Praxis Dialogues: Historic preservation and social justice

On February 28, PennPraxis and PlanPhilly will host the next Praxis Dialogues, the third in a series of public conversations about the notion of “the public good” in design practice. This time we’re focused on historic preservation and our panelists are sharing essays each week leading up to the event. So far we’ve heard from PennPraxis’ Executive Director Randy Mason on preservation and the public good, Penn Law professor and urban scholar (and WHYY board member) Wendell Pritchett on preservation for a changing city, PIDC’s Prema Katari Gupta on preservation as an anchor for the Navy Yard’s redevelopment, and PennDesign professor Aaron Wunsch on Philadelphia’s current preservation climate and what’s at stake. Lastly preservation activist Faye Anderson explores preservation as a form of social justice through her work on All That Philly Jazz.

I am a lifelong activist. While I have loved old buildings as far back as I can remember, I am an accidental preservationist. My aha moment was sparked by the Billie Holiday historical marker, which notes: “In this city, she often lived here.” Here is the Douglass Hotel, which was located at 1409 Lombard Street. In addition to a place to stay, the hotel provided a car service that enabled African Americans to “ride without discrimination or segregation.”

The legendary Showboat was located in the basement of the hotel. Oftentimes with historical markers, there’s no there there. Thankfully, the Douglass Hotel is still there. The building is being reused as the headquarters of a social service agency whose staff told me that when something unexpected happens, they say, “That’s Billie.”

1409 Lombard Street helps tell the story of artistic greats like Lady Day, Ray Charles, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Nina Simone and McCoy Tyner. It also tells the story of disruption and defiance. In remarks to the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said jazz is “triumphant music.” If walls could talk, they would tell how the jazz culture broke down social barriers. The first racially integrated nightspot in Center City was a jazz club, the Downbeat. For the first time, blacks and whites mixed on an equal basis. Jazz musicians created a cultural identity that was “a steppingstone” to the Civil Rights Movement.

At its core, historic preservation is about storytelling. The question then becomes: Who decides what gets saved and whose story gets told? The built environment reflects racial inequalities. Given African Americans’ socioeconomic status, few of the buildings associated with black history meet preservation standards regarding architectural significance. Although unadorned, they are places that tell a more complete American story. The stories of faith, resistance, and triumph are relevant to today’s social justice activists.

There are few extant buildings associated with Philadelphia’s jazz history. The handful of buildings in South Philly includes the Royal Theater, which is currently being demolished and the facade reused in new construction. In West Philly, Club 421, CC’s Nightclub and Natalie’s Lounge are standing. In North Philly, the Heritage House (now Freedom Theater) is still there. The storied “Golden Strip,” Columbia Avenue (now Cecil B. Moore Avenue) west of Broad Street, is a wasteland of vacant lots, takeout joints and LEGO-style student housing.

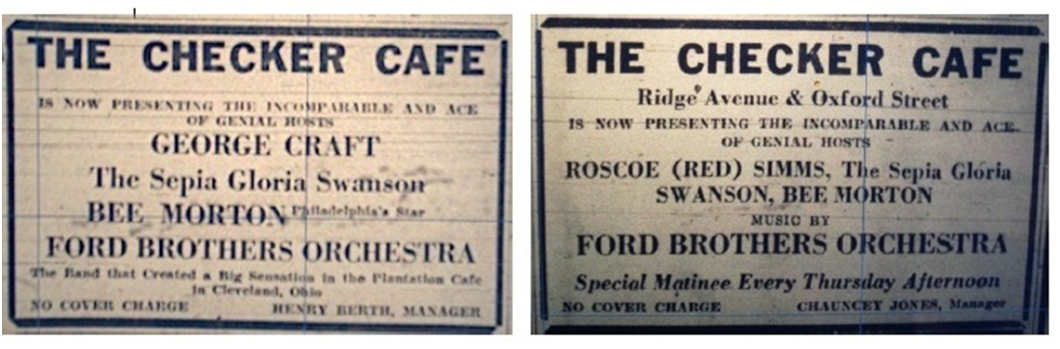

At a meeting to review the potential impact of the proposed Philadelphia Housing Authority headquarters on historic resources, I listened with dismay as PHA outlined plans to demolish 2125 Ridge Avenue. I objected to the demolition in my capacity as a consulting party to the Section 106 review. The 101-year-old building at the corner of Ridge Avenue and Oxford Street was the home of the Checker Café, which opened in 1934.

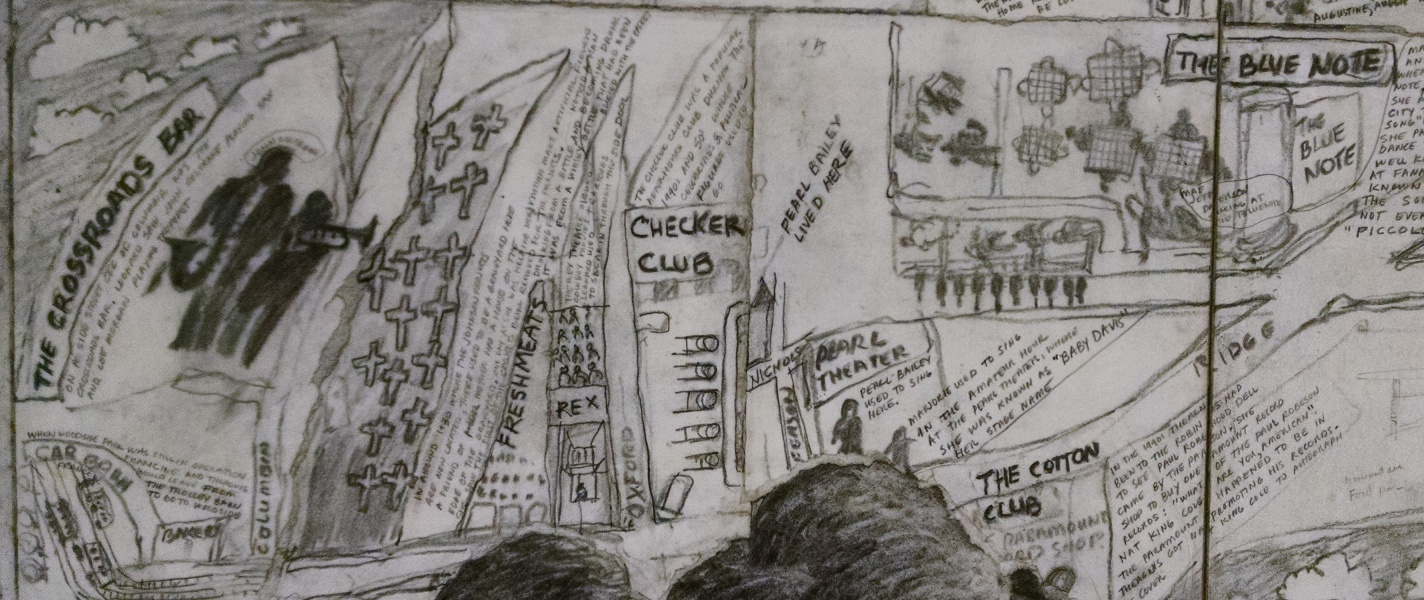

PHA’s proposed office building is in the footprint of the Ridge Avenue entertainment and cultural district, which stretched from 15th Street to Columbia Avenue. In the wake of the Great Migration, the demographics of Sharswood changed. The new residents fueled the growth of commercial operations that catered to African Americans. Ridge Avenue became a safe haven from the indignities of racial segregation. Many of the establishments were listed in The Negro Motorist Green Book that helped African American travelers navigate Jim Crow racial segregation laws in the South and de facto segregation in the North. The 2100 block of Ridge Avenue included the Pearl Theater, Ridge Cotton Club and the Checker Café.

PHA proposed transforming one of the last vestiges of Philadelphia’s jazz heyday into “open space,” i.e., a vacant lot. In the opinion of their consultant, Powers & Company, 2125 Ridge Avenue “lacks significance relating to jazz music history.” I laughed out loud when I read the dismissive characterization of the Checker Café as a “relatively small” venue that provided “good food – good cooks – good service.” One of the servers was a teenage singing waitress named Pearl Bailey. Bailey’s larger-than-life image adorns the iconic storytelling mural, “Ridge on the Rise,” which is on the building’s south-facing wall.

In a letter dated Feb. 16, 2017, Douglas C. McLearen, chief of the Division of Archaeology and Protection, wrote:

It is the opinion of the State Historic Preservation Officer that the Checker Café (2125 Ridge Avenue) is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, under Criterion A, in the areas of Social History/Entertainment. It is clear that North Philadelphia was a center of African American culture throughout much of the twentieth century. The Checker Café appears to be one of a few of the clubs remaining to illustrate the culture and proliferation of Philadelphia jazz.

For me, historic preservation isn’t about brick-and-mortar. The buildings are significant because what happened inside those walls is relevant to current and future generations. It’s about preserving one’s heritage, a cultural public good. Indeed, writer Frantz Fanon observed that if you destroy the culture, you destroy the people.

Historic preservation is about the power of public memory to instill neighborhood pride. To this day, the Checker Café resonates. The New Checker Club sign on 2125 Ridge Avenue connects the past to the present.

Historic preservation must include staking African Americans’ claim to the American story. A nation preserves the things that matter and black history matters. Black history is, after all, American history.

Praxis Dialogues: Preservation and the Public Good will be held at the Philadelphia History Museum on February 28 at 6:30pm. Register here.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.