Found in South Philadelphia, an Underground Railroad station

From the outside, 625 South Delhi Street looks like an average Philadelphia rowhouse. But in the 1850s, it was home to Underground Railroad leaders William and Letitia Still.

Listen 2:04

The William & Letitia Still House at 625 South Delhi Street. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From the outside, 625 South Delhi Street looks like an average Philadelphia rowhouse.

But in the 1850s, it was home to Underground Railroad leaders William and Letitia Still. Within the house’s narrow confines, they hid hundreds of escapees and gave well-known figures like Harriet Tubman shelter.

Looking at this almost 180-year-old rowhouse just off South Street, preservation activist Oscar Beisert says that its stoop appears to be the original marble from the 19th century.

“We don’t even have basic African-American landmarks protected in Philadelphia…[so] finding that stoop where she [Tubman] potentially arrived with people from Maryland, that’s what I think is really incredible about what we have here,” said Beisert.

On Friday, Beisert and preservationist James Duffin successfully argued that the house deserves a place on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. The designation — unanimously supported by the Philadelphia Historical Commission — means that the structure can’t be demolished or significantly altered unless the commission grants an exemption to the property owner.

The house is owned by an entity called F&J Homes LLC, which acquired it last year. They did not contest the nomination.

The campaign to protect the house featured an unusual amount of backing from experts outside of Philadelphia, including Columbia University Professor of History Eric Foner and Lonnie G. Bunch III, the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History.

“In the current cultural moment, Americans are reassessing which historical figures and events are worthy of public remembrance and commemoration,” wrote Bunch in a letter supporting Duffin and Beisert. “In this context, the extraordinary movements in which Still was engaged are becoming increasingly visible and essential elements of a renewed national story.”

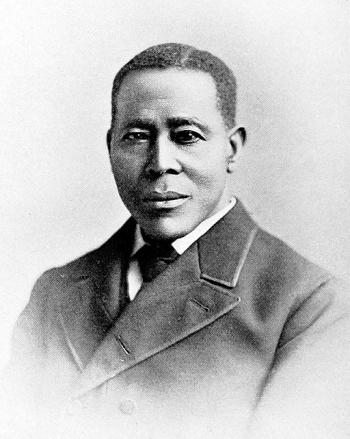

The story that the advocates use to bolster their case focuses on William Still, who moved to Philadelphia in 1844 and later began working for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.

As the chairman of the organization’s Vigilance Committee, he orchestrated Underground Railroad activities in Philadelphia and across the country. One historian described him as “second only to Harriet Tubman in Underground Railroad operations.” Between 1850 and 1855, in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act — which required that Northern states assist in capturing escaped slaves — Still and his wife Letitia sheltered hundreds of escapees in their home.

In one case cited in the preservationists’ brief, Still rescued a woman and her two sons from enslavement within sight of the white Southerner claiming ownership. The encounter happened as the party was about to cross from Philadelphia to Camden on the ferry. African-American dock workers barred the white Southerner from making contact with the family while Still and an accomplice spirited them back into the city. The case made national news when Still and his allies were arrested. The story was eventually novelized as The Price of a Child.

In a rendering contained in the brief, Still is shown lifting the lid of a three-foot-long, two-and-a-half foot deep, and two-foot-wide box. The box held a man: Henry “Box” Brown, who mailed himself from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia to escape slavery.

“Some images have Frederick Douglass lifting the lid of the box,” said Duffin. “But that’s just because everyone knew who he was. Douglass actually wasn’t in Philadelphia at that time. It was Still.”

Still is also renowned for writing one of the only firsthand African-American penned accounts of the movement, titled simply, The Underground Railroad. It is 800 pages long and includes dozens of individual tales of escape. (“It was, in essence, the first African-American encyclopedia,” writes Joe Lockard, professor of English at Arizona State University and founder of the Anti-Slavery Literature Project.)

Many prominent historians like Foner and Lockard wrote letters to the Historical Commission in support of the nomination. They uniformly praised the advocates’ scholarship, noting that many properties supposedly connected to the railroad do not hold up to scrutiny. But they found Duffin’s scholarship impeccable.

Duffin discovered the house by poring over city records, cross-referencing the address with maps, and advertisements for Letitia’s business in abolitionist newspapers from the 1850s.

Many of the historians emphasized the house’s importance in the context of the national debate about Confederate monuments, and which aspects of United States history to commemorate.

Foner, for one, said he wants to see more symbols of emancipation and black history elevated rather than simply having the Confederate statues torn down.

“Personally, I prefer to add new historic sites to make the representation of history more accurately reflect our diverse past and present,” writes Foner, author of Gateway to Freedom, “and to honor those who fought against slavery as well as those who went to war to defend it. Thus, designating the Still home as a historic property would be a statement… about what in our past we choose to honor and why.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.