Proposal to transform base of Ben Franklin Bridge trips at the start

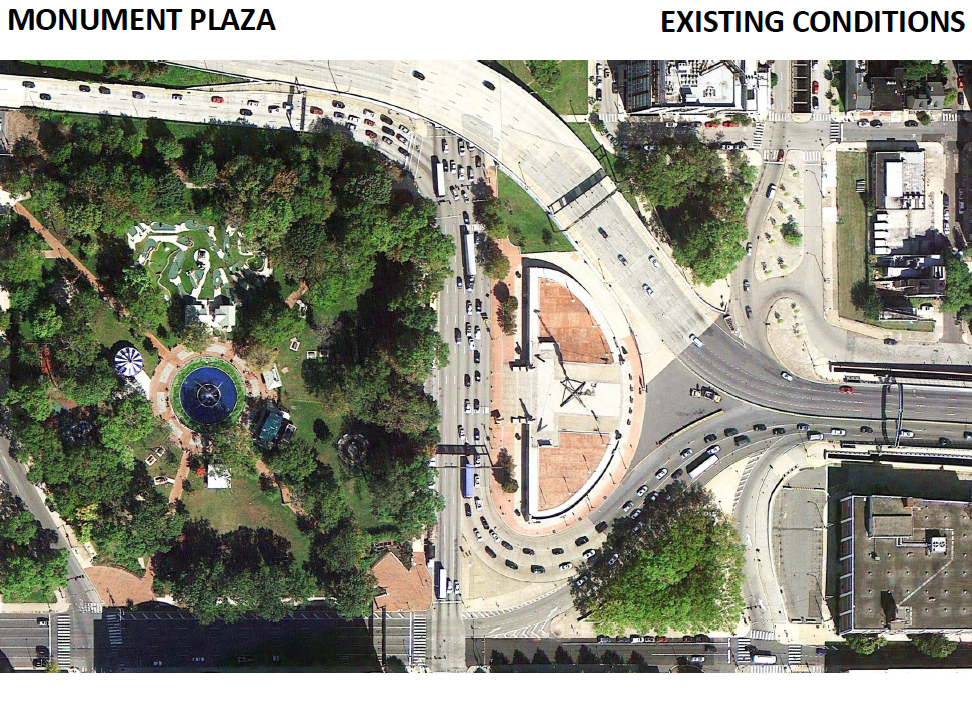

A few years ago, planners from the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS) approached the Delaware River Port Authority (DRPA) with an idea: Monument Plaza, the barren concrete pedestal for Isamu Noguchi’s sometimes loved, sometimes hated, and almost always overlooked Bolt of Lightning … A Memorial to Benjamin Franklin at the base of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, could use a makeover.

On that everyone seemed to agree: DRPA, the plaza’s owner; PHS, obviously; and PennDOT, which controls the roads leading to the bridge, not to mention the City of Philadelphia and a handful of nearby neighborhood groups. PHS was interested in sprucing up the sculpture site as an outgrowth of its Civic Landscapes Initiative, which targets a number of the gateways into the city for beautification. A pretty park would be more welcoming entry to Philadelphia than the lonely traffic island there today.

Safety first, though, added the DRPA. If PHS made the plaza more beautiful, green, and inviting, as it has with a number of other formerly underwhelming parts of Philadelphia, people will naturally want to go there, even though it’s surrounded by dangerous rivers of traffic, six lanes deep in some parts.

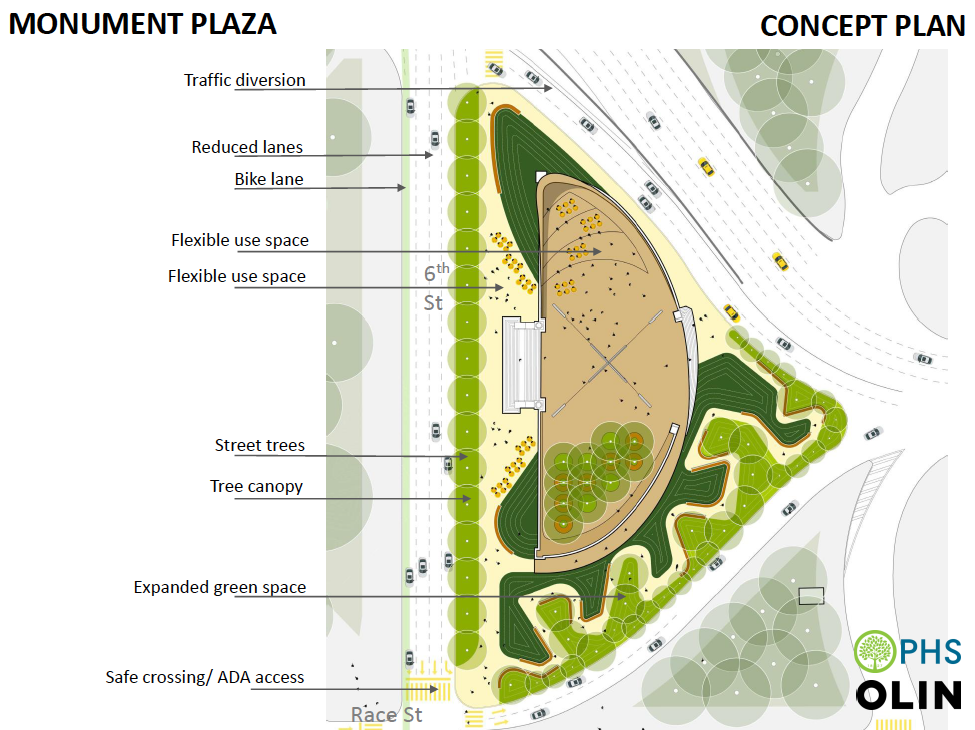

Of course, safety is paramount, said PHS, which then set about drawing up a preliminary concept that called for adding a small on ramp north of the plaza (between it and the bridge’s off-ramp), a move that would enable removal of two of the bridge’s three on-ramps, saving the infrequently-used entrance from Race Street near 5th Street. The changes would allow 6th Street to narrow down to four lanes (from six) and for PHS to plant a lovely little park.

That’s where things seem to have gone astray. PHS thought it had DRPA’s endorsement to put together a more robust conceptual design document—enough to market the plan to potential funders, like philanthropic foundations, on the merits of the project—based on the 2015 preliminary overview that called for new traffic patterns. PHS hired OLIN to whip up a bold landscape design, and engineering firm WSP Parsons Brinckerhoff to demonstrate that the on-ramp changes could theoretically work. If all the associated agencies continued to support the project, PHS could then go about raising funds for more in-depth engineering studies—how to actually build the new ramp—and then construction.

But the DRPA says it expected something much less ambitious. “When they talked to us, [the project] was simply beautifying the area where the monument was,” said John Hanson, DRPA’s chief executive officer. “What came back was a major change in the roadway and change to the bridge…that came as quite a surprise.”

“We’re not receptive to it where PHS is right now,” Hanson added.

Hanson raised a series of objections to the conceptual designs, as they were presented to the DRPA a few weeks ago. Monument Plaza sits atop PATCO’s underground tunnels, so DRPA needs assurances that any construction wouldn’t disrupt the trains. The curve off the Ben Franklin Bridge is fairly sharp, sometimes leading to tipped trucks, so Hanson worried about any changes that could make it sharper, or give less leeway to those tipped trucks. Part of the bridge decking in question is where the DRPA parks the “zipper truck” that shifts the bridge’s median to accommodate rush hour traffic. And then there’s question of whether any of this would damage the structural integrity of the bridge itself.

“Are these objections insurmountable? They are not,” said Hanson. But until those are “satisfactorily addressed” the bridge authority would withhold its support. “We see a lot of challenges and problems to address, but they aren’t ours to address.”

This is where the way forward gets tricky for PHS. Before it could solicit private foundations or apply for grants to cover the cost of an engineering study that could address DRPA’s concerns, the plan needs the DRPA’s enthusiastic support. Indeed, for the grants, it would have to be the DRPA that actually signed off on the applications, even if PHS did all the writing.

But, at this stage, DRPA refuses to offer its support. “Before they get a commitment from us, they need a commitment from PennDOT,” said Hanson.

In a statement, a PennDOT spokesman said “We have been involved in the meetings and continue to offer our feedback and support, and look forward to working with all partners on this project as they move forward.”

For its part, PHS was surprised by DRPA’s surprise, said Tammy Leigh Dement, parks project manager at the nonprofit who is leading the Civic Landscapes initiative.

Dement said that, at this stage, she was only seeking the DRPA’s approval to figure out the engineering challenges Hanson listed to PlanPhilly, not a definitive commitment or final backing. “We ask permission first,” said Dement. “We don’t go ‘Hey, DRPA, we have this idea…. We ask them to come in and work on it with us. That conversation hasn’t been had yet.”

But coming in and presenting definitive plans seems precisely what DRPA is used to seeing. “The appropriate protocol would be for PennDOT to come to us and say they want to build this road,” said Hanson, adding that they’d expect the state highway agency to come prepared with a finished plan, down to biddable construction documents. From there, the two agencies would hash things out, each confident in the engineering know-how of the other.

PHS doesn’t have that kind of relationship with the DRPA – the two haven’t worked together before. PHS usually partners with the City of Philadelphia and other nonprofits on their civic landscaping improvements, forming broad partnerships early on that take a collaborative approach to public projects. It’s a fundamentally different way of doing things, making it entirely possible that when each last agreed to take “the next step,” both PHS and DRPA envisioned entirely different things.

As a result, Hanson complained that “they haven’t given us a concrete proposal,” “it’s all fuzzy,” and “there’s no substance to what they’ve presented us.” Meanwhile Dement said she thought that would be “presumptuous” of PHS.

The basic idea of overhauling Monument Plaza and the surrounding onramps still enjoys support from neighboring community groups, though. Old City District included the concept in its Vision 2026 framework plan. “One of our goals is to make it easier for people to come to Old City [without driving],” said Old City District Executive Director Job Itzkowitz. “This is a way to make it easier and more comfortable to get down Race Street on foot. So without seeing final plans, we’re supportive in concept.”

His counterpart to the north was more effusive. “I think it’s great and I think it’s long overdue,” said Matt Ruben, chair of the Northern Liberties Neighborhood Association.* Ruben criticized DRPA for rebuffing Dement. “I’m not surprised that’s the reception she got,” he said. “I think any reasonable person or agency could have alternative ideas, or objections to certain provisions, challenges to deal with. But I think PHS is trying to start a conversation that’s well overdue to be had.”

“If [DRPA wants] to be good neighbors and behave according to their mandate, they should at least make a good faith effort to engage with an idea to make the area better.”

For now, though, it’s back to the drawing board. Dement said she will pare back the project’s scope and look to gain PennDOT’s prerequisite approval. Hanson said he was willing to continue discussing the project. Dement said she was optimistic PHS and DRPA could figure things out. “The way we approach things and DRPA approach things are very different…. I think we can get there.”

*Matt Ruben sits on PlanPhilly’s Advisory Board.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.