Wharton prof: No amount of money would’ve swung Amazon

Employees walk through a lobby at Amazon's Seattle headquarters. (Elaine Thompson/AP Photo)

This article originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

Hope can blind people to reality, hindsight is always 20-20, and as the dust settles around Philadelphia’s failed bid to woo Amazon, it’s become clear that the city never really had a shot. Still, experts agree that the effort, however, futile, wasn’t in vain.

“I don’t think it’s a surprise,” said Robert Inman, a professor at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. “I think it would have been a bigger surprise if they had gone almost anywhere else, [but] it’s not, in any sense, a black mark against Philadelphia.”

“Philadelphia should feel very good about its presentation to Amazon — being a top 20 finalist has provided enormous branding value for the city,” said John Boyd, a corporate site-selection expert.

As observers noted from the start, Philadelphia’s chances at landing Amazon depended on whether the company’s very public bid process was an honestly open-minded exercise in soliciting cities — or something a bit more strategic.

Many speculated that the headline-friendly competition was designed to elicit larger tax concessions from predetermined favorite locations while generating a massive amount of free publicity. Now that Amazon has picked locations in New York City and just outside Washington, D.C. — as well as a third, smaller operations office in Nashville, Tennessee, a geographically opportune logistics hub — it’s evident that the tech titan placed a premium on the one thing that only a few major U.S. cities can claim: access to large pools of talent in specialized sectors. Philadelphia is not one of them.

Unlike New York, Philadelphia isn’t a global hub for media and finance with an endless supply of Ivy League grads lining up for jobs. Unlike the D.C. region, Philadelphia isn’t a mecca for government and health.

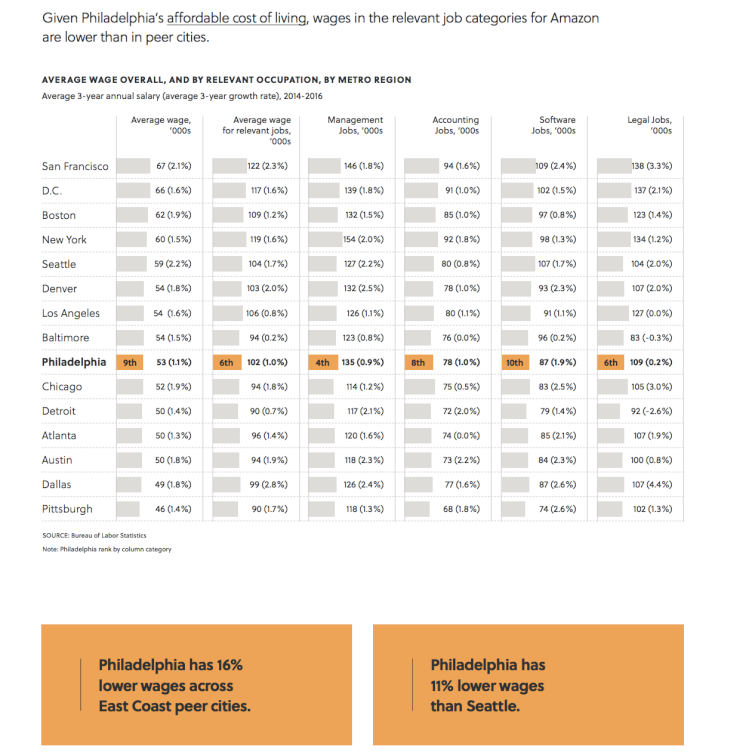

Without the deep bench of talent found elsewhere on the East Coast, Philadelphia, in its 108-page bid, sold itself as a college-packed city with stable growth that’s more affordable and easier to navigate than its booming peers. In its bid, Philadelphia compared a hypothetical Amazon employee earning $100,000 to what the company would have to pay the same employee in other cities to provide the same standard of living: $192,236 in New York City; $125,738 in Washington, D.C.; $124,810 in Boston; and $122,278 in Seattle.

The icing on the just-right, “Golidlocks” cake: an eye-popping $5.7 billion in city and state tax breaks for the internet giant in exchange for the HQ2’s expected $5 billion investment, 50,000 jobs and estimated $6 billion haul in new tax revenue.

Based on those figures, Philadelphia offered Amazon $20,000 per job and Pennsylvania another $94,000, or $114,000 combined.

Some lessons learned

But what Amazon really wants, cities can’t buy with tax breaks or low rent. The company is expanding aggressively into on-demand video and government contracting, which means it needs access to the media industry and government sector. As Amazon hunts for top-tier talent in those areas, it’ll be willing to pay a premium to access deeper pools of potential employees and greater access for potential collaboration with other firms. Amazon is also looking to grow internationally, meaning it will need expansionary capital and political cover. New York City is the financial and media capital of the U.S. And D.C. is the literal capital. No other city could realistically compete.

“There’s no amount of [incentive] money that would have swung the case, I think,” said Inman. “We’re not a city that could have provided what Amazon needed.”

The mostly unredacted bid released by the City of Philadelphia only represents a fraction of the correspondence and documentation the city and its partners — Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation and the state — sent Amazon. Philadelphia spent $160,000 on the initial bid — $100,000 in city funds, and $60,000 came from noncity funds, according to PIDC. After Philadelphia was named a finalist, the industrial development agency spent $300,000 on responding to Amazon’s questions, hosting Amazon officials, and preparing additional marketing materials to woo the company.

City officials said Tuesday there was little they would have changed in Philadelphia’s bid. But for PIDC President John Grady, the HQ2 process signaled a need for the city to expand its economic development strategies. Pointing to the successful growth of Philadelphia’s tourism and hospitality industry — an initiative that began in earnest in the early 1990s under Mayor Ed Rendell’s administration — Grady suggested the city take a similar approach to develop its nascent technology sector.

“This gave us an opportunity to remind ourselves that we need to be as consistent and proactive in promoting Philadelphia as a place to work, as a place to attract and grow talent, and a place to grow businesses,” he said. “I think that’s the real value [of the HQ2 process.]”

In addition to the tax breaks, Philadelphia’s economic development officials agreed that Amazon’s decision to move to New York City and D.C. was driven in large part by talent recruitment. Whereas workers once moved to the company locations, companies increasingly must go where they can find highly educated employee. As certain sectors agglomerate in certain cities, the chain reaction of that clustering will only expand.

That could benefit Philadelphia in two ways.

“If you ask what do we do as a city, and what do we do exceedingly well, it’s medical technology and health care delivery,” said Inman.

At a press conference announcing the HQ2 loss on Tuesday, the city’s business boosters repeatedly referred to advances in genomic research as an area where Philadelphia may produce a home-grown megacorporation like Amazon.

Philadelphia is also well poised to take advantage of changes in what younger, college-educated employees seek in their employment, said John Boyd, a corporate site selection expert.

Factoring in social impact

“Companies are calling us now and asking us to document social impact — that’s never been the case before,” he said.

Milton Friedman’s exhortation that a corporation’s only social responsibility is to increase its profits has fallen out of favor in the business world. While corporations often pursue community service initiatives or donate to good causes as a way of bolstering their brand among consumers, employee recruitment is driving this latest wave of corporate social consciousness. Social impact allows “companies like Amazon [to] attract so-called creative class professionals from around the globe that have myriad other employment options,” Boyd said. “It allows Amazon to be more flexible with benefit packages or salary packages if they can offer some other intrinsic value related to that job that’s attractive to a millennial or creative class young worker.”

More so than prior generations, millennials and their younger siblings in the next generation seek meaningful work, and seek work at organizations they can be proud of. Deloitte, a consultancy, recently surveyed college-educated millennials and Generation Z full-time workers mostly employed in the private sector. Deloitte found that younger educated workers were dubious of private corporations, with 45 percent saying businesses behave unethically — and only 47 percent agreeing that business leaders are committed to helping improve society.

While receiving a college degree once made the holder more likely to be a moderate Republican, college graduates have been breaking heavily for Democrats in recent years, and recent graduates even more so. Combined with the skepticism of large corporations engendered by the 2008 Great Recession that hit just as many millennials were graduating college, companies are realizing they need to differentiate themselves on social issues in order to recruit and retain young, educated employees. These trends may be accelerated by the fact that women make up a majority of college students — 56 percent as of 2017, and growing — and an even larger percentage of graduate students.

Independence Blue Cross CEO, and incoming Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce chairman, Dan Hilferty applauded the Kenney administration’s efforts and pledged to continue working with the mayor “to develop a pro-growth, pro-neighborhood agenda.”

“Because they’re not separate,” Hilferty added. “When you come together, nobody can beat you.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.