On Market East, an unusual fight in old battle pitting preservation against progress

By Ashley Hahn

Market Street east of City Hall was one of Philly’s great shopping streets. After years of decline, the tide has shifted, bringing new development to parts of this long-struggling commercial strip. And now an iconic modernist building has been caught in the undertow, in a case that dredges up longstanding questions about the city’s ability to navigate the redevelopment of its unique historic fabric.

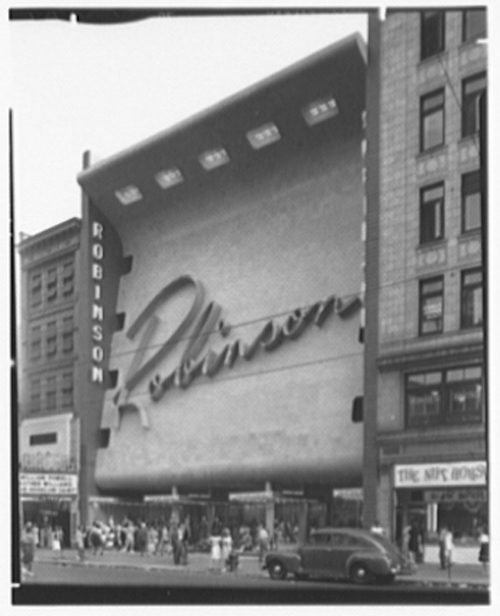

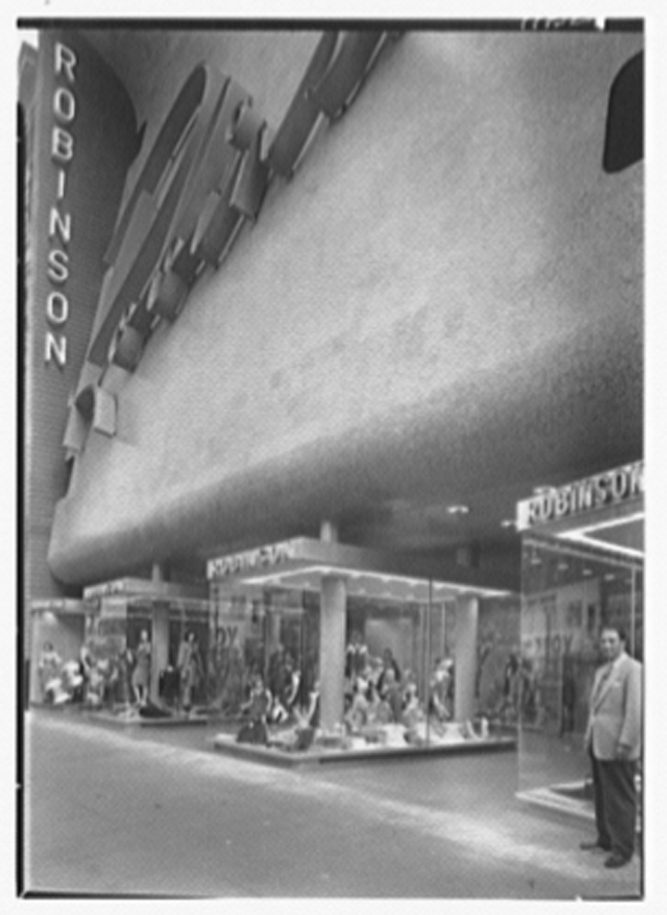

The property at risk is the former Robinson store at 1020 Market Street. The building — most recently home to a cash-for-gold shop, a furniture store, and the Funkomatic electronics store — challenges you to love it. Its façade is a solid wave-like slab rising five stories above Market Street, clad in small purple tiles obscured by decades of grit. Like it or not, it makes an impression. Designed in 1946 by architect Victor Gruen, widely recognized as the inventor of the shopping mall, and his then-wife Elsie Krummeck, the facade is an example of the modernism Gruen brought to commercial design in cities in the U.S. and his native Vienna before turning to the suburbs. The store is the only example of Gruen’s architecture in Philadelphia and a rare survivor among these shops in the country.

In 2016, the city took a step to protect the historically significant architecture by adding it to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. Now that decision has been reversed and the mall developer that owns the building has signaled its desire to put something bigger and newer in its place.

Meanwhile, Philadelphia has been making overtures to repair the fractured relationship between development and preservation, particularly through a new mayoral task force launched last spring. But old tensions die hard, most palpably in Center City where development questions can be exceptionally high stakes and old buildings are too readily viewed as obstacles to growth.

The Philadelphia Historical Commission’s decision to protect Gruen’s edifice prompted an almost immediate appeal by the building’s owners, PREIT and Macerich, the corporate developers behind the redevelopment of The Gallery across the street. PREIT and Macerich opposed the designation arguing that it would create an obstacle to potential redevelopment. They also claimed the building had lost its integrity as an historic resource.

At a 2016 hearing before the Historical Commission, Josh Schrier, PREIT’s vice president for acquisition, explained the purchase of the Robinson building and the two buildings flanking it as merely a “defensive play” to protect its investment across the street. “We bought them because we think we’re going to create significant value at the Gallery,” PREIT chief executive Joseph Coradino told the Inquirer in an interview earlier that year.

The developers’ play itself isn’t surprising, but how it has played out is. The city punted its way through an unconventional appeals process, and ultimately the Department of Planning and Development undermined its own Historical Commission, which had designated the property so recently. In the end, PREIT’s interest in the block was enough for the city to subvert the historic designation.

The episode feels like a disappointingly old school way of Philly doing business.

PREIT and Macerich made their appeal before an unusual special hearing of the city’s Licenses and Inspection (L&I) Review Board during the week of Thanksgiving. The board voted unanimously to strip the Robinson store of its designation, offering no comment at the time or written rationale for its vote. In mid-December, the city decided not to contest the board’s finding, siding with the developers.

“This site is a key to any renaissance of East Market Street, and the City believes that the public’s interest in redevelopment there significantly outweighs the public’s interest in the preservation of the façade,” wrote Anne Fadullon, the city’s director of planning and development, explaining the city’s decision in a letter written in December to Paul Steinke, Executive Director of the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, which sponsored the nomination to designate the building as historic.

In other words, any would-be development on that site, for which there is no public plan, is more important than the building’s historic value.

It’s hard to recall when a city official with direct oversight over preservation matters has so nakedly expressed such a pro-development position influencing a preservation question.

Fadullon did not dispute the building’s significance, which has largely been uncontested by the property owners as well. Although the city defended the designation before the L&I Review Board, Fadullon has now chosen to adopt the owners’ argument that designation is detrimental to the block’s redevelopment potential.

“The building was designated historic, it does have historic merit, but the city has decided, in its wisdom, to vacate that decision in favor of a new, different, larger development possible on that site,” Steinke said. “A lot of historic buildings are not the highest and best use necessarily of the site that they sit on. If that’s the new reality that’s troubling.”

In late December, the Preservation Alliance filed an appeal in the Court of Common Pleas effectively trying to reinstate the Historical Commission’s designation.

One of the biggest points of contention is that the L&I Review Board should never have heard the case at all. That board hears property violations and permit appeals for city agencies, but it is unusual for it to rule on historic designation appeals. In preservation cases, it’s typical for owners to seek relief from a designation by appealing in the Court of Common Pleas or making a hardship appeal before the Historical Commission.

In the case of Robinson, its property owners initially filed their appeal in the Court of Common Pleas. But the court, with the consent of both parties, remanded the case to the L&I Review Board for a de novo hearing – meaning it was allowed to review the nomination from scratch, as though the Historical Commission’s hearings never happened, and ordered to create a new legal record that would be included in the court record. But the board didn’t produce a full record, with elements like a transcript, instead just offering its decision in one word: sustained. The court closed the case.

It’s particularly odd that the city agreed to this process because the Law Department advised in 2016 that the L&I Review Board isn’t the appropriate venue for designation appeals. Court is, and that’s affirmed by well-known case law. And in a practical sense, L&I Review Board members don’t have the same expertise as Historical Commission members who evaluate designations.

City spokesman Paul Chrystie said remanding the case to the L&I Review Board allowed for more time for the city and developers to negotiate. “The City was hoping that a way to preserve the façade as part of a new development could be found, and is disappointed that those discussions were unsuccessful.”

Steinke is more blunt in describing the process.

“The city’s economic development apparatus basically sided with the developer and found a way to get this reheard in front of an audience that turned out to be more sympathetic to the same arguments that were made before the Historical Commission,” he said.

The Historical Commission has broad discretion about what it can factor into its considerations of a nomination, and it did hear economic arguments from the developers even as it voted to designate the Robinson building.

In a larger sense, the case raises legitimate questions about the nature of the Department of Planning and Development’s commitment to historic preservation.

Preservation advocates long have groused that the city will stand up for its historic resources when it is easy. They point to development sites in Center City, like the former Boyd Theatre or the demolitions proposed on Jewelers’ Row, and a host of neighborhood examples. (Chrystie pushes back on this notion, pointing to the very existence of the task force, and city’s defense of the recently designated 81-95 Fairmount Ave, a row of Federal-era houses at the edge of Northern Liberties, in the face of development interest.)

But Fadullon’s contention that the benefits of potential investment “outweighs” those of preservation or reuse is a clear expression of how low preservation ranks in the city’s priorities when it comes to high-value sites.

Her decision to clear a path for wrecking crews gives credence to doubts about the wisdom of nesting the Historical Commission within the new Department of Planning and Development, created through a charter change advanced in 2015. The Robinson case lays bare the exact conflicts of interest feared by preservation advocates when the commission became part of that department – namely that this reorganization, by its very structure, stacks the decks in favor of development interests. How can old things, even those designated historic, ever win when pitted against the Almighty Dollar in this desperate town?

For now, this case serves to remind us that designation alone is no guarantee of creative redevelopment, much less protection. The Historic Preservation Task Force is supposed to make recommendations for policies and incentives that could help ease conflicts like this one. At this point its work isn’t far enough along to influence much. So we don’t yet know how strong the task force’s recommendations will be or how those will be received by the city. Its work could enable the city, armed with new tools, to find the fortitude to stand up for preservation in more development discussions. Will it?

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.