Wage gap divides city workers along racial lines

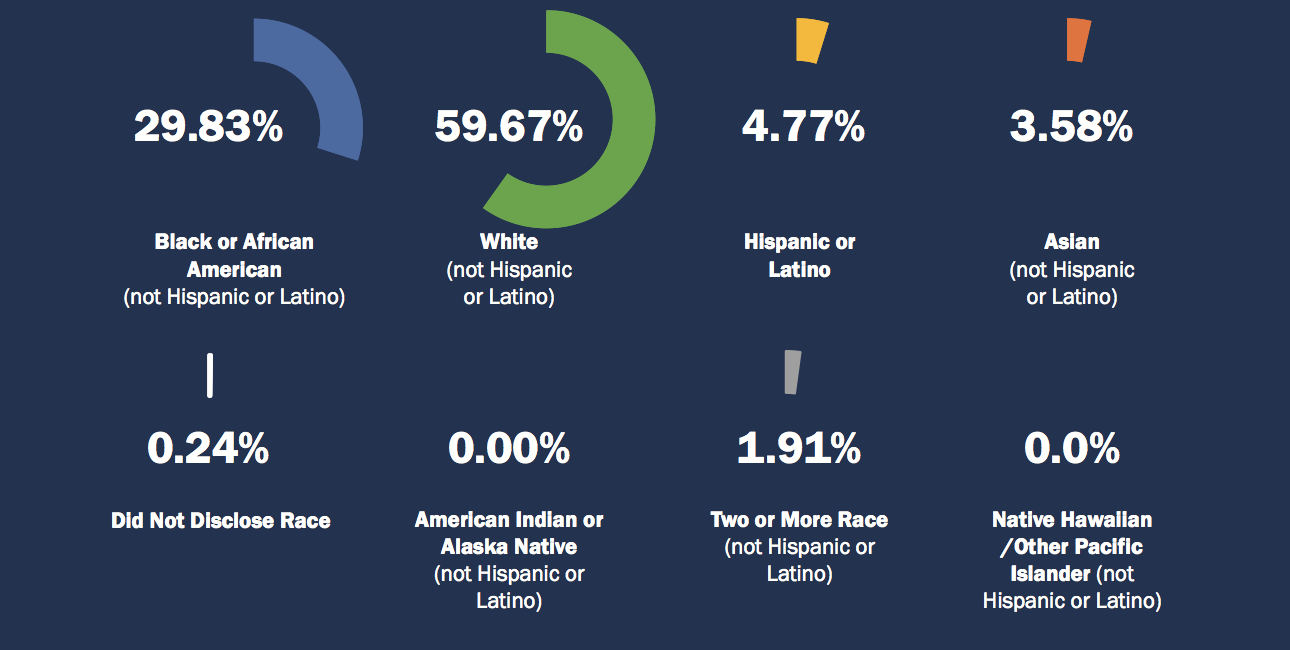

Philadelphia’s municipal workforce overrepresents the city’s large white and African-American populations, a new report shows. But the city’s most desirable, high-paying posts are disproportionately filled by white people.

Men are massively overrepresented in the general workforce, comprising 47 percent of the city’s population but almost 62 percent of its municipal workforce and just over 50 percent of the positions earning more than $90,000 a year.

At a time when the city’s Asian and Hispanic populations are growing, both groups remain underrepresented in city government. Fourteen percent of the city’s population identifies as Hispanic or Latino, but they constitute only 6.7 percent of the workforce. Asians represent 7.20 percent of the population and 3.20 percent of the workforce.

The administration’s goal is to have the 27,582-person workforce more closely reflect the city’s 1.6 million population and to close a persistent wage gap between white workers and everyone else.

“We have instituted a number of intentional programs to diversify the workforce among all underrepresented minorities,” says Nolan Atkinson, Philadelphia’s Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, (a new position created by Mayor Jim Kenney’s administration). “This a process where you’re not going to see the result of your efforts within six months, a year, or even longer. But over a period, our hope is through the mayor’s term of office; we will begin to see changes.”

A $10,000 pay gap between the average white worker and the average worker of color remains unchanged since last year’s report, the first in the city’s history.

The pay gap is attributed in part to the overrepresentation of whites in senior positions and a nine percent gap in salaries between whites and people of color in a small number of “non-executive professional” jobs outside the civil service corps. Civil service rules apply to 95 percent of city workers ranging from janitors and sanitation workers to traffic engineers and grant writers.

The administration’s efforts to reduce pay disparities and encourage diversity are focused on the 1,500 non-civil service positions, 49 percent of which are held by whites. Departmental heads are overwhelmingly white, as is the Mayor’s Cabinet, the report notes.

“City officials are now being asked to prioritize addressing pay disparity when requesting salary increases for exempt employees, especially in categories and positions where large pay gaps exist,” the report reads. “There is an additional evaluation underway of specific jobs in the City’s departments with the largest number of exempt employees.”

Since Kenney introduced the report last year, the representation numbers have slightly improved, with both the Hispanic and Asian workforces inching upwards.

Tuesday’s report finds that 50.45 percent of the city’s workforce identifies as African-American, compared to 44 percent of the population. Many agencies split evenly between a representation of black and white workers, with other racial groups represented to varying, but usually small, degrees. The Department of Licenses and Inspections, for example, is comprised of 170 black workers, 140 whites, 22 Hispanics and 16 Asians. The gender split is 230 men to 126 women.

Women constitute a majority of the workforce in every agency that deals with health and human services, while men make up are the majority in all of the city’s public safety agencies. Every department dealing with transportation and infrastructure operates with a majority male staff as well.

There are a variety of large agencies where the preponderance of the staff are black, including the Department of Revenue, the Department of Commerce, the Department of Parks and Recreation, and the Department of Prisons. Majority white agencies include the Fire Department, the Police Department, and the Law Department.

The City Planning Commission and the Historical Commission are both predominantly white, reflecting longtime diversity issues in the planning and architecture fields. According to recent estimates, over 80 percent of the planning profession is white, and among architects, the chasm appears to be even wider.

At public meetings, the lack of diversity can provoke distrust, especially in segregated African-American communities. PlanPhilly reporters witnessed this wariness at civic engagement meetings in West Philadelphia last year, where Philadelphians periodically questioned city staffers about racial disparities between planners and the public.

The report examines the application trends to the Civil Service workforce, which includes the vast majority of Philadelphia’s municipal workers. Many of the applicants didn’t disclose gender or race, but the majority of those who did identified as respectively, men and African-American. Administration efforts to diversify the municipal workforce have not yet focused on the ranks of the civil service, primarily because of legal hurdles.

“The civil service workforce is a much larger project,” said Atkinson. “We are very much committed to bringing about intentional change in that area, but we start with our focus in addressing issues in the exempt workforce because you aren’t dealing with civil service examinations or regulations.”

This won’t be the season’s last analysis of the municipal bureaucracy. Pew Charitable Trusts is working on a comparative study about Philadelphia’s city government hiring practices. It is expected to be released later this winter. Atkinson says the city wants to analyze that report before making any civil service reforms.

The next report may include a few revisions as there appear to be some discrepancies between the city report and the actual composition of some agency workforces.

The Historical Commission, for example, is reported as having five male workers and two female workers as of June 30, 2017. But at that time the agency only had a staff of five, by this reporter’s recollection, and three of their planners were women.

The staffing numbers for the Planning Commission and the Office of Transportation & Infrastructure Systems appear to be off as well. The Division of Housing and Community Development, meanwhile, is a subgroup of the Department of Planning and Development but is listed separately. It also has far more than the ten employees numbered in the report. (The press representative for these agencies did not return queries about staffing numbers by Tuesday evening.)

Atkinson says that the numbers may be inaccurate because they only include data that people voluntarily share with the city. He hopes to correct such inaccuracies in future by having department heads submit monthly reports on staffing diversity numbers, which departmental human resources officers will then fact check.

“There may be some numbers foul-ups because someone or a group of people may not have disclosed [their race or gender],” said Atkinson. “The other explanation is that we made a mistake.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.