Walking Market Street with Jan Gehl

Cities should be for everyone.

Cities should make people healthy and happy.

Cities should be designed to respond to human nature and needs.

What would a designer who has based his career on those principles make of a Philadelphia street?

I put that question to superstar Danish urbanist Jan Gehl when I invited him for a walk down Market Street from Old City to City Hall in late February.

Gehl’s work, which marries humanistic design with social psychology, has profoundly reshaped cities and our thinking about them. By taking people as the fundamental unit of urban planning, Gehl’s work has helped cities become less auto-centric and focus on creating places that cultivate public life.

Over his 50-year career, Gehl has spread that gospel across the globe, making cities like his hometown of Copenhagen laboratories of livability, well-being, and inclusion. Closer to home his firm worked to help New York City pedestrianize Times Square and make Broadway more bike-friendly, and in Philadelphia has consulted for University City District.

Gehl was in town last month to accept the 2016 Edmund N. Bacon Prize. Fresh off a flight, I met him at the corner of 2nd and Market for our walk, a sidewalk-level view of good, bad, and ugly Philly urbanism. Hoping to see this familiar corridor through fresh eyes, I wanted to hear what he saw working well and learn what prescriptions he might have to mend weak spots.

Old City: Vitality and Variety

At nearly 80, Gehl is spry and sharp, with a dry wit, dropping nuggets like, “the lazy architect’s answer to density is a skyscraper” as we walked. Pinch me.

We started in Old City because the street life from Front to Fifth streets is in many ways stronger than other parts of Market. What makes it work?

On these blocks there is a varied building stock, lining sidewalks with compact storefronts and human scale buildings from different eras. To Gehl, that variation provides both visual interest and creates a concentration of activity.

Narrow storefronts also engage pedestrians. His firm’s research has found that the ideal storefront width is about 19 feet, which corresponds with roughly four seconds of walking – an ideal interval, he said, to keep the human mind stimulated. He paced out several shops on the 200 block, finding each a little small.

On the 300 block he admired the cluster of buildings associated with Benjamin Franklin, but pointed out a study in contrast across the street: Half the block has a clunky, late-20th century bank building while the other half is packed with narrow, older buildings with first-floor commercial. Each of these conditions, he said, invites very different kinds of street life.

“We found that there is a very precise benefit of having active facades at ground floor,” he said pointing to the smaller storefronts. “If you were to check your Facebook on the phone, it would happen in front of the funny shops, among the other people. If you had to tie your shoelaces, it would happen there. If you have to park your bike, it would happen there. We found that all kinds of activities in street were drawn over to where the activity was and people resisted doing anything in front of the inactive place.”

As we moved westward, we took in the bland office buildings housing Fox29, Business Journal, and Wells Fargo.

“Here you have some very large examples of things which you won’t rejoice about or write postcards about in Philadelphia,” he quipped.

As we passed the National Museum of American Jewish History, Gehl noted that there is certainly a place for larger buildings, mixed in with smaller ones, to create texture instead of blocky monotony.

“It is this mixture of small scale and somewhat bigger scale which makes it rich. If all the ordinary streets also are same scale as the museums and the schools and the town hall, then you start to have what Jane Jacobs referred to as dead. The great American cities gone dead.”

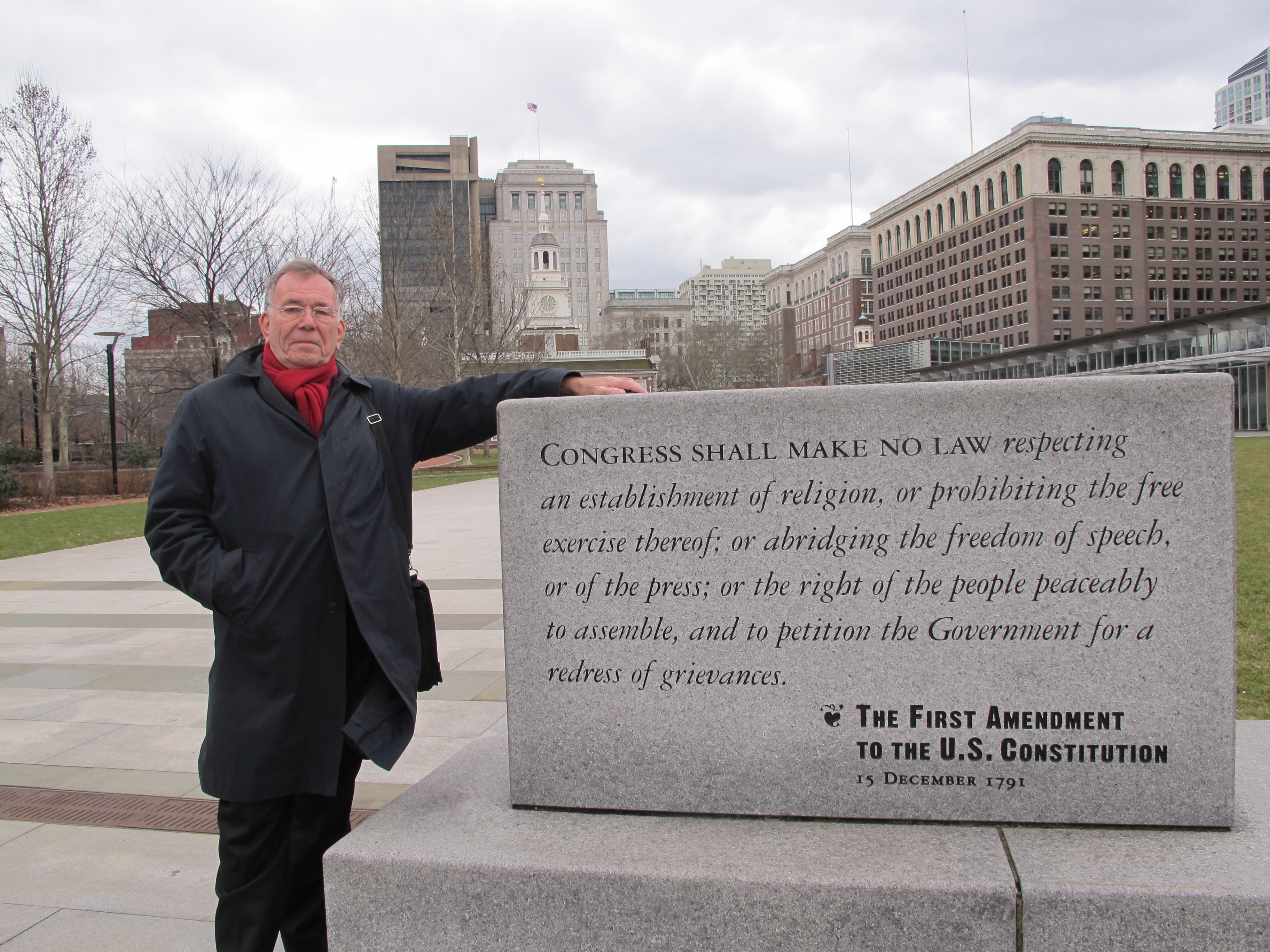

Independence Mall: Planners should defend democracy

At Independence Mall, a transition zone on Market Street, Gehl was taken by the monument to the First Amendment in People’s Plaza – the official free speech corner near 5th and Market.

“I think this is important because I’m very much working for the ‘right for the people to peacefully assemble’ and to ‘petition the government for redress of grievances’,” he said quoting the amendment. “I think that’s very much what urban planning ought to be about in a democracy. I refer to this very, very frequently that in America the First Amendment does say this and in many, many cities you can only exercise this right in the shopping mall, where you cannot actually exercise it.”

In many ways Gehl is an intellectual kindred spirit to Jane Jacobs and Holly Whyte, whose ideas about humanizing cities – from reclaiming streets to creating lively public spaces – have permeated standard planning practice. Fundamentally, they agree, cities are for people.

What’s more democratic than streets and public spaces that give people freedom of choice, of movement, of expression? How far away that sometimes feels.

Market East: Fix Infrastructure, Break Monotony, Be an Engineer for People

West of 6th Street, we entered the long, dreary run of Market East, marked by repetitive large footprint buildings, often with blank, boring, or blocked storefronts.

Amid the taller, blockier buildings the wind picked up – a condition Gehl noted makes people want to move through the area faster instead of lingering. The sidewalk was busy, but he wondered aloud if there was a prison nearby since so many people were wearing badges and tags. Defensive buildings with a security mindset do not tend to contribute to a healthy city street presence.

On the upside, we looked at the East Market and Gallery sites, and Gehl was hopeful about the planned developments, and the promise of improved public life that would come with more variation at the sidewalk level and more storefronts open to the street.

“This is a nice place for wonderful new things to happen,” he said of the ‘Disney Hole’ parking abyss at 8th and Market.

Market Street’s sidewalks also won high marks for their generous width from Gehl, but the corridor’s collection of aging bus shelters did not. We stopped on the 800 block of Market to discuss.

“These are really awful,” he said. “If you go around in Europe you can see a completely new line of bus shelters, which are very light and elegant… Lots of glass and transparency, which is nice also for safety at night and light inside.”

Ours, by contrast, he found to be too heavy, too opaque, and too dated. That can mean a diminished sense of personal comfort and a negative association with public transit. (The new bus shelter designs by Digsau are more in the vein Gehl expressed a preference for.)

Turning around, we checked out an Indego station, and our conversation turned to bike infrastructure.

“I’ve had many discussions with [bike share advocates] who have wanted me to condone the idea that this is very good in the city. My viewpoint really has been that you have to start with building of the bicycle infrastructure and then you can infuse these rental bikes,” Gehl said. Both cyclists and drivers need to get used to sharing the road, he explained. It’s risky to drop cyclists on roads with inadequate facilities.

“I have been very reluctant to think that was a good idea to use [bike share] as ice-breakers for a bike culture.”

In Market Street, though, Gehl saw room for recalibrating street space. He suggested adding protected bike lanes, and shifting travel lanes to ensure a steady flow of buses and cars. That would help make the street’s edges slower so pedestrians and cyclists feel more comfortable. He was amused enough to take a picture of the unintentional protected bike lane at the East Market project, created by Jersey barriers and sidewalk bridging in the bike/bus lane.

To advance this sort of infrastructure change, Gehl’s advice to planners is to think like a traffic engineer — but for people. For decades Gehl and his firm have used data to measure how people use public spaces and why certain public spaces work better than others, with answers often rooted in human senses.

Traffic engineers, he said, know how to optimize roads to serve the needs of cars and drivers. Planners need to do the same things for people, and force politicians to choose whose needs they should answer.

City Hall & Dilworth: Beautiful Imperative

Arriving at City Hall was a relief. We turned around to look down Market Street, back over the ground we’d covered.

“An attractive city is always rated on how attractive it is at eye level. Of course you can say that you are always very attracted [to] the skyline, but you have to be in New Jersey to enjoy it,” Gehl said.

We walked through City Hall courtyard and into a quiet early afternoon at Dilworth. As a Dane, Gehl was happy to see the skating rink attempt to give the park life in wintertime, but he called the rink’s tents “shabby.”

“Very skillful skaters here,” he deadpanned. No one was on the ice.

Of Dilworth Park, Gehl remarked, “It will be gradually more beautiful.”

Coming from him, that’s more of an imperative than a vacant hope. Gehl believes that public places must become more beautiful and inviting. That’s how cities become more livable.

“We have increasing number of tourists and they spend increasing number of time and they have more money. Also our own citizens spend more time. They all have leisure time. They get older, and some of them also gradually have better economy so they can afford a cappuccino from time to time. We can see the general tendency is for cities to be more used. Some say… cyberspace will make public space redundant. We’ve seen not a single trace of it. Think about all of you sitting with an iPhone out in the Sahara Desert, each on a sand dune, having a good life.”

Sounds dreadful, I say.

“You can have water piped into you and fruit and your social life is here,” he said shaking his phone. “Man is a social animal. Actually these gimmicks just have picked up, sort of strengthened our social animalness and we can do more social things in a day than we could have ever before… and much of what’s going on in your cell phone is about arranging where to meet next and telling where you are.”

In other words, place matters. Perhaps now more than ever.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.