Displaced by Hurricane Maria, Puerto Ricans move to Philadelphia

Taina Gomez saw no other option.

Over a month ago, she lost everything to Hurricane Maria. Her house near the beach in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, was completely destroyed. Also gone was the hospital where she received treatment for a problem with her colon.

“I had to come here to have a better chance to live,” Gomez, 37, said in Spanish. “Until Puerto Rico recovers, you can’t be there if you have a medical condition. There’s nothing — no doctor, no way to communicate, nothing — it’s completely devastated.”

Family in Philadelphia took her in, but they didn’t have room for her 18-year-old daughter. She was sent to live with her father in Florida.

“I lost it all, all,” Gomez said. “Starting from zero — it’s hard.”

In the weeks since Maria devastated the U.S. territory, thousands of Puerto Ricans had been forced out of the island. With no power, no water, no medical assistance, no school, and no jobs, many see no other choice but to leave. And many of them are coming to Philadelphia, home to the fifth largest Puerto Rican population in the country, at 121,643 according to the 2010 Census.

Hurricane Maria is just the latest in a string of natural disasters that have struck with ever-increasing frequency, and which have placed additional burdens on local governments — not just those directly impacted, but by the safe havens that take in thousands of people left displaced and dislodged of all worldly possessions by these storms.

Philadelphia Councilwoman María Quiñones-Sánchez, whose 7th District includes some of the city’s largest concentrations of Puerto Ricans, said she gets about a dozen calls a night from constituents who are bringing their family.

“I would venture to guess that about half of every daily flight from American Airlines is coming with people who are coming to stay temporarily or are really seeking some sort of refuge until the things in Puerto Rico normalize — whatever the new normal is going to be there,” said Quiñones-Sánchez, who herself moved to Philadelphia from Puerto Rico as a child.

To help those displaced by climate adapt and connect them with FEMA and other city services, the Philadelphia Office of Emergency Management opened a disaster assistance center in the offices of HACE, a Hispanic community development organization on Allegheny Avenue. Nine days after opening, the center had already received 233 people displaced by Maria, 110 of which were families.

Gomez said the assistance center was very helpful.

“They offered to help me with food, housing, and medical attention, which is what I care the most,” Gomez said in Spanish.

Elena Alvarez Díaz, a 47-year-old Puerto Rican who also moved to Philly after the hurricane, said getting a job is her most urgent need.

“If I don’t start working, I get depressed,” Alvarez Díaz said at the OEM emergency center. “My North [Star] right now is to get a job and start with my life again.”

Alvarez Díaz had it a little bit easier. She lived in San Juan, Puerto Rico’s capital and largest city, which is in a slightly better condition than the rest of the island. Still, her neighborhood was half destroyed and she lost her work in the island’s incipient medical marijuana industry — the crops are gone.

“There was no water and no electricity, and food was very scarce; so it was very hard to be there,” Alvarez Díaz said. “I decided to see if I could leave — and I have some friends here — so, I came.”

Councilwoman Quiñones-Sánchez said Puerto Rico was already losing 10,000 people-a-month to the mainland U.S. diaspora before the storm. Now, she thinks that number is going to grow exponentially. Quiñones-Sánchez said there’s no official count of how many are already in Philadelphia, but worries that too many are coming in what she calls “crisis mode” — with no plan and no family or friend connection — and will need housing, food stamps, and health services.

“We are a little scared about what that means because Pennsylvania doesn’t have a budget, FEMA doesn’t have a budget — to determine what kind of assistance [we can give] past the crisis mode and we have a long list of people on affordable housing list.”

Joanna Otero-Cruz, deputy managing director for community services in the Philadelphia managing director’s office, is also worried because the city is not getting any assistance from the federal government to host Puerto Ricans displaced by the hurricane. FEMA has a public assistance program that reimburses local government and states for disaster-related services, and was granted to Houston after Katrina.

“A lot of the FEMA benefits are still not lifted — meaning they are not getting granted — which restricts [the ability of] our people in Puerto Rico and … here to get the services that they are entitled to,” said Otero-Cruz.

NEW CLIMATE EVENTS, NEW EMERGENCY RESPONSE

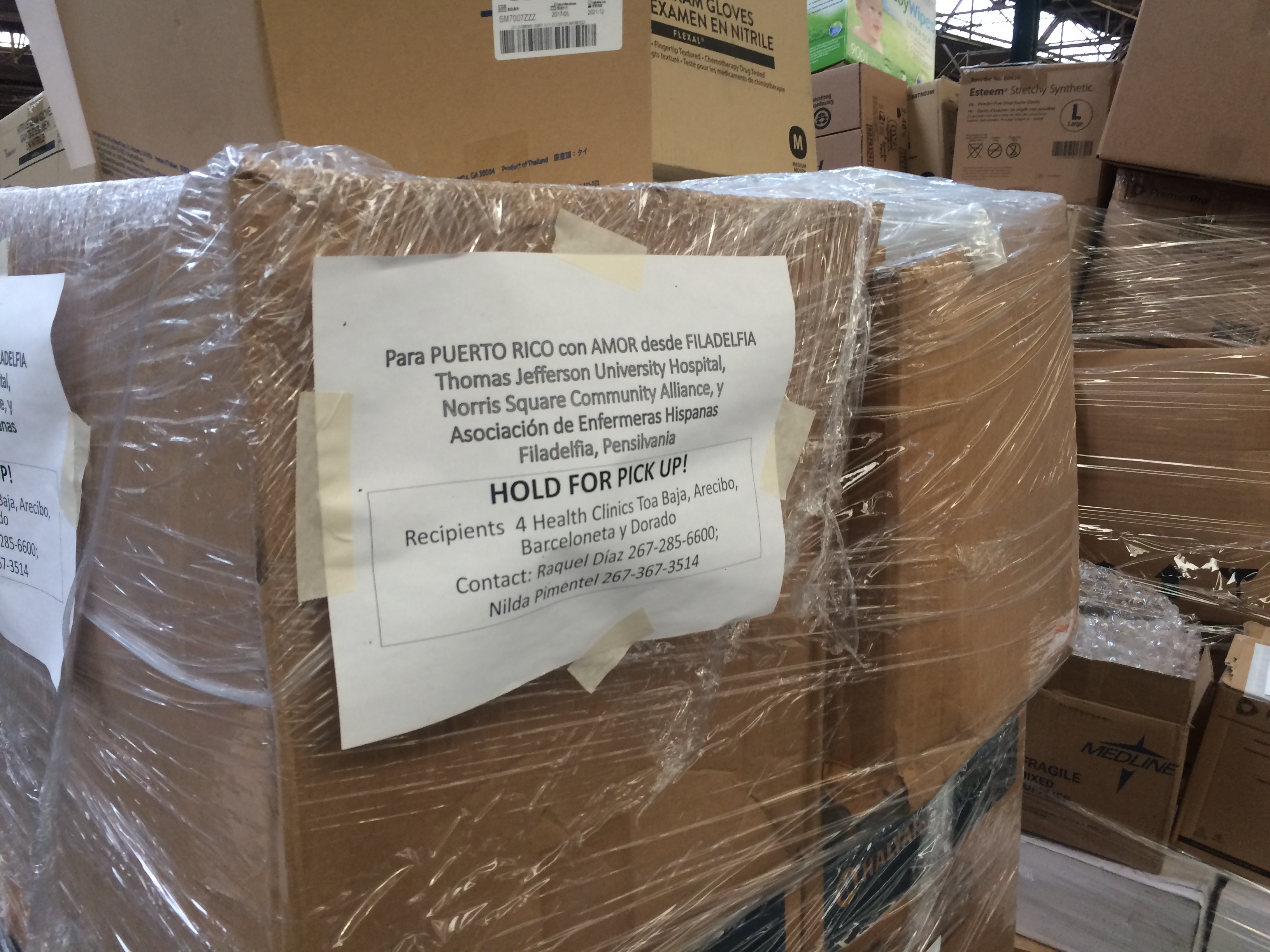

Madeline Neris Negrón has been sorting donations in a huge warehouse in North Philadelphia for weeks. The warehouse is the hub of Unidos Pa’ Puerto Rico, a grassroot organization created after Hurricane Irma hit Puerto Rico. The group was organized by Quiñones-Sánchez , along with Pennsylvania state legislators Angel Cruz and Emilio Vasquez. As of October 20th, the group had raised over $200,000 for hurricane relief.

Over the last few weeks, Philadelphia has sent about 800 pounds of supplies to Puerto Rico, Negrón said. Negrón and other volunteers have been making care packages with food and supplies to last a week, for a family of four, and sending them with people flying from Philadelphia to the island to help their families.

Negrón said her husband, Víctor, is there now and tells her the situation is unbearable — it smells bad, there are dead animals everywhere, stagnant water, mosquitoes that can carry dengue and zika, no clean water to clean your hands, no medication, and no food. So he’s bringing back their 18-year-old son, who was studying in Puerto Rico, and his mom.

“If we can get them the supplies, if we can get them the resources, if we can get them the tools that they need to build on their own, they wouldn’t have to migrate,” Negrón said while sorting supplies. “But because it’s getting so long to get to them, it’s taking so long to get them the help that they need, they have to leave. It is life or death for them.”

Negrón worries about who will rebuild the island if so many flee to the mainland. She wants local representatives here to ask for help from the federal government.

“Either we’re going to take care of them on their island or you’re going to take care of them here,” Negrón said. “One way or another, they have to be taken care of.”

Geoffrey Dabelko, director of Environmental Studies at the George V. Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs at Ohio University, studies the complex connections between environment, population, conflict, and security.

Climate change, he said, is forcing local governments to fundamentally shift the way they think about an emergency response. Even when those emergencies happen outside their cities.

“The people are going to move,” Dabelko said. “And if we have immigrant communities from different parts of the country, [and from] around the world, that’s going to mean that they’re going to be turned-to as support.”

Although migrations are caused by a complex series of socioeconomic and political factors, Dabelko said we are going to see more migrations triggered by climate.

“It is not that climate change causes them to move because climate change doesn’t cause a single storm,” Dabelko said. “But it can make them more intense, and so the impacts of those storms are more severe, causing more people to move.”

And people often move to places where they have family or friends.

“Those communities living outside the specific area often are critically important to helping friends and family at home recover,” Dabelko said.

Dan Bradley, director of Philadelphia’s Office of Emergency Management, said this is not the first time the city is helping people being displaced by a climate event — some came after Katrina — but that these events do make him think about the roles cities can play in larger disasters.

“It does raise some questions because this is happening outside of the normal disaster process where, really, our mission is for Philadelphia to respond to emergencies here. We’re perhaps blazing a new trail.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.