This story originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

Thomas Paine Plaza, the public space outside the Municipal Services Building, is so unremarkable that you’d be forgiven for not knowing its name. But you might recognize it by the bronze statue of former Mayor Frank Rizzo, the plaza’s most controversial resident, or for the giant game pieces scattered throughout the plaza.

The origins of urban public space are deeply tied to the birth of democracy. But poor Thomas Paine, such an influential voice for American independence and democratic values, gets such a disappointing public space. Most days, it is a gray, harsh plaza populated by more public sculptures than people. It is primarily used by office workers on smoke breaks, occasional skateboarders, and people experiencing homelessness, though it lacks basic public comforts like seating or shade. Still, Paine himself might be pleased to see how often this space is used for public rallies and demonstrations within earshot of the city’s halls of power.

Late last month, the City of Philadelphia issued a call for designers to “reinvent Thomas Paine Plaza’s role as a civic space for the present day.” The project will also realize Mayor Jim Kenney’s promise to relocate Rizzo.

The Municipal Services Building and its plaza were built in the same mid-century burst of urban renewal that created the adjacent Dilworth Plaza and JFK Plaza/LOVE Park. Now in their 50s, they’re all getting facelifts. The 2013 Central District Plan proposed unifying these public spaces around City Hall, and this year’s fiscal budget includes $1 million in funding for design costs for Paine Plaza.

Unlike LOVE and Dilworth, where private partners exert some influence over how the space operates, City Hall fully controls what happens at Paine. But the Kenney administration isn’t saying much more about the project than what’s included in the Request for Qualifications, saying it’s simply too early in the process. Despite requests since this spring, the administration ultimately declined to make any officials overseeing the project from the Department of Public Property or Managing Directors Office available for an interview.

Any new design, said city spokesman Paul Chrystie, “will be significantly affected by the structural condition of the plaza. For that reason, an engineering review of the plaza is our first step, and that is what this RFQ is pursuing. Once that process is complete, we can engage the public to explore the potential of the redesigned plaza and how we can unlock that potential.”

In response to questions about how the city defines Paine Plaza’s current identity, its strengths and weaknesses as a public space, and what aspirations officials have for Paine, Chrystie stressed that the city intends to lean on the selected design team to work through questions like that. The RFQ stipulates the selected consultants will coordinate a Percent for Art project and a “public engagement process during course of design appropriate for the plaza’s status as the city’s civic square.”

Though still in the earliest stages, the redesign of Paine Plaza presents an important opportunity to refine the plaza’s role in a constellation of Center City’s revived public spaces. For others, their new identities emphasize leisure, with more seating, food, and even spaces to play. At this point, Paine does more heavy lifting than its neighbors when it comes to supporting free expression.

Paine Plaza was designed not as a place for public life but as part of an urban renewal era composition, attempting to modernize Philadelphia’s civic heart. Its design is inert and hostile to pedestrian life. It is an island, elevated off the sidewalk by granite walls, ringed by a busy moat of traffic, which prevents a natural flow of people passing through to lend it a healthy pulse. That condition is made worse by a sunken canyon on its eastern side, providing access to the city’s service desks at the building’s lower level where people come to get permits. It’s also a haven for individuals experiencing homelessness who are more apt to be chased off from other Center City public spaces. In summer its granite pavers are blazing hot, while in winter it is forlorn and windswept.

It’s tempting to suggest starting over at Paine. But the space serves an important role as a civic stage, an attribute the Kenney administration’s RFQ recognizes in its call for a redesigned plaza to provide “unique opportunities for civic engagement and understand the need for public demonstrations and events.”

Paine Plaza’s bleaker elements – its vastness and lack of landscaping – enable it to hold a crowd. It’s separation from the street gives larger gatherings a sense of enclosure, but its height means it’s not always easy to see public gatherings in progress from the sidewalk. But Paine’s location gives weight to public gatherings regardless of its existing design shortcomings. That role has only become more important since the redesigns of Dilworth and LOVE. The new Dilworth Park doesn’t tend to accommodate protests between its fountain (or skating rink) and a full events calendar. Though demonstrations do spill into and move through Dilworth Park, Center City District says there have been only four permits issued by the city to do so in the last two years. The LOVE Park’s new design was supposed to accommodate public gatherings, but few permits have been requested since it reopened. City Hall’s North Apron is often used for rallies, but its estimated capacity is roughly 800 people, several times less than Paine’s.

Since January 2016, there have been 225 permits issued for public gatherings at Paine Plaza, more than any other individual public space around City Hall. These have included demonstrations during the Democratic National Convention and more presidential visits, rallies about health care and science and protests over the Trump administration’s travel ban and gun violence. There have also been have been protests calling to remove the Rizzo statue. Paine Plaza has also housed several temporary installations of late, exploring immigration, mass incarceration, racial equity, and community food systems. Protest and culture have long been entwined in this spot’s DNA.

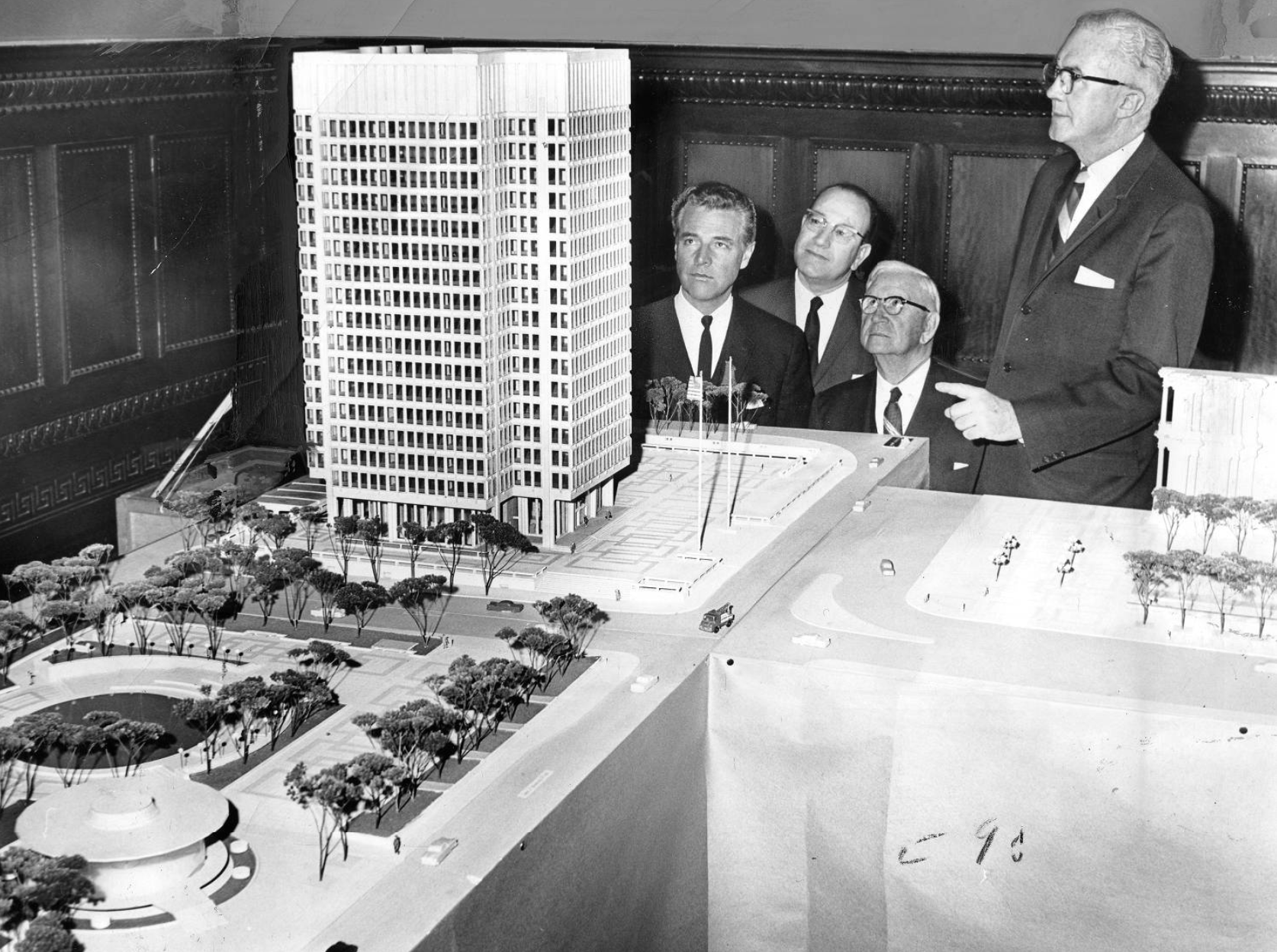

Before the Municipal Services Building was constructed in the early 1960s, this block was known as Reyburn Plaza, a public space where Philadelphians ice skated, protested war, held political rallies, enjoyed concerts, and where city workers often parked. When the new civic building was proposed, some Philadelphians balked at the loss of this public space. Architect Vincent Kling’s design oriented the building on the north side of the block, and the remaining space would be a plaza by the same name. But construction of the Municipal Services Building still prompted demonstrations.

In May 1963, the NAACP picketed the site, protesting police brutality and exclusion of black workers from construction job opportunities at the project. At the rally, the Inquirer reported, NAACP chapter president Cecil B. Moore told the crowd, “In Birmingham they use police dogs, cops, and fire hoses… In Philadelphia, Jim Crow unions deny us the right to work so our children can eat.”

Given this background, it’s even stranger to see the nine-foot-tall statue of Frank Rizzo, who once punched a civil rights protester, looming on the steps facing toward City Hall. But these contested experiences are part of how we collectively define what public spaces mean. And Paine Plaza’s public art has a few lessons we should tune into as well.

The plaza, renamed for Thomas Paine in 1992, is home to strange collection of “plop art” – from earlier attempts to make the vast and downtrodden space more visually interesting. The oversized table game pieces scattered throughout are “Your Move,” by Daniel Martinez, Renee Petropoulis, and Roger White, and installed in 1996. Along the Broad Street sidewalk is a sculpture of young Benjamin Franklin as a printer, by Joseph Brown, installed in 1981. Set in the plaza toward the corner of Broad and JFK Boulevard, is its finest work – a bronze of wrestling humanity called “Government of the People” by Jacques Lipchitz, installed in 1976. Of those on the plaza, the RFQ stipulates the Lipchitz must stay and Rizzo removed.

It’s a strange assemblage, but in its dissonance is a kind of physical expression about the messiness and struggles that democracy demands, which public spaces air out. It’s a place where somehow Rizzo can stand around the corner from Philadelphia’s favorite founding father. Even Lipchitz’s pile of grappling people surrounded by chess and Sorry! pieces can appear like some extended metaphor about the nature of our bipolar politics; some people show up ready to rumble, while others thought it was game night.

When I sat down with Deputy Managing Director Brian Abernathy last year to discuss protest spaces and Paine Plaza’s identity, he acknowledged the space’s importance for public gatherings and pointed to the plaza’s namesake and the “Government of the People” as potent symbols to work with in any redesign.

“That idea of wrestling in democracy is, to me, exactly what the legislative process is. It is what governing is. It is about that battle. It’s about leverage. It’s about how do we move forward as well,” he said of the Lipchitz piece. “That as the backdrop of so many demonstrations is amazing.”

At a moment when there is an enduring appetite for our political exchanges to be taken from the realm of hashtags to marches and rallies in the streets, Paine presents a potent opportunity.

Philadelphia has the rare chance to design a new space for free expression, that thrives through diverse daily uses. The new plaza will need to support healthy public life at the Municipal Services Building, inside and out, while making room for the public to not just occasionally occupy it but co-author its civic identity over time. In other words, no diluted copy of Dilworth Park’s furniture and plantings will do. And it can’t be over-designed or over-managed to the point of dull “animation.”

That makes this project an engineering challenge both physically and socially, but it’s one worth tackling. The city will be smart to choose a design team capable of cultivating a robust public conversation about Paine Plaza, stoking our thinking about what would make for an authentic people’s plaza. The first people I’d want to talk with are those who have pulled the most protest permits to demonstrate and rally there.

Far from a flatlined space, it’s time to concentrate on Paine as a space of high democratic value in the heart of the city. That’s something we all should embrace. As Paine wrote, “Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom, must, like men, undergo the fatigue of supporting it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.