City Hall is uniting around a lead poisoning law hated by landlords

City Councilmember Blondell Reynolds Brown said the issues delaying a vote on a controversial regulation have been resolved. Landlords aren’t happy.

City Council member Blondell Reynolds Brown advocates for her bill requiring universal lead checks for rental units at a June 6, 2019 press conference. (David Kim)

This article originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

A law designed to strengthen the city’s safeguards against lead poisoning should soon finally get the vote backers have waited for after almost two years.

The bill, which would require all rental units built before 1978 to be free of lead hazards, was set for a vote in June before council let out for the summer. Advocates expected a win. The bill had been in discussion for 18 months.

That idea inexplicably died when City Councilmember Blondell Reynolds Brown suddenly pulled the bill off the council agenda.

She said she had learned of a new “wrinkle” that needed to be discussed.

“Dialogue was still needed regarding the implementation around compliance and enforcement of the pending lead bill,” Reynolds Brown wrote in an email.

That wrinkle appears resolved after a meeting with people she described as the bill’s “stakeholders” including landlords, tenants, city officials and advocates for children met in her office Wednesday.

The goal, she said, was to “achieve a common understanding” of the city department systems responsible for enforcement.

Following the meeting, Reynolds Brown said her office is considering amendments, and that there will be a final vote in the fall. If passed, the bill will take effect on July 1, 2020.

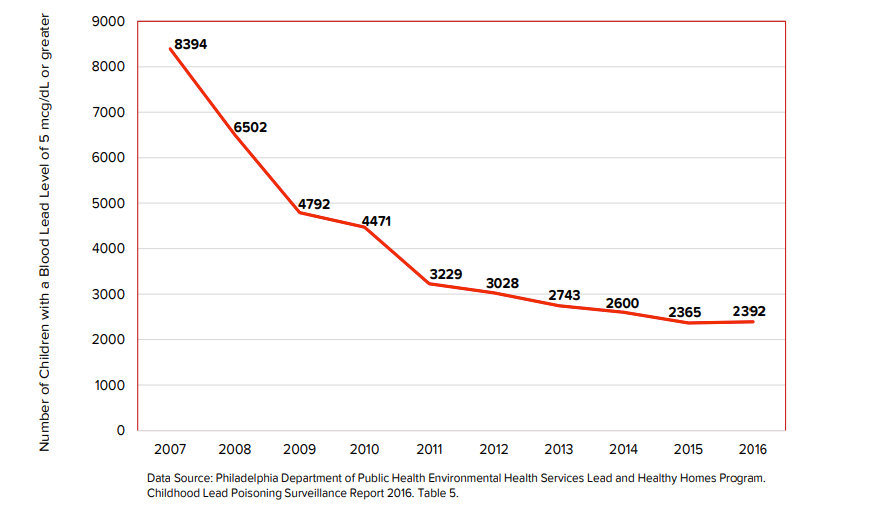

Landlords still oppose the new regulation. They said there’s no need for another law that would increase the costs for landlords. According to city data, the number of children with blood lead levels above the city’s threshold for danger fell from 1,413 in 2006 to 369 in 2015.

“What we’re doing is working, let it continue to work,” said Victor Pinckney, from the Homeowners Association of Philadelphia (HAPCO).

Lead can cause brain damage, learning, and behavior problems, such as reduced IQ and juvenile delinquency, hearing, and speech problems, and delays in growth and development. No amount of lead is safe according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Enforcing ‘universal lead disclosure’

The new lead bill requires landlords to certify all housing built before 1978 is free of lead hazards before obtaining or renewing the rental license required to collect rent.

The current lead law only requires certification on housing built before commercial lead paint was outlawed in 1978 for units with tenants that report children under 6 years old in the home.

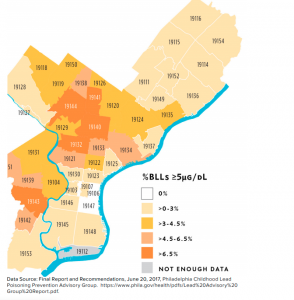

According to city data, only about one quarter of the estimated 22,000 rental units housing children of those ages are in compliance with the regulation. About 2,000 kids are lead poisoned every year in Philadelphia, according to the Health Department. Sixty percent of them live in rental units.

Health Commissioner Thomas Farley and L&I Commissioner David Perri both support the new regulation, known as universal lead disclosure. The officials emphasized in presentations that the city has the systems in place to enforce the regulation.

“The current law is very difficult to enforce because it applies only to rental properties with young children in them and the health department does not know where these children live,” Farley said. “The city would be in a much stronger position to enforce the proposed law because it applies to all rental properties and the certification requirement would be tied to a renewal of the rental license.”

The city would ensure compliance through linking the Philadelphia’s Health Department, which collects the certificates, to the city’s License and Inspections database. That way, a rental license would automatically be denied if the system did not find a lead certificate for the unit — just like when the system finds tax delinquency or code violations.

Farley also showed estimates of the costs of certificating and remediating units to protect children from lead hazards.

According to Farley’s presentation, lead-safe certifications, which guarantee that even if there might be lead in the unit it’s been contained safely, cost about $150. Lead-free certifications, which prove there’s no lead in the unit, go up to $350, he said.

If the unit has lead, landlords can’t rent out until they remediate, which involves wet-sanding the existing paint and applying a fresh coat of lead-free paint.

Why landlords oppose the bill

Landlord representatives, such as the HAPCO argued the extra cost will put low-income landlords out of business. But the Health Department estimates the job, which would be required in about 25% of rental units and would take in average of three days, will cost no more than $1,500 per unit.

HAPCO’s Pinckney said that’s still too much money for a low-income landlord.

“Landlords could greatly reduce these costs by having their own staff trained to do the work,” Farley wrote in an email.

The health department offers training for a dust wipe technician to do lead-safe certifications for $150 and a five-day instruction for a certified risk assessor to do lead-free certifications for $700.

Reynolds Brown and backers of her bill argue the new bill offers several layers of protection against lead. They say all rental units should be certified free of lead dangers because kids move and spend time in other houses. Having the certification apply only to landlords renting to families with small children also creates an incentive for discrimination, they say.

Ruth Anne Gordon, president of the Green Healthy Homes Initiative in Baltimore, attended Reynolds Brown’s meeting. The Maryland city reduced lead poisoning in children by over 90% through legislation similar to the bill proposed in Philadelphia. Gordon said the law did not increase rents or put landlords out of business.

George Gould, a senior attorney at Community Legal Services, said the issues covered in the meeting were discussed during a council hearing in March.

“Quite frankly, we were obviously frustrated and disappointed that the bill did not run in June and I’m not sure we really had to have this meeting,” Gould said. “But we had it and I thought it ended up being productive. Everybody was on the same page, except for the landlords, and the councilwoman said she was prepared to move ahead.”

Colleen McCauley, health policy director for Public Citizens for Children and Youth, said the Lead Free Philly Coalition hopes Reynolds Brown will put the bill up for a vote in September.

“I wish that we had a final vote back in June,” she said. “Wednesday’s meeting with all the stakeholders really gives me great hope that we’ll move forward with this bill as early as possible in the fall and we can get to the business of better protecting children.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.