In Eastwick, belief that flooding during Hurricane Floyd was intentional still muddies the water

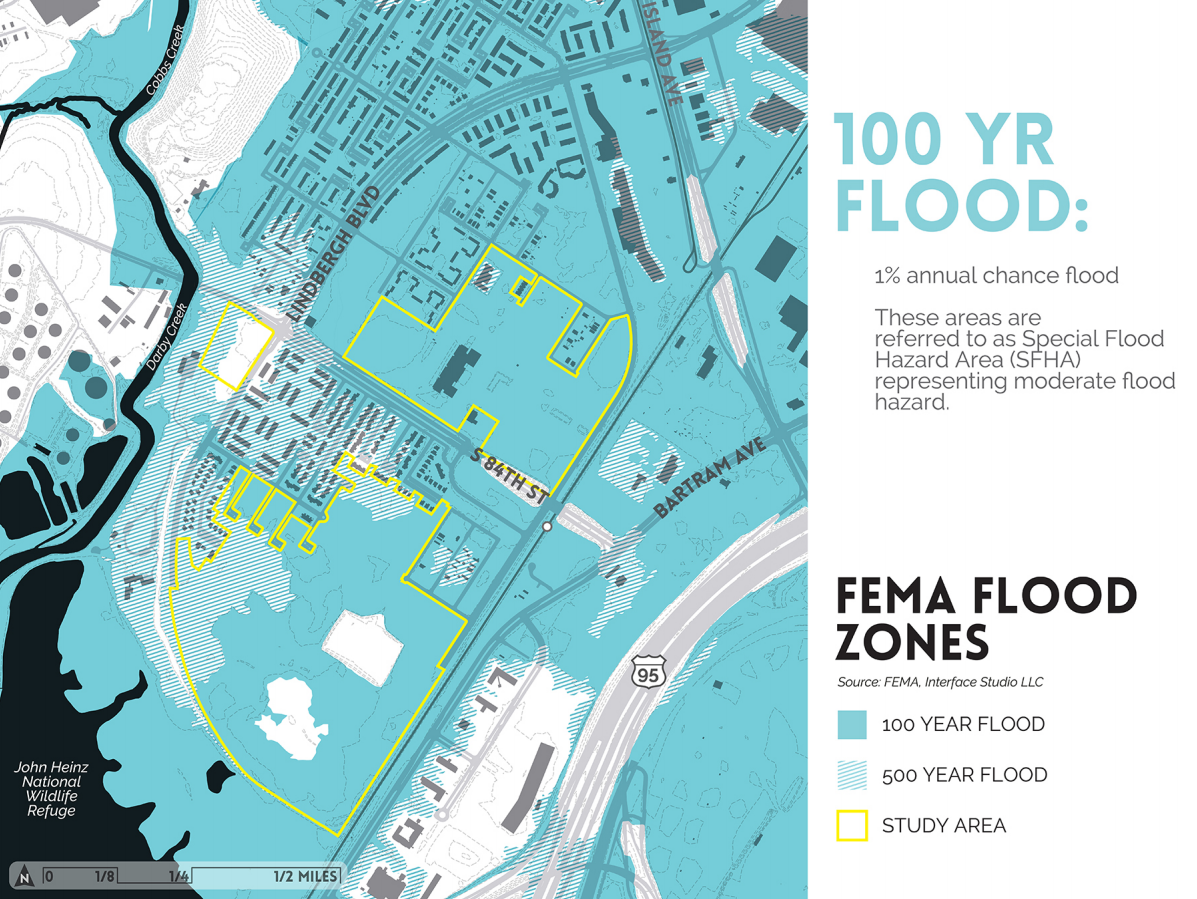

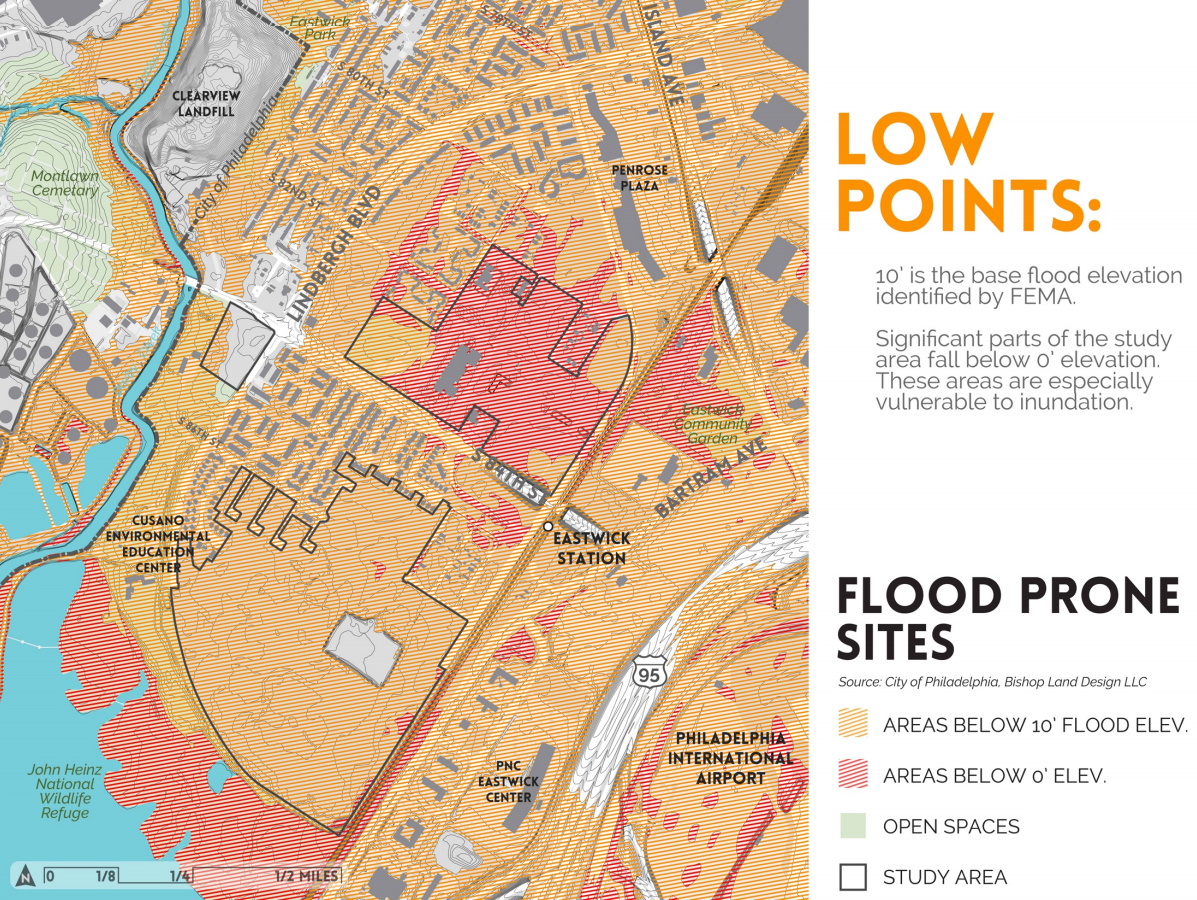

Eastwick residents have long endured regular flooding. The Southwest Philadelphia neighborhood is home to the lowest point in the city. The community sits within the federally-designated floodplain. Historically, Eastwick was a vast marshland, and it’s almost completely surrounded by water: the Cobbs and Darby creeks to the west, Tinicum Marsh to the south, and the Mingo Creek and Schuylkill River to the east. In just the last twenty years, the Philadelphia Water Department estimates that about 130 Eastwick properties have flooded ten times or more.

But members of Eastwick United, a local registered community organization, do not believe the flooding problems are natural.

“We need to dispel that idea that this is a flooding area,” said Darien Thomas, a pastor and member of Eastwick United. The 30-year-old civic group represents about half of Eastwick’s residents.

For the past year, the city has been working with Eastwick residents on a plan to decide the future of 200 acres of publicly-owned land in the neighborhood. In January, Interface Studio was hired as a consultant to draft a feasibility study to find out what can — and should — be done with the land. The city tasked Interface with balancing residents’ desires and market realities, along with the environmental limitations of the waterlogged area.

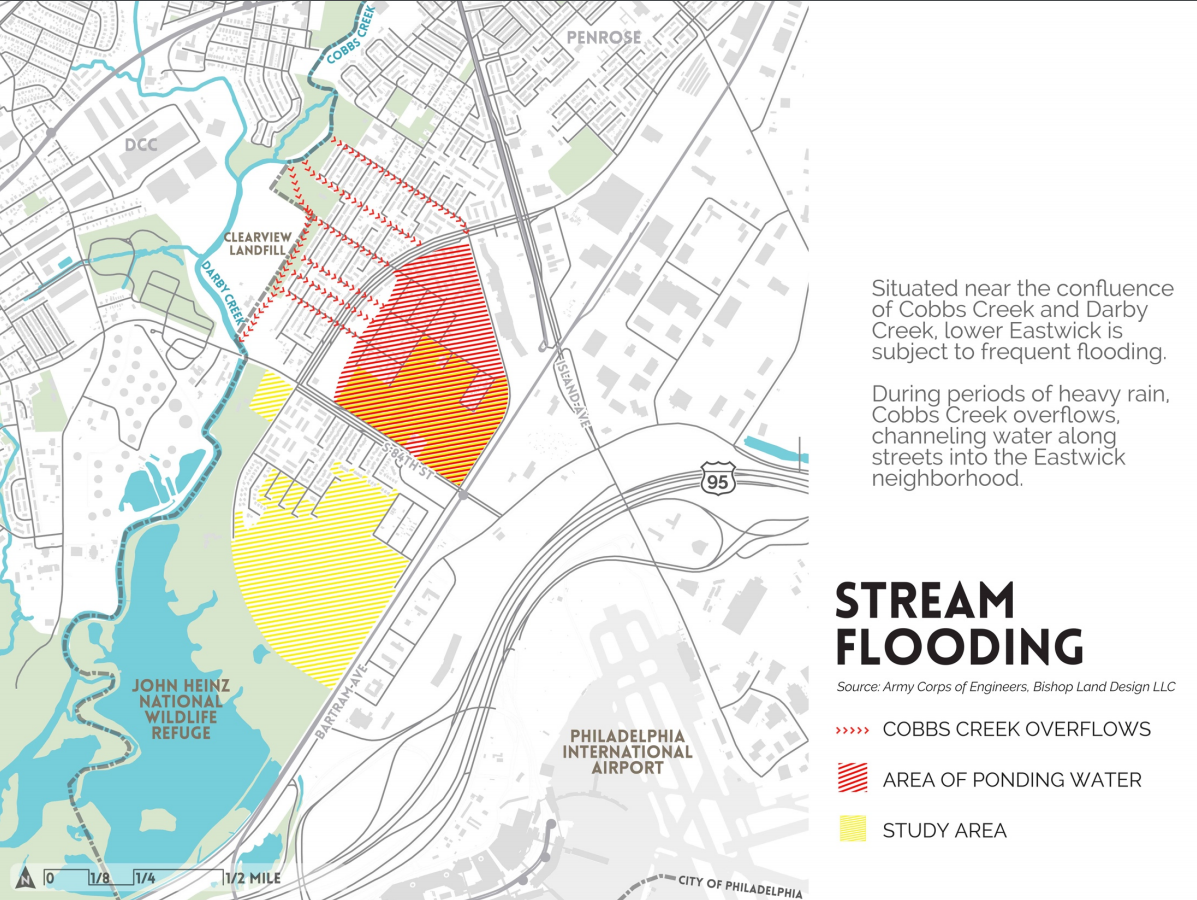

During a heavy storm, rainwater pours into Cobbs and Darby creeks, which flow through Eastwick. There the rivers hit an elevated zone at the former Clearview Landfill, causing water to back up and then spill over the creek banks, flooding an area known as the “planet streets,” where the roads are named after celestial bodies. When the storms are even stronger, the Schuylkill River also pushes groundwater into the neighborhood, and a storm surge comes in from the tidal Delaware River. Experts call this Eastwick’s “quadruple threat.”

But Thomas said that the city shouldn’t make decisions based on Eastwick’s frequent deluges, arguing that only parts of the neighborhood are naturally prone to flooding.

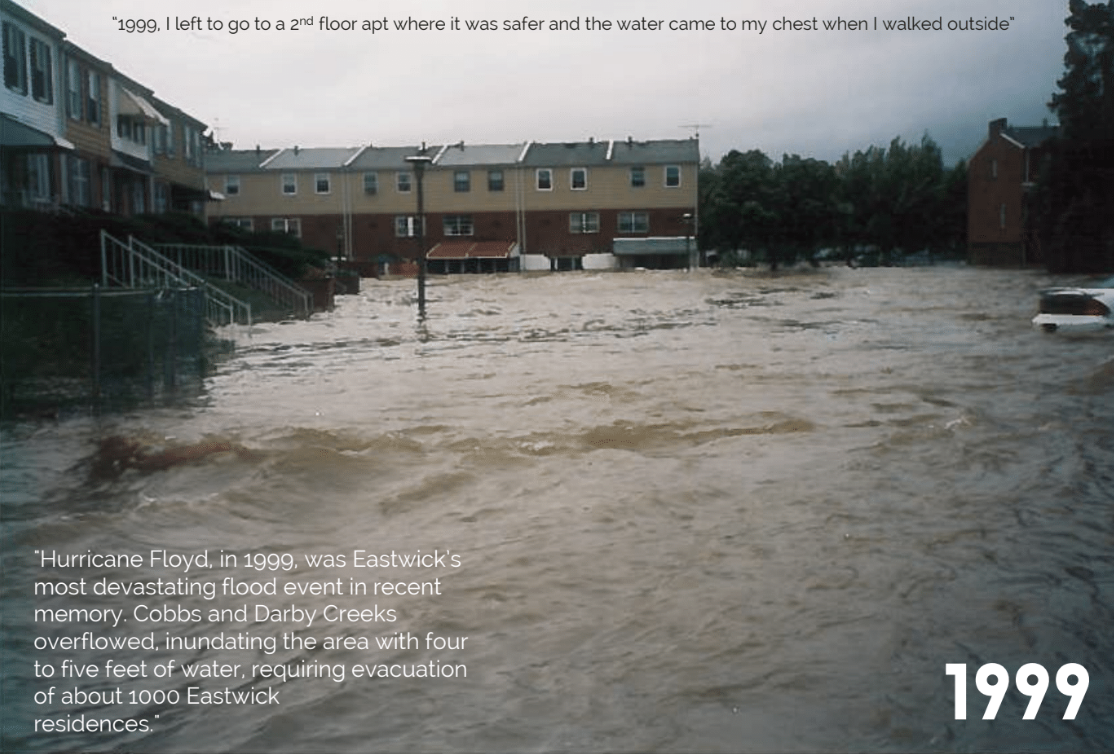

That disbelief in Eastwick’s propensity for inundation stems from when the neighborhood suffered its worst flooding with Hurricane Floyd in 1999. In one day, nearly seven inches of rain fell, a record amount that caused widespread flooding across Southeastern Pennsylvania. In Eastwick, water four feet deep covered the entire neighborhood.

But Hurricane Floyd, Thomas said, “was an unnatural flood.”

Many residents believe Eastwick flooded because water was intentionally released from the Springton Lake Dam, a 3.5 billion gallon reservoir that drains into the Crum Creek in Delaware County. They believe officials wanted to protect Media, a wealthier and whiter suburb.

“Everybody in here knows the flooding didn’t exist,” Eastwick United President Tyrone Beverly said during last month’s public planning meeting at Eastwick’s Penrose Elementary School. “They opened the floodgates and let that water run on top of you.”

Half of the packed gym cheered. The rest — planners, scientists, city officials and members of the neighborhood’s other civic group, Eastwick Friends and Neighbors, which is leading the planning process — rolled their eyes.

“FLOYD WAS DIFFERENT, EVERYBODY KNOWS THAT”

Leo Brundage’s Eastwick home has been flooded eight times since Hurricane Floyd. The block captain and retired ironworker lives in a house he bought in the 1980s on Saturn Place, just 150 feet away from both the Cobbs and Darby Creeks.

Brundage has become an expert in the dynamics of Eastwick flooding. He can accurately recount how Eastwick’s “quadruple threat” causes four to six feet of water to pool on his first floor.

But Hurricane Floyd, Brundage says, was different.

“We got flooded from Hurricane Floyd because of the dam, we all know that,” Brundage said. “If you ask anybody that’s been around here — that was here during Floyd, that came to our meetings — they will tell you.”

Brundage thinks the water was released to protect richer and whiter communities in Delaware County.

“[The Springton Reservoir Dam] was cracking, so they released a million gallons of water at high tide,” Brundage said. “And guess where the water came? This is Media,” he said, pointing up on an imaginary map. Brundage then pointed down. “This is Eastwick. It came down here.”

But official accounts contradict what Brundage, Beverly and Thomas believe.

“Springton Reservoir is really a conspiracy theory kind of thing,” said Chris Crockett, the chief environmental officer with Aqua America, which operates the dam. “There’s no science to back that statement up.”

When Hurricane Floyd hit on the night of September 16th, 1999, Aqua America, then known as Philadelphia Suburban Water Co., issued an alert saying there was a hole in the dam. According to newspaper accounts at the time, the statement led to fears that the dam could break, and forced the overnight evacuation of hundreds of residents along Crum Creek.

But the dam didn’t burst, and, a week later, the company’s president apologized for the false alarm. According to Aqua America, the dam, in fact, prevented more than a billion gallons of water from flowing down Crum Creek.

Springton Reservoir drains into Crum Creek, and the Crum drains into the Delaware River. Crockett, who, until last year, worked with the Philadelphia Water Department for 20 years and has a doctorate in Environmental Engineering from Drexel University, said the flooding during Floyd was caused by the Darby and Cobbs creeks, which are actually in a separate watershed.

“They’re like two different planets,” Crockett said.

Brundage and other neighbors know this. But they continue to believe that water was intentionally released on the night Floyd hit. Their explanation of how the water got into a different watershed, includes water flowing from the Crum Creek into the Delaware River, and then pushed upstream by the high tide into Darby Creek.

The tidal Delaware did back up a lot that night, Crockett said. But, he says it was caused by the hurricane itself, not an intentional release.

“When you look into the volume of water the Delaware River was moving during Hurricane Floyd, which was hundreds of thousands of cubic feet per second, and you look into the flow gauge of Crum Creek, it literally was a drop in the bucket,” Crockett said. “There was no way the Crum Creek contributed in any significant way to the tidal backup. It’s hydraulically and hydrologically not possible.”

Michael Nairn agreed. Nairn is an urban studies professor at the University of Pennsylvania and part of the team working on flood projections for the area.

“If the water was released during the storm surge and tides, it would have flooded the downstream areas of Crum Creek, not Darby Creek,” Nairn said in an email. “Additionally, Crum Creek empties into the Delaware closer to Chester. When you look at the map, it is some distance from the mouth of Darby Creek.”

Crockett added that Media is downstream of the dam, so if the water had been released, that community would have been impacted anyway.

But none of this changes Brundage’s mind. As part of the planning process, environmental engineers have tried explaining to the community several times why their houses flood. But even though he understands their explanations, he doesn’t believe them when it comes to Floyd.

“Listen, they can’t tell me,” Brundage said. “They can give you an academic view — yeah fine, probably the best around — but I’m giving you a true fact. I know exactly what happened.”

Whether the Eastwick flooding was an intentional act or simply a natural tragedy, the fact is, Brundage and his neighbors have reasons not to trust city officials. Brundage’s three-story row home overlooks a beautiful park. Or so you’d think until you get close enough to read the warning signs posted by the Environmental Protection Agency.

“No one knew that this was a toxic landfill until we did research,” Brundage said, looking into bins of documents and newspaper clips he keeps in a closet.

The park, on the Lower Darby Creek Area Superfund site, is a former municipal landfill that operated until the 1970s. In 2006, Brundage got cancer, and so did some of his neighbors. They blamed the former dump, and pushed the EPA to take action. It wasn’t until 2011 that the EPA said the Clearview Landfill’s groundwater and soils presented unacceptable risks to human health. Those toxins flow into residents’ homes every time it floods. Brundage now sits on the Eastwick Lower Darby Creek Area Community Advisory Group, working with the EPA to clean up the site.

That bureaucratic debacle isn’t the first time government has let down the residents of Eastwick.

Like many others in Eastwick, Brundage grew up in the neighborhood. But in 1958, when he was 14 years old, the city forced his family out of the home they owned. Brundage said his family had to hire a lawyer just to get a reasonable amount of money back from the city. They were caught up in an urban renewal project that displaced more than 8,000 residents but was never completed.

“So, how many other black families were in the same situation?” Brundage asks, his voice breaking. “They just took the land.”

Eastwick residents resent seeing all of the community’s schools closed, saying city officials destroyed what was a perfectly integrated neighborhood with churches, theaters, businesses, and everything they needed.

“What I’m seeing now, is no more than what they did back in the 50’s, forcing you [out], taking land,” Brundage said.

At the last public meeting, Interface Studio’s Scott Page said some areas in Eastwick could be developed but others would have to be used to mitigate flooding. Eastwick United members insist officials are using the flooding argument to deny them the kind of development the community wants — schools, parks, playgrounds, community centers, businesses — all so the city can give the land to someone with bigger pockets.

“The lie that we live in a flooded area has kept people back from developing in our community, thinking we can’t develop in that area because it’s a swamp,” said Thomas. “Well, they didn’t say that to the developers who came here years ago and wiped everybody out. And they built.”

“[This] community can’t be rebuilt if the lie is out there,” Thomas said.

Greg Heller, Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority’s executive director, said he understands the distrust.

“We’re talking about decades of history, you’re not going to change it overnight,” he said.

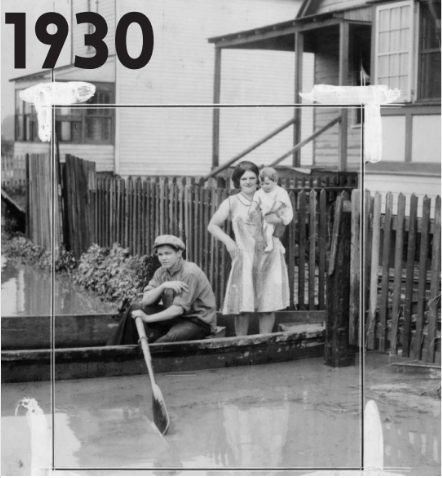

But the city is going to stick with what the feasibility and planning study recommends, Heller said. That may mean no municipal facilities in the flood-prone areas or setting aside undeveloped land to absorb stormwater instead of allowing development. He added that in the last public meeting the consultants showed photos of flooding in Eastwick going back to the 1930s.

“Certainly, the flooding conditions in Eastwick are not a new phenomenon,” Heller said.

Heller said overcoming the neighborhood’s deep distrust will be hard, but he’s committed to “doing the responsible thing” and thinks the process has already been a big step forward in terms of starting to remedy the past urban renewal failures and build trust in the community.

The city, Eastwick Friends and Neighbors, and Eastwick United only have a couple of months left to make compromises and come to an agreement about Eastwick’s future. If the Eastwick United members cannot let go of their strongly-held skepticism over municipal planning processes, then their doubts may end up backfire. The planners may move on without their buy-in or their input, which could further entrench the feelings of distrust and resentment. Judging from the last meeting — where residents disagreed fiercely with one another — there’s still a long way to go.

Mayor Jim Kenney visited Eastwick last month, promising neighbors he would stand for them. That may have helped ease the cynicism in Eastwick. Even Brundage softened his tone.

“Kenney seems to be concerned and assured us that we can count on him. So, only time will tell,” Brundage said. “There’s at least a little hope.”

The next public meeting for the planning process will happen early next year.

Dear reader, your support is essential for PlanPhilly’s independent, watchdog coverage. Please help us continue providing the local public interest news that you value in 2018 by making a tax-deductible donation during our once-a-year membership drive. Thank you for eleven great years of coverage on the built environment and counting!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.