itself wrapping up an investment grade audit on the proposal and an emissions study required to secure permits. The audit will be used to shop interest rates from banks to finance Noresco’s construction of the CHP facility. SEPTA’s also waiting for a separate, independent environmental impact study by Mondre Energy Consulting, which, according to Kelly, the authority commissioned on its “own volition to make sure we had the best available information.” It’s expected to be released sometime next month. The project won’t be ready for the SEPTA Board’s final authorization until late summer or early fall, he said.

SEPTA’s energy futures bet

Setting aside the philosophical differences over burning fossil fuels, a pragmatic question remains: Does it make sense for SEPTA to lock itself into a 20-year contract to purchase energy from a natural gas plant?

Under GESA, SEPTA seems to have a pretty sweet deal. A bank, selected via a bidding process, would pay for the $26.8 million CHP facility’s construction. SEPTA would then pay off those loans using the savings from switching to the new facility over what is currently pays for heating and electricity. The facility would largely replace the PECO “base load” at the Wayne Junction substation, which powers all SEPTA’s regional rail trains north of the Temple University stop. Right now, SEPTA pays around $8.5 million a year for 104-megawatt hours per year at the Wayne Junction substation. The facility would be able to power trains at a weekend level; the remainder required for more energy-thirsty weekday service would still come from PECO.

Noresco, the firm designing and building the CHP facility, would guarantee the savings compared to that $8.5 million figure, based on the efficiency gains from a combined heat and electricity plant — the facility would replace old boilers at SEPTA’s nearby rail yards and the massive and drafty Midvale Bus Depot. SEPTA says there are other energy savings it’s not including in these calculations, including retrofits to the nearby facilities to reduce electricity consumption. By making the switch, SEPTA estimates a 15 percent overall reduction in its greenhouse gas footprint. And all of the savings would be guaranteed by Noresco, seemingly making this upgrade free both in terms of capital costs and risk.

But there’s one risk that SEPTA may be exposed to: The risk that natural gas prices will become more expensive than electricity prices sometime during the locked-in 20 year contract term. For that to happen, some sort of major technological or political change would need to occur to make renewable energy (or nuclear power) more affordable than burning fossil fuels.

Currently, the price of natural gas affects the cost of electricity. When the price of one cubic foot of natural gas goes up, the price of one kilowatt of electricity tends to rise with it. Natural gas is an input in making electricity, so it’s fundamentally cheaper, the way milk is cheaper than cheese, or alfalfa is cheaper than beef. SEPTA argues that electricity’s price sensitivity to natural gas will continue for the foreseeable future; 350 Philadelphia believes renewables will replace fossil fuels sooner rather than later.

Coal and natural gas each produce around 33 percent of today’s electricity in the U.S., with coal’s market share declining as more utilities switch to cleaner natural gas. Solar and wind power make up just 5.3 percent.

Once the technology for solar and wind advances sufficiently, it could overturn the entire energy market. Unlike gas, coal or even nuclear power, the fuel for renewable technology is free. The variable costs of these renewable energy sources are practically non-existent, at least compared to the price of buying another ton of coal or barrel of oil. When operating costs shrink to nearly zero, it suddenly makes a lot more sense to invest heavily in building expensive new capital: In other words, to build a ton of new wind turbines and solar panels. The market shift could be swift and dramatic.

How likely is it that renewables overtake natural gas as the dominant energy source in Southeastern Pennsylvania over the next 20 years? That’s like asking who’ll win the Super Bowl in 2025: Someone who could answer that correctly and confidently could make some big bets and make a lot of money. Suffice it to say that renewable energy remains the smallest electricity source in the U.S. today, but it’s also the fastest growing. In the last 15 years, it’s share of the overall electricity production market has grown 321 percent according to U.S. Energy Information Administration statistics. If that trend continues, then renewable energy might overtake gas in about 20 years.

And if that happens within the next 20 years, then SEPTA will be stuck with their natural gas plant, forced to buy energy from it instead of the cleaner, cheaper energy available on the grid. SEPTA would be forced to pay to pollute.

The risk of SEPTA losing money isn’t why 350 Philadelphia is against the new CHP facility: They stand in philosophical opposition to burning any fossil fuels. But money is another reason why they say SEPTA should step up its efforts to invest in clean, renewable energy like wind and solar.

So why not build solar panels on the site, instead of the gas plant?

“Eighty-three acres” is the amount of space needed to generate as much power through solar, says Erik Johanson, SEPTA’s innovation director. The site of the proposed gas plant: just shy of one acre.

Power, pollution, public outreach

How dirty will this plant be? SEPTA has estimated that, in terms of burning gas, this will be similar to doubling the size of the Midvale Bus Depot, home to 300 SEPTA buses: it’s the equivalent of running 351 diesel buses, or 506 hybrid buses. (SEPTA has been slowly replacing their entire fleet with hybrids, and recently signed off on buying 525 more.)

The pollution that the CHP facility releases won’t be noticeable to the naked eye or nose: This 8.6-megawatt plant will have a considerably lower impact on air quality compared to Veolia’s 163-megawatt facility in Gray’s Ferry, for example.*

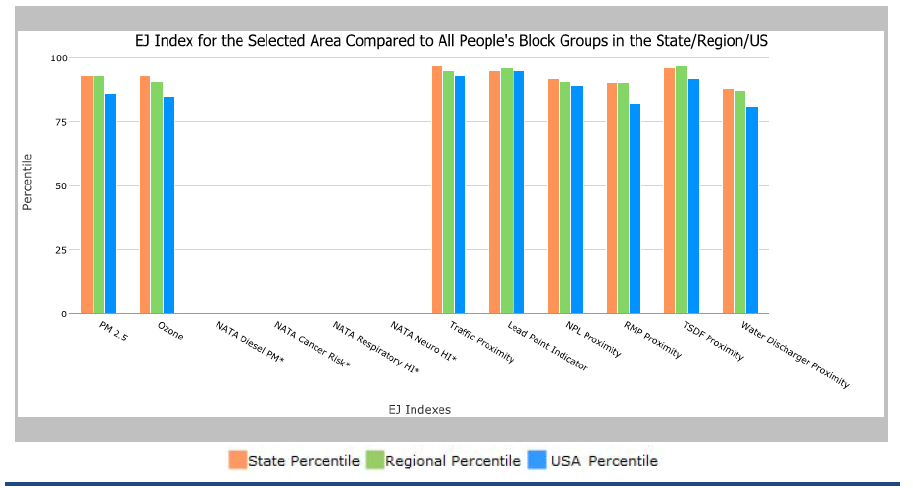

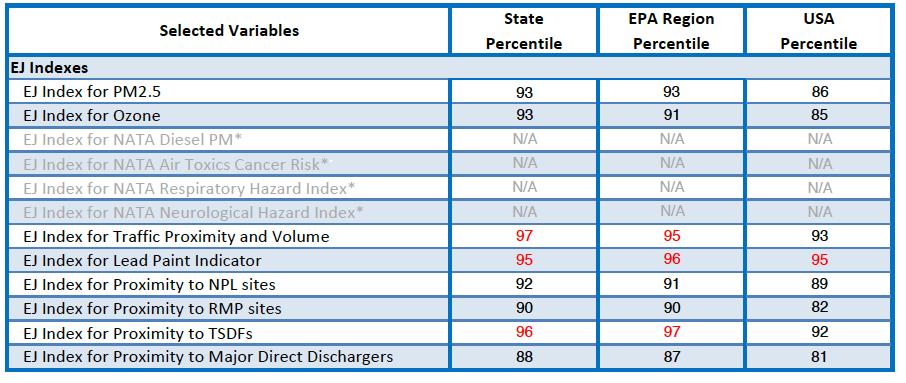

Still, this is already a neighborhood with elevated pollution levels.

SEPTA has also sold the plant as a reliability measure: Now these trains won’t be fully dependent on PECO’s grid, making a system shutdown from a power outage less likely. SEPTA says there have been “a few instances” in the last decade where they’ve lost all power at the Wayne Junction substation, even though it’s fed by two separate PECO lines.

PECO spokesman Ben Armstrong said that redundancy means those issues probably weren’t his company’s fault. “Any outages or system issues would more than likely be related to SEPTA’s equipment as opposed to PECO’s equipment,” said Armstrong.

In any result, this would provide triple redundancy. And, according SEPTA’s Chief Engineer, Dave Montvydas, even the slightest interruption can throw off the schedule for hours. “While PECO may come back in a few minutes, it takes us a full hour to get back to normal as far as power feed is concerned, and five to six hours to get our scheduled train traffic back to normal.”

SEPTA is using federal resiliency funding passed in the wake of Superstorm Sandy to also upgrade its signal systems along the regional rail lines powered through the Wayne Junction substation, which will allow the trains to run no matter what happens to PECO.

If SEPTA moves ahead with the plant, it’s unlikely that just a few scattered environmental groups will be able to stop them, which is why 350 Philadelphia is trying to find community support for their cause.

It’s a community that knows how to muster ranks, having formed a garrison to successfully ward off a bet-making barbarian before: In 2005, a coalition of neighborhood associations united in opposition to “TrumpStreet Casino,” a gambling hall proposed for the old Budd Company plant site, which would have been redolent in glitz and replete with a Mummer’s themed buffet, Boyz II Men branded bar and, of course, a Chickie and Pete’s.

It’s also is a community still raw from a recent proposal from the School District of Philadelphia to convert nearby Edward T. Steel Elementary school into a charter; the community fought that sudden-seeming proposal, hard, and remains sensitive to the perception of community outsiders swooping in with proposals for their neighborhood.

At Thursday’s meeting, Nikki Bagely, who has a son at Edward T. Steel, spoke, revealing the real risk SEPTA faces with this plant.

“I have issue with community not being as involved, to at least give me the option of knowing what’s going on,” said Bagely. “It’s just the arrogance of SEPTA not even coming out to talk to the residents, to let them know what’s going on, [for them to let SEPTA] know that you are surrounded by three public schools.”

“I’m just so frustrated sitting here and it’s just like, numbers written in a plan, and it has nothing to do with… this community.”

*CORRECTION: These sentences originally stated that the proposed facility would be a 67-megawatt plant. It is only 8.6 megawatts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.