A new plan for Chinatown

Philadelphia’s Chinatown is a mere 0.3 square miles, a postage stamp community that nonetheless enjoys an impressive purchase on the city’s psyche. As Center City booms around it, this little ethnic enclave is changing radically. To help its residents adapt to the new day, Chinatown’s most prominent civic group just released a comprehensive plan for the neighborhood’s future.

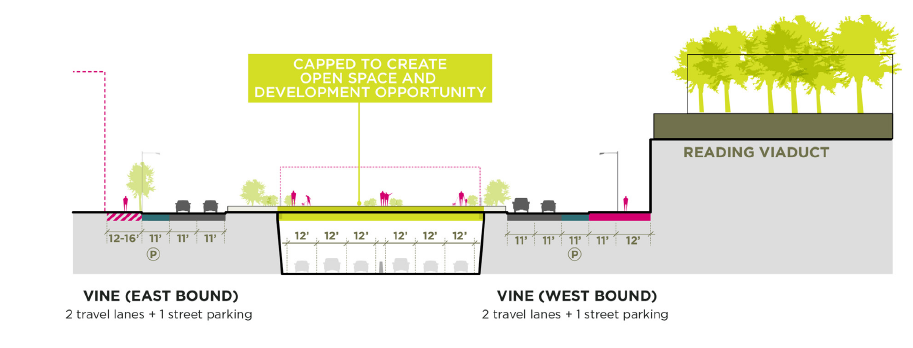

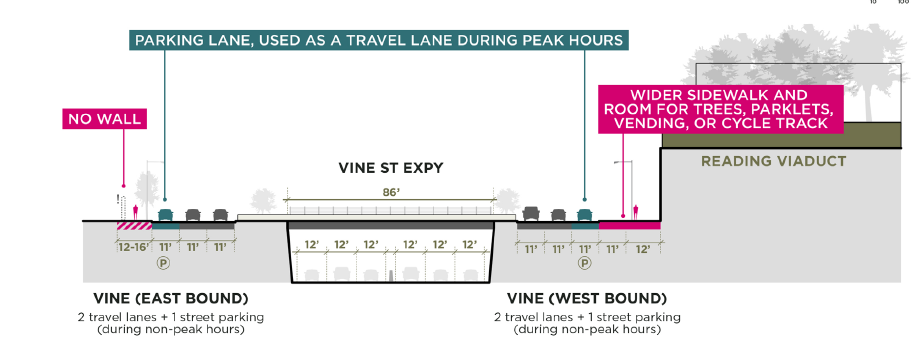

Founded in 1969 to oppose a proposed route for the Vine Street Expressway that would have destroyed neighborhood landmarks, the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC) is one of the city’s most sophisticated community groups. In addition fighting such existential perils, it engages in more quotidian planning and zoning efforts, including the new report released this week.

“Chinatown is a neighborhood that is constantly changing and adapting in order to survive,” said Sarah Yeung, director of planning for PCDC. “The key is to strike a balanced approach while at the same time not letting go of our values, which is to allow for community self-determination and to create an equitable community.”

Funded by the Wells Fargo Regional Foundation, this is Chinatown’s first comprehensive plan since 2004. Some concerns remain constant. Affordable housing is one of those necessities that is never fully addressed, especially in a neighborhood with scarce land and a steady stream of newly-arrived, often lower-income, immigrants.

The 2017 plan pays greater attention to the need for green space and safer access to available parks. Preserving the neighborhood’s light manufacturing sector is another new priority in the 2017 plan.

For years, the area north of the Vine Street Expressway, now most commonly known as Callowhill but considered Chinatown North to many, hosted many small factories and warehouses servicing the historic neighborhood’s many restaurants.

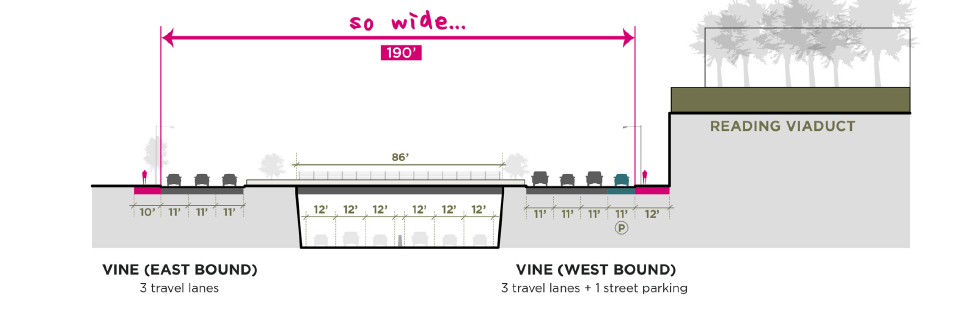

“Connecting Chinatown North to the historic core has always been the challenge for this Chinatown,” said Kathryn E. Wilson, Associate Professor of History at Georgia State University and author of the 2015 book Ethnic Renewal in Philadelphia’s Chinatown. “There was always Chinatown North [of Vine Street], but the expressway really cut off the top part of that community. A lot of what neighborhood planning has done since then is try to bridge that.”

That challenge is different than it used to be. Callowhill is undergoing a renaissance. The increasing number of old factories and warehouses being converted into condos and apartments, has led some developers to aspirationally call it “the Loft District.”

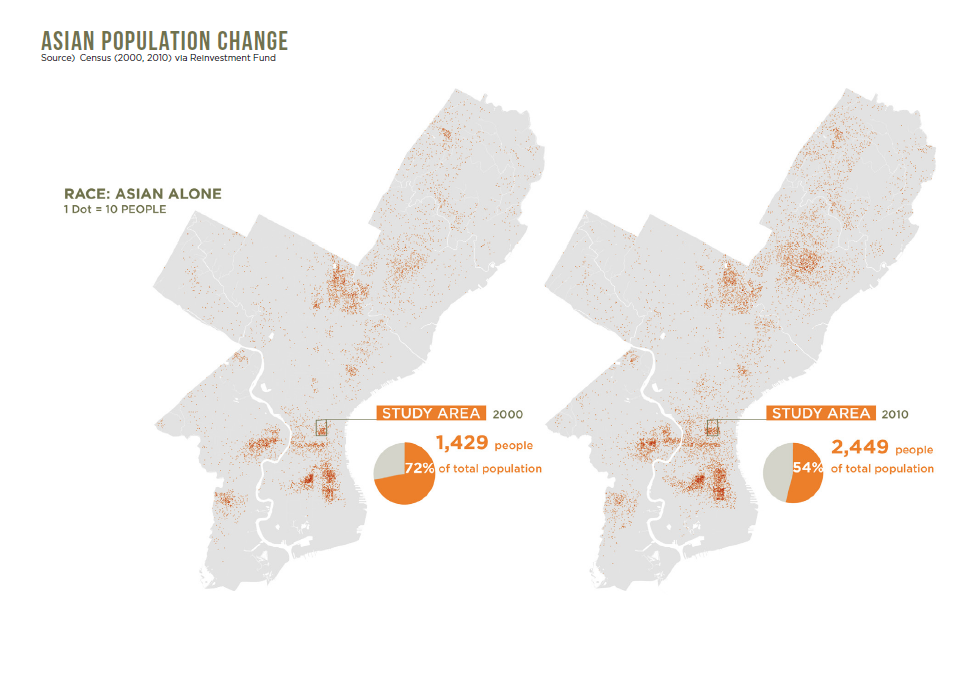

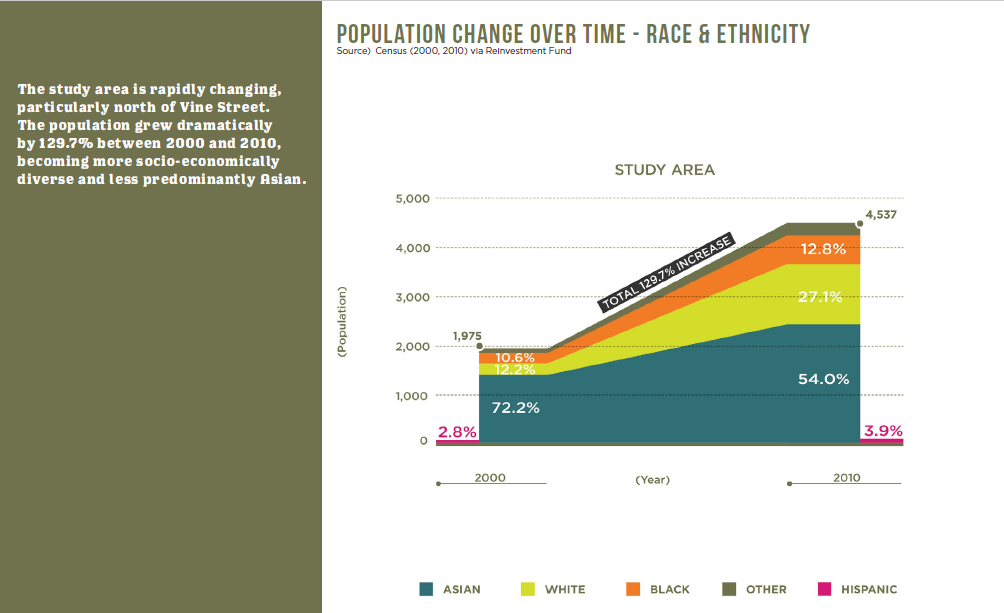

And that’s just one of the many dramatic changes to Chinatown documented in the report. Between 2000 and 2010. Chinatown’s population spiked from 1,975 to 4,537. Although it is still majority Asian, the percentage fell by 18.2 percent to only 54 percent, while the white population grew by 14.9 percent. The Chinese immigrant population, meanwhile, has diversified with an emergent Fujianese population and numerous dialects becoming evident beyond Cantonese (which has historically dominated Philadelphia’s Chinatown).

Many of Chinatown’s working and middle-class residents have moved to other parts of the city, while the relatively well-to-do and the extremely poor have grown as a proportion of the population. (Twenty-two percent of households in Chinatown live on less than $15,000 a year.) In 2002, 21 percent of employed people living in Chinatown also worked in the neighborhood. In 2014, that dropped to 9 percent.

As housing costs have increased, many residents have moved to other neighborhoods farther away from the high land values of the Center City core. The lower Northeast is home to a large residential hub of Chinese-American residents, and a smaller concentration is found in South Philadelphia.

But even though many people of Chinese descent have left, Chinatown remains still the community’s hub, in large part because of the concentration of services and businesses that cater to Chinese-language speakers. The newer residential neighborhoods are not large enough or established enough to compete.

“A role of Chinatown is as a home away from home for a lot of folks,” said Yeung. “People will come to Chinatown multiple times a week because they don’t have services in their other neighborhoods in their own languages.”

In cities like New York, San Francisco, or Los Angeles — where the Chinese populations are far larger — the historic Chinatown is but one ethnic enclave among many. Satellite Chinatowns, with their own business cores and social services, have sprung up in other locations like Monterey Park in Los Angeles County or Sunset Park in Brooklyn.

But although Philly’s Chinese population is long established, it still isn’t big enough to spin off independent enclaves in other parts of the city or region.

“For Philadelphia, Chinatown is still the center,” said Wilson. “The satellite areas are residential with some commercial development but you don’t see a whole other center of activity, at least not yet. Philadelphia doesn’t have enough of a critical mass to have that take place.”

That’s partly why the PCDC wants to find resources to create new affordable housing or preserve and repair what already exists. Chinatown essentially still serves the function is always has, serving as a landing pad for newly arrived immigrants who can establish themselves and then quickly move on to cheaper neighborhoods. Half of Chinatown’s residents have lived in the neighborhood five years or less.

Asked how PCDC hopes to create new affordable housing in an area with a vacancy rate of just 7 percent, Yeung says that the organization hopes to make use of community benefits agreements in some of the new development that will soon populate the remaining empty lots and parking facilities.

The plan concerns itself with an array of other projects as well. A business improvement district is planned to ensure that Chinatown doesn’t just become a restaurant destination, but retains some of its shopping and service oriented that cater to immigrant groups unlikely to find service elsewhere. Traffic calming measures are desired around Callowhill Street and Vine Street. PCDC wants to see parklets installed on underutilized stretches of pavement and a pilot street vending program at the 10th Street Plaza, a tentative expansion of the crowded restaurant district northward.

It’s unclear how many of these lofty goals will be accomplished. Fighting to preserve light industrial uses north of the Vine Street Expressway will be a challenge, and building affordable housing is never easy. But Philadelphia’s Chinatown has a 120-year history of surviving and thriving, often against all odds.

“People have been talking about how Chinatown was going to be displaced since the 1920s in Philadelphia,” said Wilson. “Always survived and on its own terms. Planning and development one way and activism another. That sense that it isn’t just themed space, it’s a real community, that’s why it survived.”

Dear reader, this article is made possible thanks to your support. Please help ensure that PlanPhilly can provide hyperlocal public interest journalism next year by making a tax-deductible donation during our once-a-year membership drive. When you make a gift, you’ll be automatically entered in a drawing to win a private tour of one of Frank Furness’s earliest commissions, slated for a $4.5 million restoration effort. You will also automatically be entered in a drawing to win an annual membership for the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.