Schoolyard redesign at Chester Arthur to support inquiry-driven learning

As the students of Chester Arthur School started the new school year, they noticed orange safety barriers traversing their schoolyard and snaking around the parking lot. The schoolyard is under construction as part of a renovation project that will transform the traditional schoolyard space into a multi-faceted outdoor learning environment—an extension of the indoor classrooms.

“We had to figure out how to create a public space that marries an educational vision with broader public engagement components,” said Ivy Olesh, president of Friends of Chester Arthur.

“Swings weren’t gonna cut it,” Mike Burlando said, explaining that innovation would be front and center in the schoolyard overhaul. Both Olesh and Burlando are board members of the Friends of Chester Arthur (FoCA), which has been raising funds for this project for four years. Major support came through a $1.1 million grant from the William Penn Foundation, $230,000 from the Water Department to manage stormwater, and $110,000 from the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority.

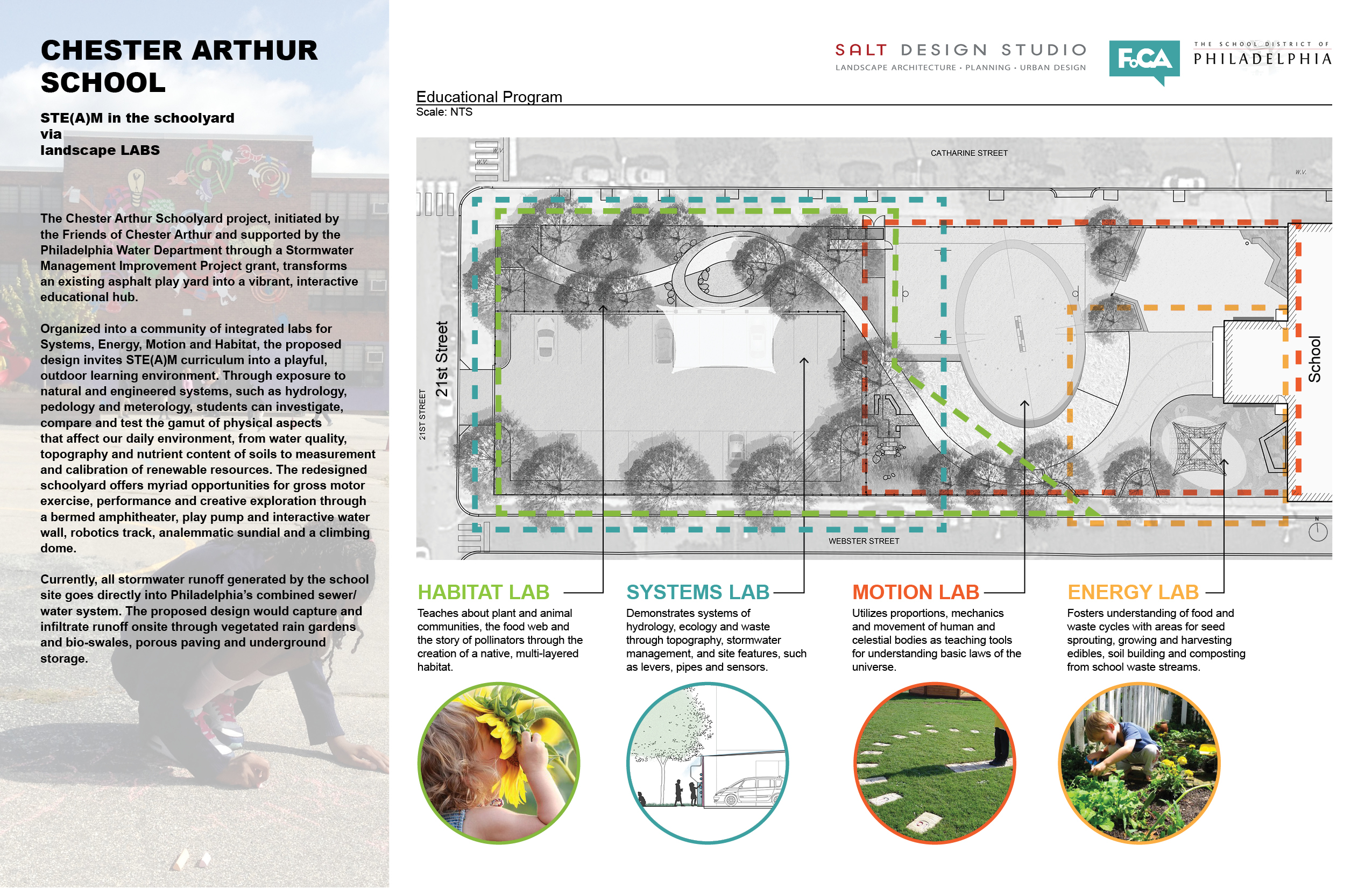

Whereas traditional playgrounds solely focus on exercise, SALT Design Studio has prioritized design elements through which students and teachers can explore STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) concepts. According to Sara Pevaroff Schuh, principal at SALT, the new schoolyard design would provide hands-on opportunities for students to learn and teachers to create lessons about a host of topics—from physics and ecology to geology and topography.

“The landscape can be a teaching tool for kids,” Schuh said. Each element, material, and area in the design can be approached in different ways, but all center on engaging the students in inquiry-driven learning—a focus of Arthur’s curriculum, which allows students to practice active investigation, rather than being taught straight facts.

“We had an interesting conversation [with the kids] about what made learning fun as opposed to asking, how do you want to play,” Schuh said. “What would make the learning part the thing that was so exciting, something that’s not so differentiated from play?”

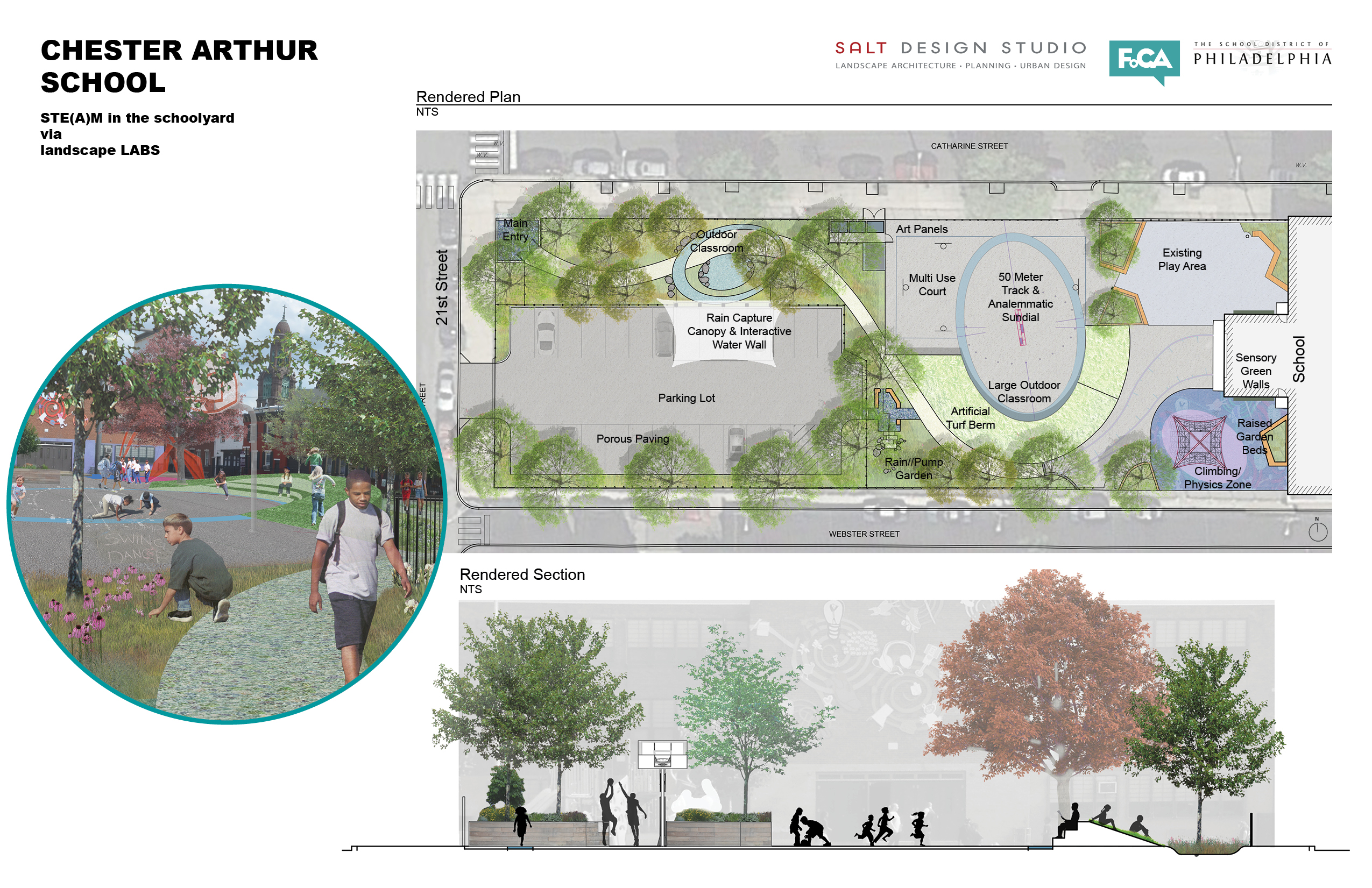

Schuh’s team created four different schoolyard “labs” based on program needs and input from teachers, students, and the surrounding community: a Habitat Lab, a Systems Lab, a Motion Lab, and Energy Lab. Each lab overlaps the others and includes freeform design elements to spark curiosity and ideas. There’s a 50 meter track and a custom-made climbing structure from which objects, like pendulums, can be hung; raised planters and plenty of trees; a sundial where kids can use their own bodies to understand how the sun moves across the site; and part of the parking lot will have porous paving that can collect an inch and a half of rainwater. An artificial turf berm adds height to the space, and it acts as an informal gathering setting, along with the more formal outdoor classroom complete with boulders of at least half a dozen types, but quarried from the same site.

Mike Franklin, a science and math teacher at the school as well as the leader of the civil engineering club, is especially excited for the rain canopy and interactive rain wall that will be installed over a portion of the parking lot. It will be a steel structure that collects rain with a pegboard wall on which kids can pipe water down and power LED lights using attachments. “We can focus on the power and potential of green energy and let kids learn about infrastructure and greywater collection systems,” Franklin said. “We can also learn about history, like water towers and why you don’t see them anymore.”

The original playscape and basketball court needed to stay in the design, and access from Catharine and Webster Streets had to be uninterrupted. Although the parking lot also needed to remain in order to allow teachers continued access to reliable parking, the design reorients it in order to maximize useful space for the students. Olesh envisions the parking lot as used for things other than parking, such as flea markets and a space for kids to learn to ride bikes.

At its heart, this project is also a placemaking initiative. Part of the process is teaching young learners how to be in the space, since at first they might not know how to approach a familiar schoolyard taking on such a different form. “Lots of students aren’t used to seeing plants in their schoolyard,” Schuh said. “[They might think,] ‘Are we supposed to run over them? Sniff them? Look for a bee or a butterfly?’”

Arthur teachers will help guide the students in this endeavor using curricula developed by the Center for Excellence in STEM Education at The College of New Jersey’s School of Engineering. Beyond that, FoCA hopes that the schoolyard, once completed in November, will be able to stay open all the time as a new amenity that welcomes the whole neighborhood.

Ground broke on June 15, and already, there’s been visible progress, particularly with the development of the outdoor classroom zone. The construction process itself is an opportunity to involve the students and for learning. They can discuss what they see happening and why, and construction workers can stop during recess to explain to the kids what’s going on and what different machines do.

Though schoolyards across Philadelphia are being reimagined and turned into greener learning environments, Chester Arthur’s is the first redesign to incorporate STEM initiatives into the design, but, as Schuh and members of FoCA hope, not the last.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.