Q&A: Dutch artist Jeanne van Heesjwik, on her time in Philly

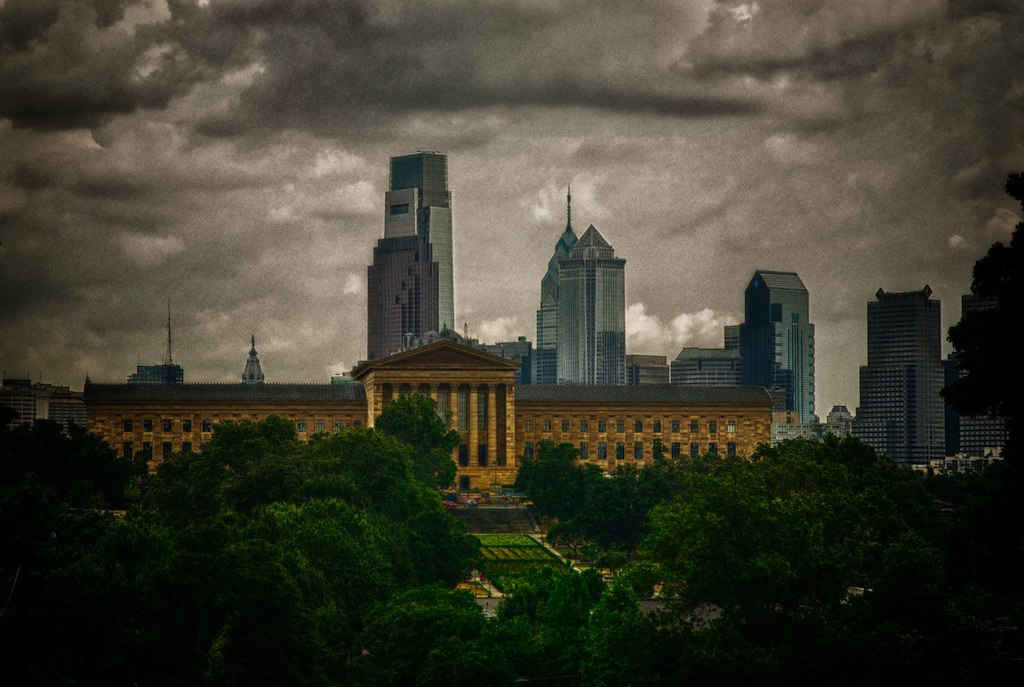

After four years of preparation, dialogue, collaboration, and performance, the Philadelphia Assembled exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art will come to a close on Sunday, December 10th. The project is an artistic attempt to take the pulse of the city through conversation about the challenges it faces.

The curator of these conversations, and the woman who started this whole process nearly four years ago, is Dutch artist Jeanne van Heesjwik.

Van Heesjwik is internationally renowned for her art focused on hyper-local communities. Her mission was to illuminate that average Philadelphians face, in the “City of Neighborhoods,” and form a collaboration that allowed the city to confront those issues in a united fashion.

PlanPhilly caught up with van Heesjwik recently to discuss how she feels as her project comes to an end. We talked about her experience with the city of Philadelphia, how she’s seen it grow, and where she sees it going.

Q: What is the project?

Philadelphia Assembled is a project that I’ve been developing over the last four years with over 150 people from various communities, neighborhoods, and organizations. We have been collectively ideating about acts of resistance, and acts of resilience, in Philadelphia. Where are people actively trying to create a more just future? That’s the short version.

Q: What’s the long version?

[I asked participants] What is the spirit of Philadelphia, what’s changing in Philadelphia? What does that look like? What are the ideas for the future of the city? During these conversations, whenever a person finished, I asked them to bring me to someone else they thought I should meet.

I was passed through a network, sent to different sites and places. Most of these conversations were in people’s houses, in people’s kitchens, in people’s gardens. Certain themes, certain topics kept recurring around vacant lands, food production, food deserts in the city. Words such as self-determination, cooperative economies, unity, and freedom kept popping up. In all of these conversations there were actually words like “sovereignty.”

Sovereignty became one of what we now call our atmospheres, [which are organizing principles that] bring together in a word cloud what we got from our conversations. We have five of them: “Sovereignty,” “Reconstructions,” “Sanctuary,” “Future,” and “Movement.” From the very beginning I decided to invite seven other people to form with me what we call an artistic team to help build out these atmospheres. And each atmosphere has a working group of around twenty-five people who, for a year and a half, have been tasked with defining that atmosphere.

We then decided what we would bring to the third phase of the project, which is where we bring together a portrait of Philadelphia at this time. And we’ve done that through this big city panorama, seen through the lenses of our collaborators and their local, national, and global histories. Their act of resilience and resistance, the acts of life that are happening in the city. All of this demonstrated through maps, through drawings, and then through the exhibitions in the galleries. Now the whole ground floor of the Philadelphia Museum of Art is basically a stage where the city is performed.

Q: Where did this idea emerge from?

The seed came from an invitation from Carlos Basualdo, the museum’s curator of contemporary art. He asked me as an artist working in socially engaged art if I, through the lens of my practice, would like to work on thinking about the relationships between an institution such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the city itself.

Q: You’re from Holland, but you’ve spent the last couple years in Philly. What have you learned about the city?

The work is Philly and thinking about the city. And not alone, but with a massive amount of people who are knowledgeable about how its changing. First let me say that I really like Philadelphia. But the city is changing at a dramatic pace. Areas such as Fishtown, Kensington, Point Breeze. They bring up a lot of questions about equitable development. Making sure that people have the right to have a say in the way their daily environment is shaped, in government.

What I do find interesting is that there are interesting models developed here, interesting work around creating viable alternatives. Like, for instance, a group like Urban Creators who have a farm in North Philadelphia where they actually work with predominantly youth of color to think around farming to bring fresh food back into the city. This goes hand-in-hand with the reclaiming of vacant lands, hand-in-hand with environmental racism.

We know the cooperative economy, the form in which people exercise it, that creates new models. This creates new models that can be tested and looked at and adapted to other situations where needs may be different. I see a lot of that in Philadelphia.

Q: There are a lot of these groups, but there’s a question about whether or not they can make a big change. Philadelphia has had for quite some time all these different groups trying different things, but we still have the highest poverty rate of any major city.

It’s a big problem. One of the other traits of the city is there is a lot of segregation and segmentation. They say Philadelphia is the city of neighborhoods, but sometimes it is very confined.

Through the lens of our atmospheres, we had a lot of groups at the table that normally would not be at the same table. The work of trying to constantly connect different places, and create new alliances, I think that’s very important.

There’s this saying that I very much like, “When spider webs unite, they can tie up a lion.” I like that as a quote, but I’m not naive about the fact that maybe all these little struggles will never manage to create enough collective critical mass to overthrow a system.

But I do believe these small exercises are forms of collective learning, training a muscle that when it is the time to connect could be a very strong muscle. I urgently believe things need to change. I also know that it is not going to be overnight. That to me doesn’t make the struggle less important. But I do think it makes it essential to take time to build connections. We need to take time to collectively work together.

Q: What have you learned about the city, its people, and this moment in history?

There’s a lot at stake at the moment. I think it’s extremely important that we come together a much as we can and try to keep pushing for cities that are livable for all. Cities that are not going to segregate more with wealth equality. In Philadelphia, inequality is rising and people are being pushed out. That’s happening everywhere. In Philadelphia it happened later, but Philadelphia could still fall apart.

Q: Few cities responded well to challenges of growth. The only ones I know that have had a decent hack at it are Vienna and Vancouver. Both have decided at a broad level they would invest in affordable housing in an inclusive manner. Our challenge is our affordable housing is expensive to build.

There is this notion of systemic displacement which is inherent in the way American city and society works. In our atmospherics we considered questions of mass incarceration with gentrification. This was weird at first, to look and see how to break communities apart in one way and how that can speed up gentrification.

Housing and security is a big thing in Philly, maybe because people are without work and can’t pay rent or can’t pay taxes. Or when a family member is incarcerated, income goes away. So communities are broken apart. Affordable housing is one thing, but we also need to think holistically about how to develop without displacement. City council is thinking about making affordable housing mandatory. right?

Q: Inclusionary housing. But they are talking about adding only 300 units over four years. That’s not a lot. We need 85,000. That’s how many people are on the waitlist.

We have members in our working groups that disagree on many things. We looked at South Kensington a lot. You know what’s interesting about gentrification in South Kensington? It’s slower. What is the point where it becomes bad, and where is it still ok? The people who arrived at the beginning moved to not so great a neighborhood because they had no money and they helped to make the area better. So when is the moment when we see it as problematic versus where it is when people are just starting to make it a better neighborhood?

Q: In these neighborhoods, no one’s upset to see the first developer. And then at a certain point the scales tip.

There are levels of displacement and it’s a continuous process ingrained in how we think about growth. That’s why I talk about how important the image is–it’s of the utmost urgency that we create images in which we show an alternative.

Hi there, read PlanPhilly often? The news that you read today is only possible because of your support. Please help protect PlanPhilly’s independent, unbiased existence by making a tax-deductible donation during our once-a-year membership drive. We cannot emphasize enough: we depend on you. Thank you for making us your go-to source for news on the built environment eleven years and counting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.