Researchers and residents explore ways Eastwick floods and ideas for mitigation

Eastwick is literally in a vulnerable position, environmentally speaking. The neighborhood is located in part of Southwest Philadelphia with the lowest elevation in the city; in fact, it was historically a vast marshland. And it is almost completely surrounded by water: The Cobbs and Darby creeks to the west, wetlands to the south, and the Schuylkill River and Mingo Creek to the east. Take this watery landscape and cross it with climate predictions for the next century, and it becomes clear that serious flood risk is very real.

The Consortium for Climate Research in the Urban Northeast (CCRUN) – a group of researchers from Columbia University, Drexel University, Hunter College of the University of New York, the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, and Steven Institute of Technology – is studying the effect of climate change in Philadelphia and other cities. According to CCRUN’s research, precipitation is likely to increase in Philadelphia, higher sea levels are extremely likely (which means tidal river flooding), and temperatures are extremely likely to increase, which means higher chances for extreme storms.

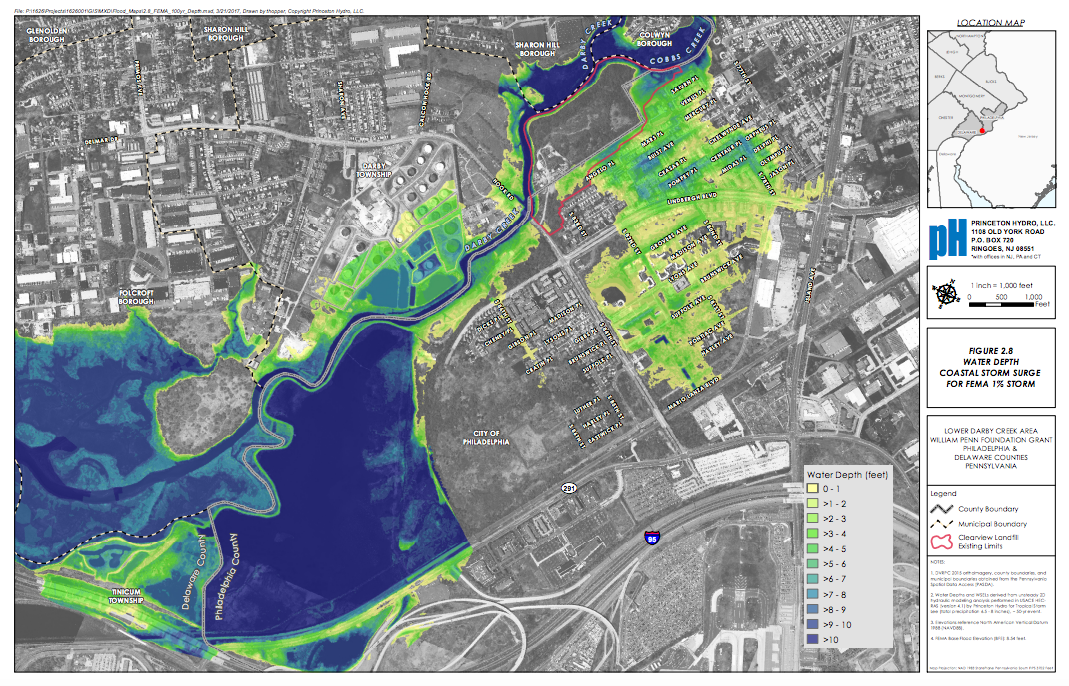

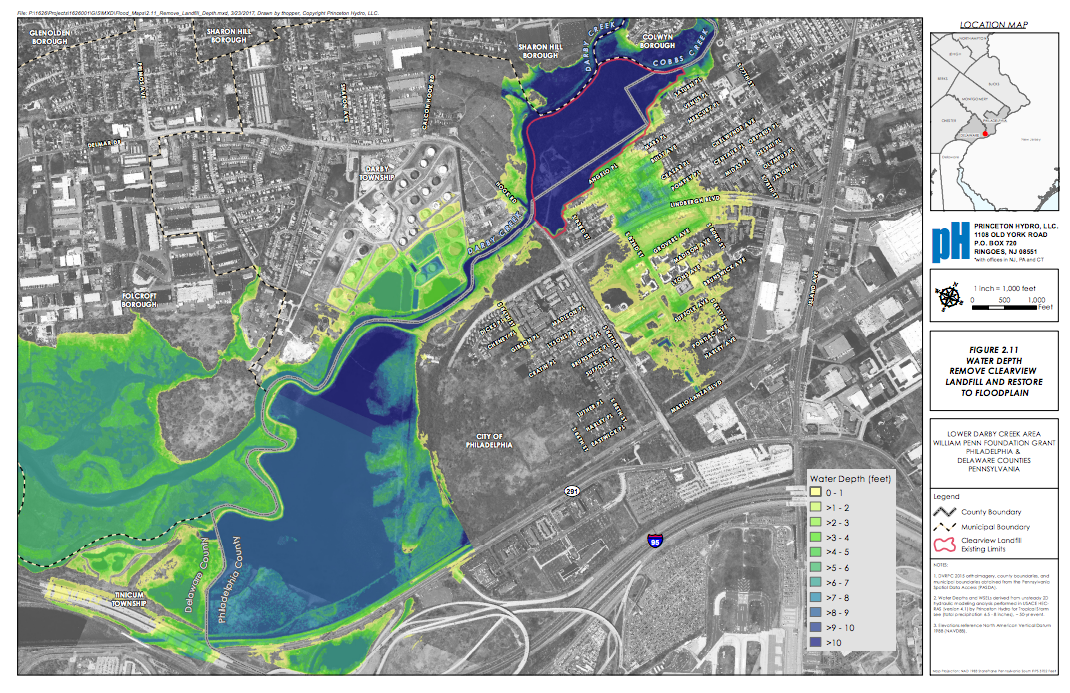

Storms already flood Eastwick. According to the Lower Darby Creek Area Research Team (a group of scientists and design professionals from the University of Pennsylvania, Keystone Conservation Trust, and Princeton Hydro also working on Eastwick), Cobbs Creek typically overflows at 78th Street. Normally the flow rate of the creek is low, but when a storm happens, runoff rushes into the creek making it rise quickly. Because the creek runs through a heavily urbanized landscape, it is more likely to experience flash floods. At the confluence of the Darby and Cobbs creeks, the flow is constricted by the former Clearview Landfill, which is part of the Lower Darby Creek Superfund site. The built-up landfill and the pinch point where the creeks merge can backflow into the Darby and Cobbs, which can flood lower ground around 78th Street, according to a Princeton Hydro’s flooding modeling, based on United States Army Corps of Engineers analysis. Flood water then moves southeast through the homes located along Saturn Place and Venus Place, all the way to Lindbergh Boulevard and Grovers Avenue. That’s an area of about four blocks by ten blocks.

“Can you believe it? Two creeks coming together on the site of a superfund site,” University of Pennsylvania Urban Studies professor Michael Nairn asked a group of 11 visiting graduate students and 4 professors from the University of Venice, Italy, right next to the landfill, on Monday afternoon. “You have to ask yourselves, why would the City of Philadelphia site a housing development right next to a dump, on the active floodplain of an urban creek?”

Many houses built as part as the Eastwick urban renewal project in the 1950s have sunk and become unsafe. Many houses have been flooded with more than six feet of water during severe storms.

As part of his research with the Lower Darby Creek Area Research Team, Nairn has been providing data to inform the Lower Eastwick Public land Strategy, a one-year planning process to decide the future of 189 undeveloped and publicly owned land in the neighborhood, anchored in an ecological understanding of the area and its flood risk. Nairn is also an advisor for the Eastwick Friends & Neighbors Coalition (EFNC), which is a key partner in the planning process. When CCRUN was looking for a place to apply its research in Philadelphia, it’s Drexel partner, Civil, Architectural, and Environmental Engineering Department professor Franco Montalto, chose Eastwick. Montalto has an ongoing urban resilience planning exchange program with the University of Venice, and that’s how a group of Italians ended up standing along Cobbs Creek this week.

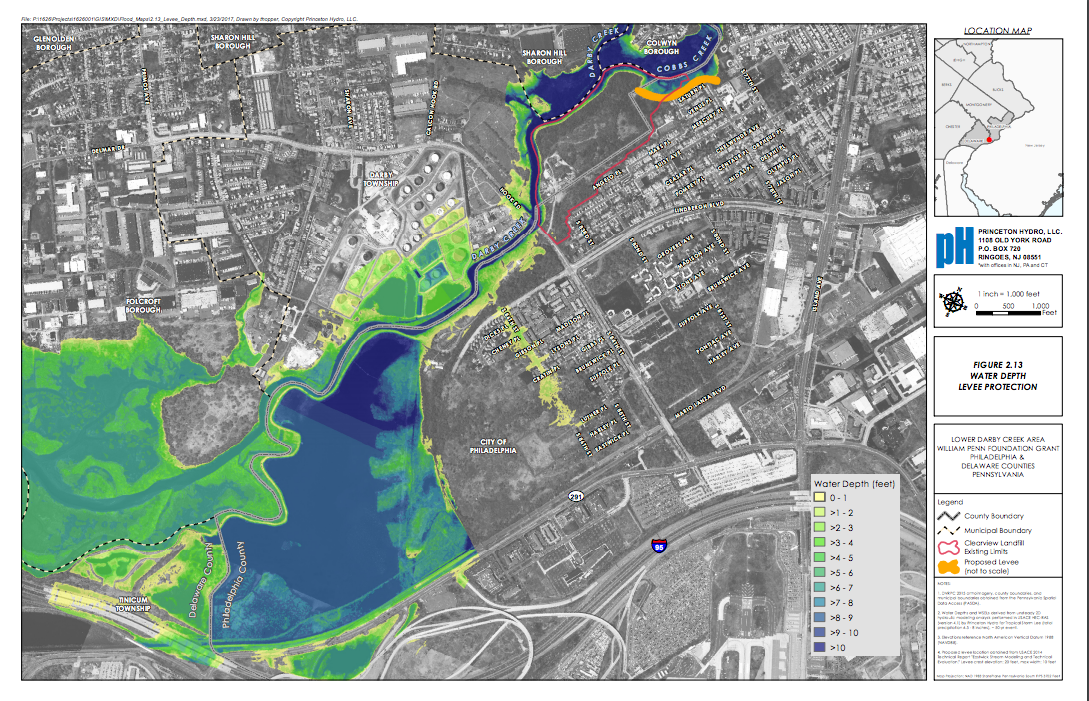

Flood mitigation strategies vary widely; several ideas are being explored by these groups for Eastwick. One such solution that has also been preliminarily explored by the Army Corps of Engineers in recent years is a levee at 78th Street. According to Princeton Hydro’s research, building a levee is the only solution that wouldn’t divert the flood water somewhere else. Scientists are still unclear about what to do with the water captured by the levee, a question that could be solved through a more robust feasibility study. The Army Corps, Nairn said, has requested funding for this study and it could be approved in the coming year.

Even though most of Eastwick’s flooding is caused by water flowing downstream, the neighborhood is also subject to upstream flooding, caused by higher tides and coastal storm surges. When Hurricane Sandy hit Philadelphia, downstream flow of the Schuylkill River and upstream tides from the Delaware River inundated the area along the train tracks up to Eastwick Station on the east, and pushed the Darby upstream on the west, causing an overflow along 86th Street, bringing water 10 blocks east into the neighborhood.

“All the water in Eastwick drains right here,” Nairn told the Venetian students at the former Pepper Middle School site, which is considered the lowest point of Philadelphia. “This has become basically a big pool.”

The Pepper School was also under nine feet of water during Hurricane Floyd in 1999. Experts believe that upstream and downstream flooding worked together, with water coming from the creeks from the west and from the Schuylkill River via the Mingo Creek from the east.

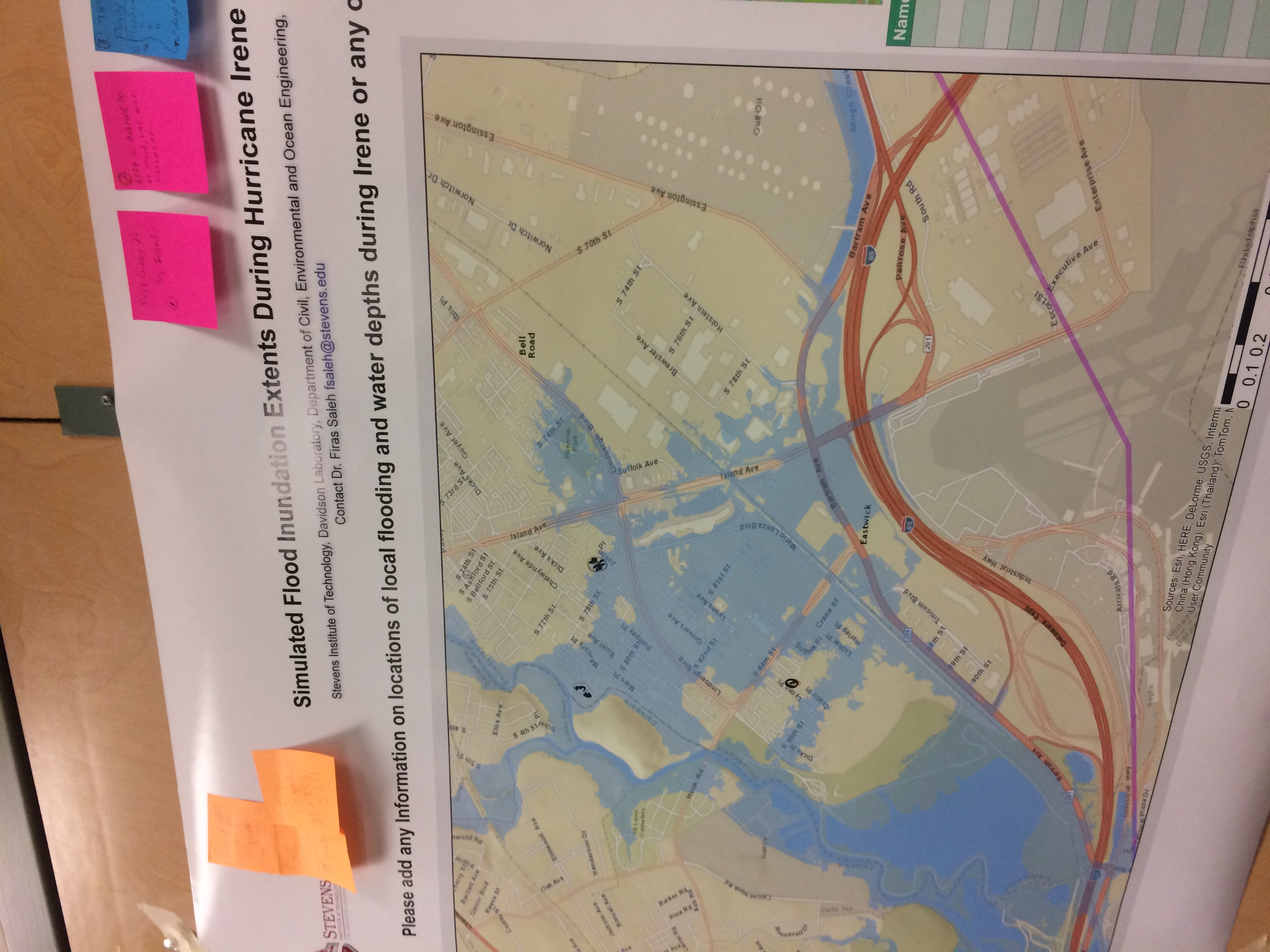

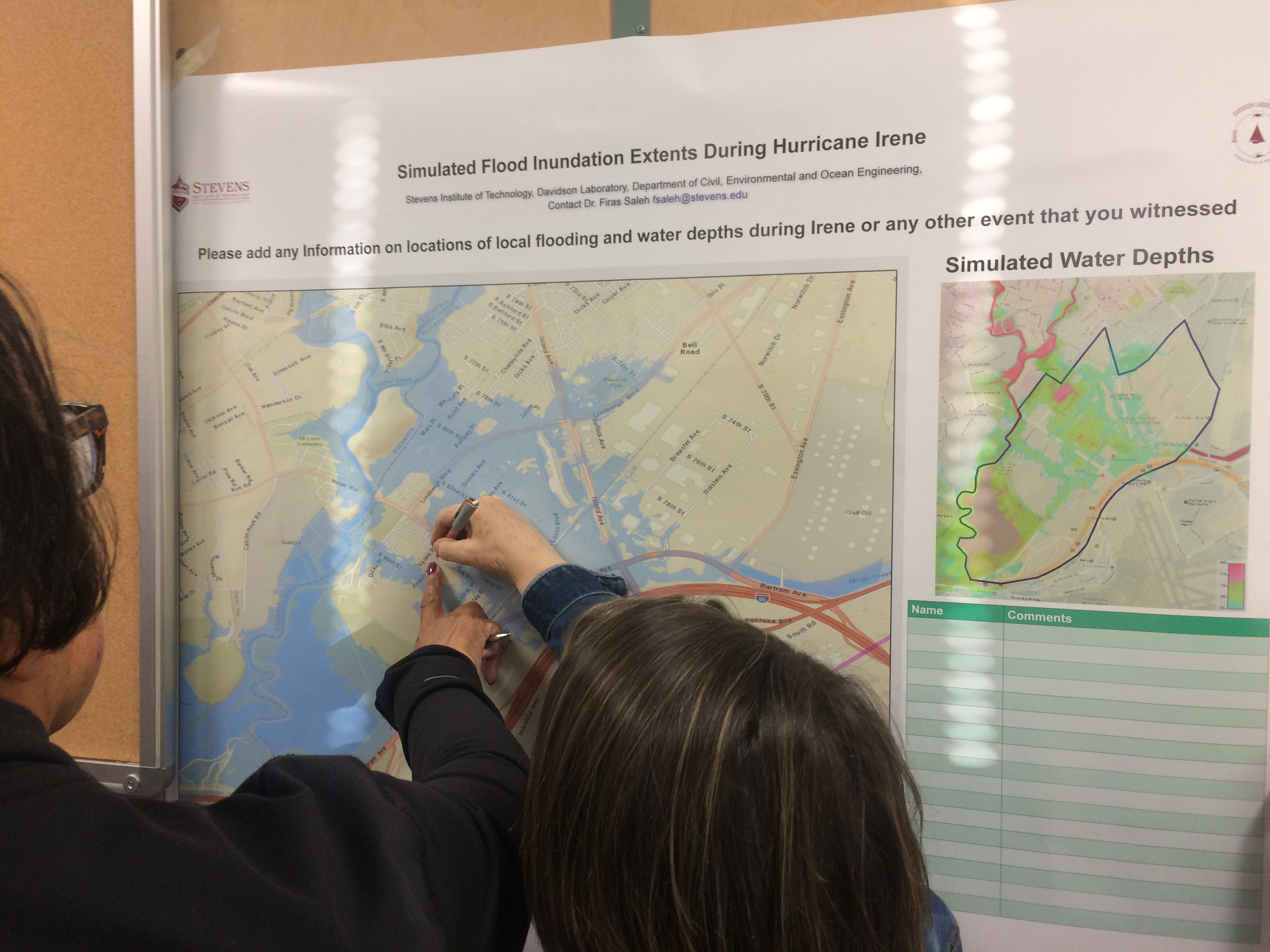

But what would happen in a storm that created severe downstream flooding, like Hurricane Irene’s impact, along with the kind of upstream flooding caused by Sandy? CCRUN’s Stevens Institute of Technology researcher, Firas Saleh, has been developing a model that simulates precisely that scenario.

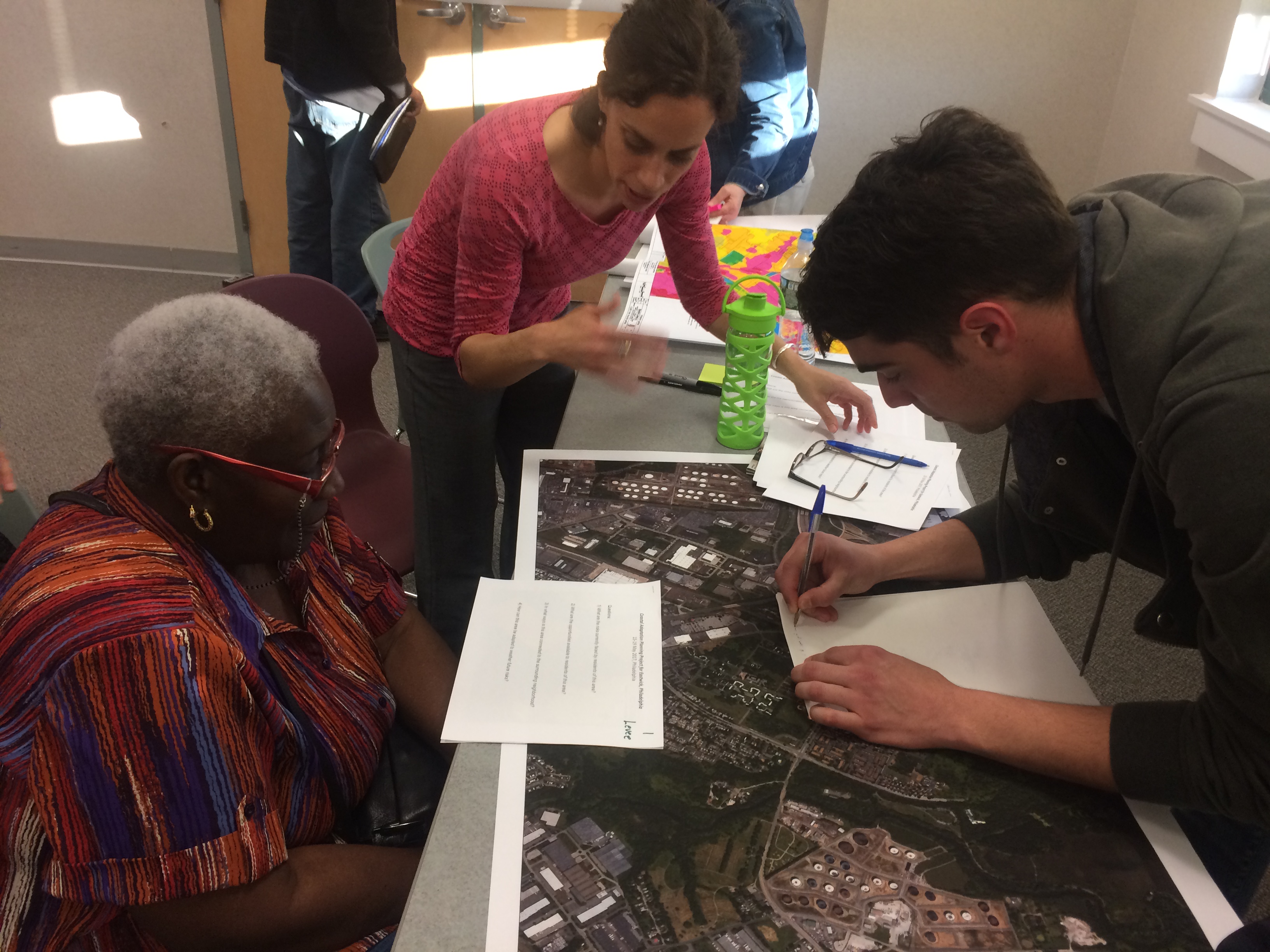

The model was shared with Eastwick residents at a workshop held by CCRUN and the Lower Darby Creek team at the Mercy Wellness Center on Monday evening. With a click, Montalto played a gif simulating the potential flooding: most of the neighborhood was underwater.

“What’s the likelihood that the two could occur together?” said EFNC’s environmental justice chair Joanne Graham.

“It’s difficult to say,” Montalto answered, but given climate uncertainties “this is something that we at least have to think about.”

“I lived through at least three floods, and I was there in 1954 when all 86th Street flooded and folks had to use row boats to rescue people,” EFNC’s Terry Williams said. “So, it can happen.”

One of the workshop’s goals was to get the community’s input on the accuracy of the predictive models. Did Eastwick really flood where model shows it did? A second goal was to demonstrate that water, and the way it works, is complicated. Especially in Eastwick where the area has been extensively modified since European settlement altered the water systems. “Nothing is straightforward in Eastwick,” Nairn said.

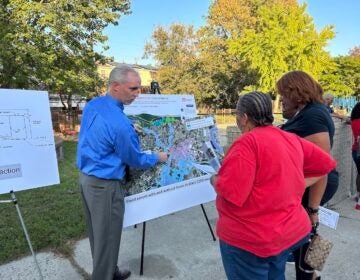

The workshop also introduced coastal adaptation and flood mitigation strategies that could be applied to the planning process in four specific areas. In addition to a levee at 78th Street, researchers proposed a potential forest restoration site at what’s called as the 128 (the acres south of 84th Street), a transit-oriented development at Eastwick Station and an elevated development clustered at the former Pepper School site. Residents broke into four groups, led by the scientists and the students, and discussed what they would like to see at each site.

“Having a levee? Boy, I was down with that,” said Margaret Cobb, a member of Eastwick Lower Darby Creek Area Community Advisory Group. “I like the location of the levee because it is in the green area, so we thought it could blend in with nature.”

“We could have some gondolas,” EFNC’s Carolyn Moseley joked.

If a new Amtrak rail station were ever built at Philadelphia International Airport, that would likely put a new kind of development pressure on land around Eastwick Station. When asked how they would envision that development residents imagined a multi-level parking garage between the station and Penrose Plaza to ease street parking, a tourist center with a cafe on the west side of the tracks, and elevated and sheltered ramps connecting everything.

“No concrete or impermeable materials, native plants, all soil,” said EFNC’s vice president Ramona Rousseau-Reid. “And a trail above it where you could walk, or take a shuttle, from the tourist center to the [John] Heinz [National Wildlife] Refuge.”

Residents were also open to demolishing the former Pepper School, and replacing it with an elevated building that could be used as a model center to demonstrate flood resiliency, bring in some light industry, and give the community a place to meet.

“The reality is that you have to develop,” Graham told an Italian student who asked why building something there if it was such a vulnerable spot. “You need a place to live, you need institutions, you need places to work. It’s an opportunity to develop and at the same time mitigate with sustainable development.”

In an interview a couple of weeks ago, Nairn told PlanPhilly the idea of sustainable development in this context doesn’t sound real to him, because it would be extremely costly and would probably have a short shelf life.

“There’s the right place for everything. People need employment, they need jobs, there’s no doubt about that. But why is that the right place for it?” Nairn said of the Pepper site. “This was a really bad idea in the 1960s, and is a worse idea in 2017. It’s just a bad idea.”

Nairn believes flooding in Eastwick could be managed with a combination of green (coastal forests) and gray (levee) infrastructure. And he’s confident that the planning process will bring solutions to solve the problem. But he says, “we need the right evidence, to solve the right problem.”

Drawings based on the community’s ideas and the Venetian student’s work will be presented on Friday, May 19th, at Drexel University, Curtis Hall, room 351, 5:30 PM. All are welcome.

Irene flooding simulations by Dr. Firas Saleh and his Master student Hantao Guo.

(Credit: Davidson Laboratory of Stevens Institute of Technology)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.