Four reasons why Philadelphia is gentrifying

Should the city’s politicians ever come to a consensus on what to do about gentrification, a new paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia offers guidance on how to address the hotly debated issue.

Gentrification is nothing new, Fed economist Jeffrey Lin suggests in his paper, “Understanding Gentrification’s Causes.” Focusing on Philadelphia, Lin reviewed over a century of census data on U.S. metropolitan areas, tracking decade-by-decade shifts in a neighborhood’s average household income relative to the other neighborhoods in the city.

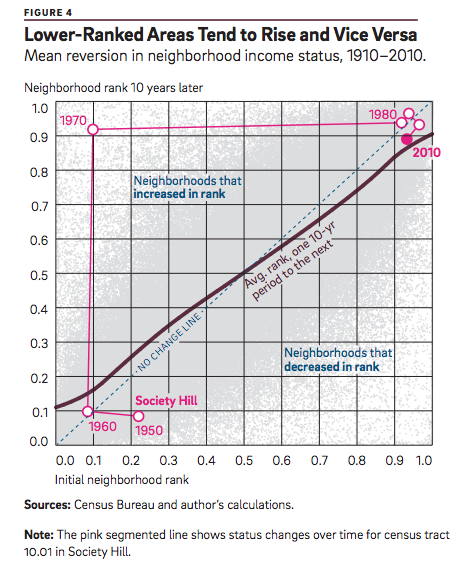

Lin found that rapid neighborhood change is a constant over the Philadelphia’s history. Lin observes that neighborhoods revert to the mean over time: wealthier neighborhoods decline and poorer neighborhoods improve. Dramatic shifts emerge over time: From 1950 to 2010, the percentile income rank of Philadelphia neighborhoods shifted an average of 30 percentile points.

To put it another way: If you divided Philly into 100 neighborhoods and then ranked them richest to poorest, the average neighborhood’s rank jumped or fell 30 points over this period.

Over the short term, most neighborhoods show smaller changes, just six or seven percentile points per decade on average in Philly, and nine points across all U.S. metros.

However, the averages hide the outlier neighborhoods — the neighborhoods we tend to notice most. While some are noteworthy for their steadfast resistance to change — Chestnut Hill has remained consistently wealthy over the years — it’s those that undergo sudden shifts that draw the most attention.

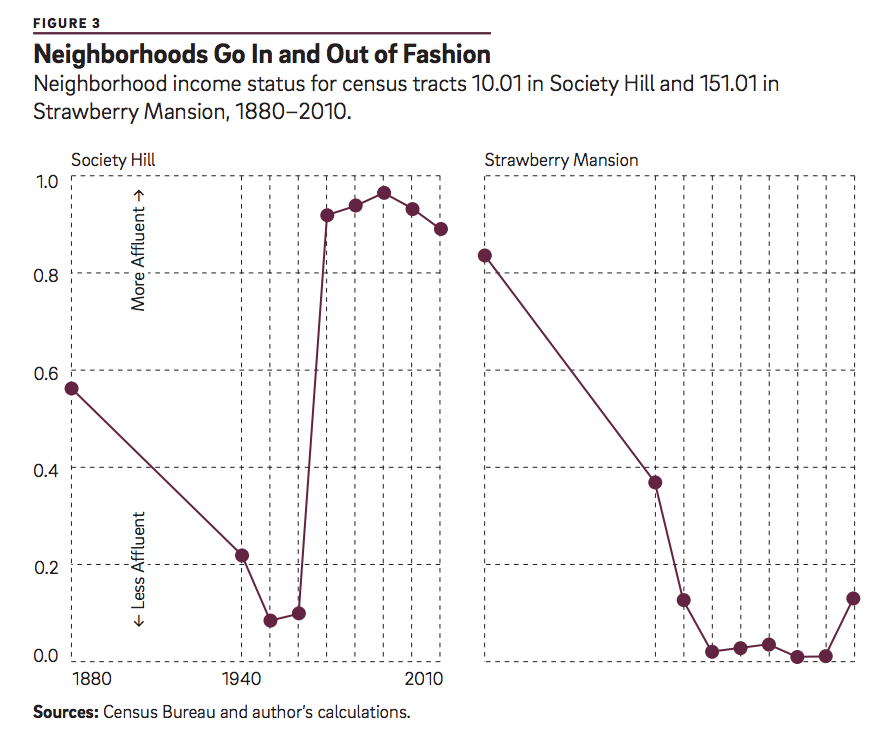

Lin points to Society Hill, which entered the 1960s as one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city, but ended the decade as one of the richest, where it’s remained ever since. On the flipside, once tony Strawberry Mansion fell out of favor during the first half of the 20th century, and only quite recently has shown any sign of recovery.

While neighborhood gentrification is nothing new, Lin said the recent trend of downtown neighborhoods gentrifying is, reversing a long trend of decentralization. “Suburbanization has been happening for a long time,” Lin told PlanPhilly. “One thing that is interesting and distinctive is the extent that people are reversing that century plus trend of moving ever further out.”

“The recent revival of American downtowns is something that, in that sense, is distinctive in history,” he added.

Lin points to four factors — essentially the four things a household considers when deciding where to live — that can cause a neighborhood to gentrify or decline economically: amenities, productivity, access, and prices.

Amenities encapsulates shops, bars, restaurants, schools, parks, and other related things that someone might want to visit when they’re not working. Productivity looks to geographic influences on employment locations — where firms locate, and why. Access considers how changes in transportation infrastructure and technology can shrink or widen the distance between homes, amenities, and jobs. The final factor, prices, considers the natural lifecycle of a neighborhood’s affordability based on the age and quality of its housing stock.

“Changes in even one of these four factors can be enough to transform a neighborhood,” writes Lin. That’s why the familiar, even hackneyed, history of urban decay and subsequent gentrification still rings mostly true. The creation of the interstate highway system actually did encourage white flight by dramatically reduced commute times to the suburbs. Artists really are frequently the first wave of gentrification because they are often the first to invest in a neighborhood after a long period of disinvestment, and their galleries and shops provide new amenities, encouraging young professionals to move next.

What Philadelphia, and other cities, have seen in recent years is a confluence of many of these factors across numerous neighborhoods, causing a widespread reversal in the longer term demographic trend.

“For a long time, people have been trying to get out of cities,” Lin said. “Even as cities were centers of production that attracted millions of people, those with means have tried to escape the congestion, the pollution, the disease.”

Many cities grew in a pattern of the wealthiest citizens continually moving as far from the city’s dirty, dangerous center as commuting technology would allow them.

But in recent years, many of the worst drawbacks to urban living have declined significantly, shifting the pro-and-con calculus. Thanks to pollution regulations, cities aren’t as dirty as they once were. Crime rates have plummeted, while commute times have risen. And thanks to modern medicine and mosquito control, it’s been a century since the last airborne pandemic swept through US cities.

Lin’s paper, and the four factors it identifies, provides elected officials a map for achieving their policy objectives around gentrification. But the how of policy isn’t the biggest hurdle to effectively dealing with the issue – it’s the what: What do we want to do about gentrification?

Most elected officials try to have their cake and eat it too, lamenting displacement and decrying developers while applauding new storefronts and neighborhood population growth. Politicians’ deep ambivalence toward gentrification all but ensures anemic political intervention.

More likely to benefit from Lin’s analysis: real estate developers and investors, who can use the four factor framework to guide their investment decisions.

Most of Philadelphia’s neighborhoods outside Center City haven’t seen a major development boom since the 1940s, when new highways and cheaper cars put the white picket fenced dreams of suburban living into reach for millions of middle class Americans. Forty percent of Philadelphia’s housing stock dates back before 1940, per a Governing study of census data.

Like most things, homes tend to get cheaper the older they are, with the notable exception of the models that are both well-built and well-maintained. Old housing stock provides ample opportunity to gut a rundown interior and replace it with modern elements and fixtures, or simply knock-down the old heap and replace it. So it’s no coincidence that large sections of Philly’s fastest growing neighborhoods like Fishtown, East Kensington, and Point Breeze were built before WWII.

Developers could next consider changes to a neighborhood’s amenities. In some places, developers have invested in amenities like neighborhood bars and coffee shops to create self-fulfilling prophecies of gentrification. Consider John Longacre with his bars in Point Breeze or Ori Feibush with his OCF coffee shops. Feibush has also made a dramatic show of cleaning up vacant lots near his properties, not just adding an amenity, but drawing media attention in the process, effectively advertising the neighborhood to potential residents and investors. A neighborhood school’s reputation can make or break the local real estate market.

In terms of access, a few changes on the horizon could portend significant changes. SEPTA is currently considering a complete overhaul to its bus route systems. Some neighborhoods may see their bus services reduced, which would militate towards decline. Others may see transit services increase, improving access to job centers by effectively reducing commute times by cutting the wait time between buses. All else considered, that would make the neighborhood more desirable, raising home prices and rents.

Perhaps more dramatically, but certainly less certainly, the advent of autonomous vehicles will affect neighborhood access. Lin argues that as income levels continue to rise, driverless cars will reduce the opportunity cost of long commutes by allowing passengers to engage in work or leisure activities. In layman’s terms: driving is a pain, and driverless cars will take away that pain and let you either get a jump on the day’s tasks or flit away time on your phone.

In the past, most technological changes reduced the opportunity cost of commuting by making it faster, thereby allowing for longer commutes and decentralized growth – horse-drawn omibuses and then trolleys created the streetcar suburbs like West Philly and Germantown; Pennsylvania Railroad’s main line out to Lancaster and beyond sprouted the Main Line; the Interstate Highway System made doable daily commutes from Chester County to Center City. Robot cars will reducing opportunity costs by allowing commuters to focus on other tasks.

Some urban thinkers think autonomous vehicles may not have the same impact as previous transportation technological shifts. For one, autonomous vehicles may develop in centrally owned fleets, like taxicabs, rather than individual owners. In other words, imagine a world more like New York City, where individual car ownership is relatively rare. Given the reduced labor cost from not having a driver, the marginal costs per trip would drop to just fuel and maintenance, making it cheap enough to rely on for daily commutes. At the same time, the city could dramatically reduce the amount of space it sets aside for parking, making cities denser and more vibrant still. Parking lots could be replaced by actual parks. Add in the promise of electric cars, and city air quality might dramatically improve.

While commute times have steadily risen over the past twenty years, this alone can’t explain the shift away from long drives to work towards short walks. A rise in median household income would explain the change — the more you make, the more being stuck in traffic costs you, at least theoretically — but wage levels have remained essentially stagnant for decades.

The paper also points to evidence suggesting that preferences have changed. Millennials appear to care more about amenities than prior generations. This maybe because they’re holding off on marriage or kids, and thus more interested in spending time at bars, shows, and restaurants. Or it maybe that they’re so addicted to their smartphones that going 30 minutes without them to drive to work is unbearable, or some other reason. Regardless, if that preference shift is real — and if it continues through to the next generation — then, even if driverless technology encourages decentralization again, cities might not empty out the way they did during the Postwar period.

“The best evidence,” Lin said, “points to a real change in people’s preferences.”

Changes in productivity are perhaps the hardest to predict in advance. Lin points how changes in work changed desirability of certain neighborhoods. Manayunk first boomed thanks to its proximity to the Schuylkill, which powered its garment mills. When that industry shifted to the South, and then abroad, Manayunk declined. In time, however, its proximity to the river and cheap, old housing stock once again fueled its recovery as a lively nightlife and retail cluster along the river with nice views from up the hill.

In recent years, cities have benefitted from agglomeration effects – the desire of firms to cluster close to both potential employees and potential customers. In simple economics, such clustering would mean increased competition for the same workers, increasing labor costs, customers, reducing revenues. But if extra workers and customers are attracted to a region because there are so many firms there, those firms collectively gain despite the nearby competitors.

Agglomeration effects are more pronounced in high-skill sectors, where labor has a relatively large impact on productivity. That’s why so many sectors tend to cluster in a few cities – tech in Silicon Valley, banking in New York, film production in Hollywood. But they can also make a noticeable impact by simply clustering customers who are looking for choices, which is why so many bars line Main Street in Manayunk.

Naturally, there are limits to the four factors’ predictive powers. Throughout history, seemingly spontaneous, external changes, beyond the control of local leaders, have left indelible changes in the urban landscape. Philadelphia was once the nation’s hub of shipping, commerce, and banking, but it lost its premier status to New York City as newer, larger ships required deeper harbors, the Erie Canal opened, and the Second Bank of the United States closed.

Both in his paper and in person, Lin hesitates to opine the future, other than to say that change is unavoidable.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.