Grays Ferry’s long-closed Lanier Playground reopens, with new hope and new purpose

Located in the heart of Grays Ferry, Lanier Playground had been closed since 05, but memories of when it brimmed with activity stayed alive in longtime neighborhood residents

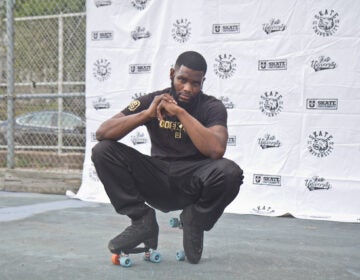

Youngsters try out the new swings at Lanier Playground during a tour in advance of its official reopening. Malcolm Burnley/PlanPhilly)

This story originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

Located in the heart of Grays Ferry, Lanier Playground had been closed since 2005, but memories of when it brimmed with activity stayed alive in longtime neighborhood residents. You’d hear stories about the softball leagues that used to play deep into the night here, the handball tournaments, the annual “summer Olympics” that wooed local kids. It was not uncommon to see spectators overwhelming the sidewalks just outside the chain-link borders, they recalled.

Between the throngs of people and a police station that formerly sat across the street, the convivality felt well protected for some, yet cordoned off for others, long before the playground was shuttered. Many Grays Ferry lifers remember the large 3-acre lot of Lanier differently, less for camaraderie and more for violence and racial exclusivity.

“We couldn’t play here, because there was lots of racial tension” said Norman Best, who is black and has lived in Grays Ferry for more than 60 years. “You couldn’t really go over here, because the police station kept the neighborhood divided. And if you did go over here, you had to fight.”

With last weekend’s grand reopening of Lanier, a milestone that capped off nearly five years of planning and construction, many in the community are hoping that the playground’s complicated and contentious history is part of its past, not its present and its future.

“We need a change,” said Best. “Not just this effort, but the entire Grays Ferry community.”

There’s reason to be optimistic: Not only has the park changed dramatically on the surface, its literal foundation has transformed as well, a symbol for the kind of holistic change that Best would like to see writ large. Below ground, covered over by a new baseball field, lies one of the most ambitious examples of green infrastructure in Philadelphia. Through the Green City, Clean Waters initiative — a citywide effort to reduce stormwater pollution — the Philadelphia Water Department has installed at Lanier a water-filtration system that will manage up to 106 million gallons of water per year in the neighborhood. It’s the largest stormwater basin in the city, according to the Water Department.

“It’s massive in terms of reducing the impact of stormwater runoff in the area,” said Tiffany Ledesma, team manager for public engagement at the Water Department. “There will be that much less water flowing into the sewer system.”

Though the stormwater basin was the centerpiece of the renovations at Lanier, its installation prompted a broader reimagining of the playground that brought together a coalition of community and governmental partners, including the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation; the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, which contributed a $350,000 grant; and Parks for People, a citywide initiative run by the Trust for Public Land that has the goal of creating accessible green spaces within a 10-minute walking distance of every home in the city. Lanier is the fifth renovation completed under Parks for People.

A multiyear engagement strategy led by the Trust for Public Land brought together subsets of Grays Ferry that had historically viewed Lanier as a flashpoint of racial disharmony.

The long absence of activity allowed “both sides of the gate” to reconsider their views on the park, said Brian Clinton, president of Friends of Lanier. “The white residents had ownership of the park for a long time,” he said. “[Lanier] was the border in between the two neighborhoods” — white and black — “which were smack up against each other, with the playground in between.”

Grays Ferry remained a persistent locus of racial conflict in Philadelphia long after the days of Frank Rizzo parading into the neighborhood with his nightstick and cummerbund. In 1997, a black teenager named Raheem Williams was brutally attacked in Grays Ferry by a group of white adults who had been drinking at a party, which sparked retaliatory violence and renewed mistrust among factions within the neighborhood. Minister Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam, marched through Grays Ferry with thousands of people in protest.

Naturally, old wounds flared up in discussions about the new-look Lanier. But the organizers didn’t try to peg a process of generational healing on community engagement surrounding one playground.

“We knew there was past tension in the community,” said Gretchen Trefny, manager of Parks for People Philadelphia with the Trust for Public Land. “We didn’t want to lead with that [tension]. We wanted to look toward the future. So, instead of asking people what they wanted in the park, we asked them to provide their vision for the park. Once we were able to show people who thought they might not get along that the majority of people had the same vision — they wanted a safe space, a place to walk and recreate — then the relationships improved.”

“I think the passion of seeing something positive happen in Grays Ferry overtook any conversation about race relations,” said Kyle Shenandoah, vice president of the Grays Ferry Civic Association and a member of Friends of Lanier.

One of the first engagement sessions drew upwards of 80 people. The momentum carried over into the makings of an active friends group, which has met twice a month since April. “We’ve had 30 people come out every two weeks,” Trefny said.

The final design of the park drew heavily on the input from residents. Security cameras and brand-new lighting were included to assuage concerns about safety. Access and visibility have improved by virtue of the fences being lowered to 4 feet, along with creation of four different entrance points to the park. There’s a sprayground and swings for younger kids, plus separate apparatus for teenagers. Recreational equipment exists for adults, too, including kettlebell machines and a “unity path” for walking and running that snakes throughout the park.

Even the building of dual dog parks — one for small dogs, another for all sizes — came out of open meetings with the community. Disrepair after Lanier was shuttered in 2005 — a decision made by the city Parks and Recreation Department because of declining use and budgetary cuts — had rendered the place an unregulated dog park, full of litter and animal waste.

“People are very excited about the dog park, something that I didn’t expect,” said Shenandoah. “We can’t always look for the city to do it; sometimes, you need creative solutions to neighborhood issues, and I think a dog park is a creative solution.”

Saturday’s ribbon-cutting was the official start of a significant upgrade for public space in Grays Ferry, soon to be followed by renovations at nearby Vare Recreation Center, which has been selected as the first site to receive money from Rebuild, Mayor Jim Kenney’s massive capital-improvement plan.

“Lanier Playground is now a safe, quality play and exercise space for all members of the community. I’m very proud of the neighbors around Lanier and the serious effort to have an inclusive community-engagement process over the last three years,” Councilman Kenyatta Johnson said in a statement. “Hopefully, we can use key learnings from Lanier as we begin the process of rebuilding Vare Rec Center too.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.